State Reserve Funds are quietly draining metal and liquidity in physical copper out of the copper market in anticipation of substantial new demand.

Slowing global growth combined with news on the US-China trade war has held industrial customers back from buying, while hedