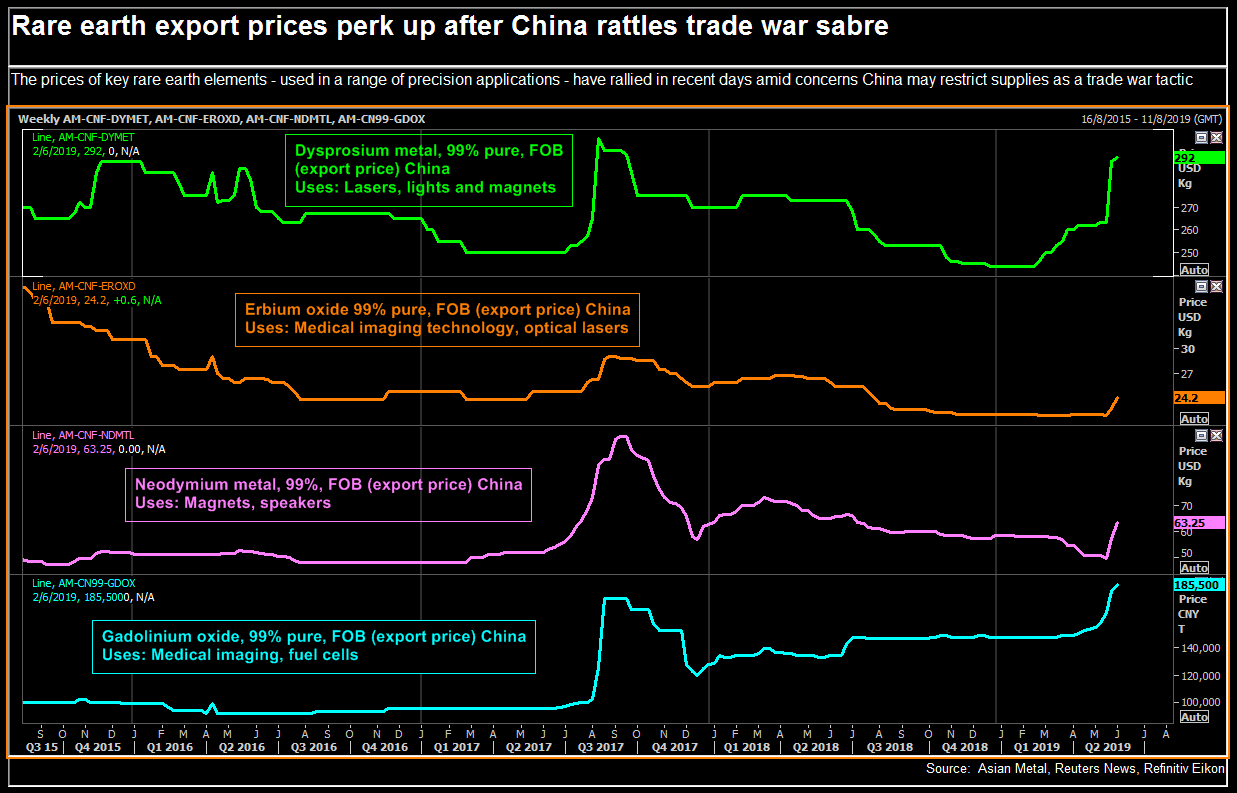

There’s persistent market chatter and media headlines that suggest China might try to leverage their control of rare earths production as a result of a seeming escalation of the trade war with the USA. We’ve seen this before of course, back in 2010 – 2012, when there were fears that China would use its market influence to withhold supply and drive up prices. This proved to be a temporary phenomenon.

History is repeating itself with a host of emerging rare earths plays being promoted to investors. Many of these aren’t in any way ‘new’ and have been around for some time. The bottom-line is that rare earths aren’t ‘rare’, and profits aren’t easy to come by in the rare earths industry. Which is why the West has been happy to outsource its rare earth supply China. Will things really change this time around?

If you haven’t heard, there’s a trade war going on between the US and China. Or more accurately, between the Trump Administration and China, with the US consumer (and the world economy) as the inevitable loser/s. Hostilities of this nature inevitably engender speculation as to what weapons will be deployed.

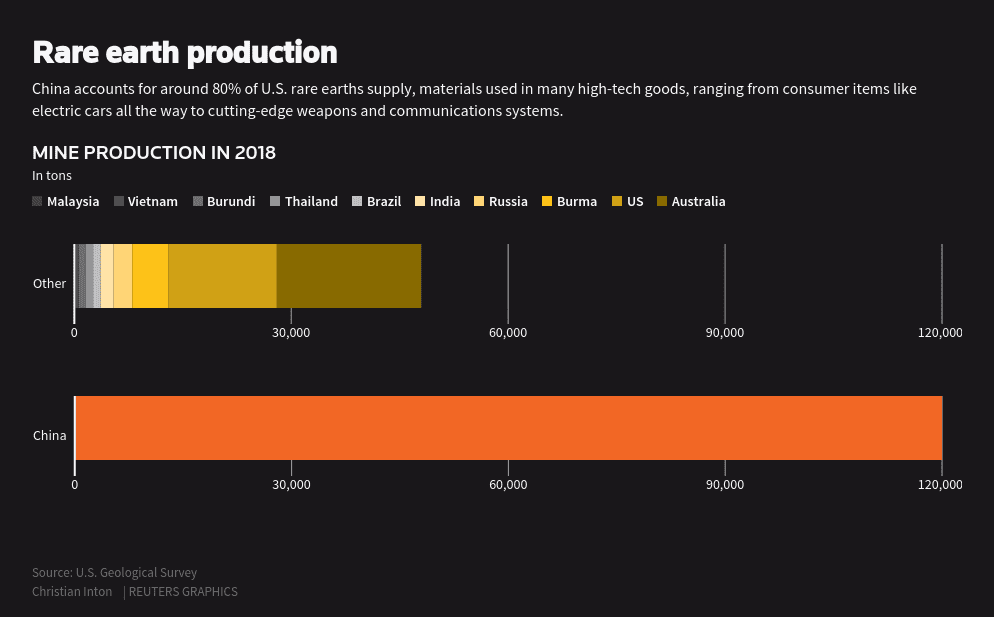

Given that China currently produces somewhere between 80 and 85% of the world’s rare earths, there are reasonable grounds for speculation that China could utilise its position of dominance to gain leverage in trade talks. China itself has made thinly-veiled overtures in this regard, as Chinese President Xi Jinping recently paid a visit to a rare-earth metals production facility.

But of course China has tried this before, back in 2010, without success.

The key however is that rare earths aren’t ‘rare’ and in the case of the USA, for the past 25 years it has been happy to allow China to supply it at prices it was more than happy to pay. China’s monopoly has been won by its ability to supply the market at low prices and the fact that rare earths production is a messy business, often with environmental consequences. The rest of the world, in particular the USA, has been happy to outsource production to China – for both cost and environmental reasons.

So the bottom-line is that if China wants to raise its prices and start using supplies as geopolitical bargaining chips, the rest of the world could simply ramp up production, with China’s monopoly broken.

If we look back to Chinese supply threats in 2010, there were positive impacts on the most advanced western world production plays. One very high-profile example was Molycorp, the operator of the Mountain Pass mine in California. The company sold shares at $14 apiece in its New York initial public offering in July that year. Rare earth prices rose and by May 2011 its share price hit $75, giving the company a market capitalisation of more than $5 billion.

The problem was that despite much speculation, a true physical shortage of rare earths never materialised. Prices peaked in 2011 and eventually gave up most of their gains. More supply came onto the market from Australia and Malaysia – which is a perfect example of demand-supply economics in action.

Molycorp attempted a strategic pivot by acquiring Neo Material Technologies, a Canadian metals processor, for $1.2 billion in 2012. But relentless rare earth price falls proved ultimately to be the death knell for Molycorp. Quite simply it couldn’t generate sustainable earnings and by early 2015 it was talking to debt-restructuring advisers. The company filed for bankruptcy protection in June 2015.

It was a similar situation with Lynas Corp (ASX: LYC), which secured financing for its Malaysian processing plant. Like Molycorp, the problem was that earnings collapsed as soon as we got the inevitable market response to the China supply threat, incentivised by higher prices. Lynas was forced to engage in an enormously dilutive capital raising.

Even credible emerging producers like Northern Minerals (ASX: NTU) have fallen into decline. The graphic below reflects the share price performances of both NTU and LYC since 2010.

The takeaway for investors is that developments like the trade war don’t necessarily result in a longer-term profitable environment for companies in the rare earths business.

This doesn’t detract from the fact that another Chinese export ban won’t generate near-term sharemarket opportunities. We’ve already seen this reflected in some junior ASX-listed rare earths plays, which have been promoting themselves based on their leverage to rising rare earths prices. The problem is that most of these plays won’t come anywhere close to making it into production.

Summary

The bottom-line with respect to rare earths is to be very careful. Most, if not all, are plays on market sentiment, not the beginnings of proper world-class mining enterprises. The market at present is simply too small to support another large scale producer if China returns to the export market.

Prices for a handful of the elements – neodymium, praseodymium and dysprosium – have recently jumped, though they are nowhere near the dizzying highs seen eight years earlier. The real point here is that rare earths just aren’t rare enough for anyone to ever gain an exploitable lock on their production. Thus profits are difficult in the rare earths industry.

Disclaimer: Gavin Wendt, who is a director of Mine Life Pty Ltd ACN 140 028 799, compiled this document. It does not constitute investment advice. I wrote this article myself, it expresses my own opinions and I am not receiving compensation for it. In preparing this article, no account was taken of the investment objectives, financial situation and particular needs of any particular person. Investors need to consider, with or without the assistance of a securities adviser, whether the information is appropriate in light of the particular investment needs, objectives and financial circumstances of the investor. Although the information contained in this publication has been obtained from sources considered and believed to be both reliable and accurate, no responsibility is accepted for any opinion expressed or for any error or omission in that information. I have no positions in the stock mentioned and no plans to initiate any positions within the next 72 hours.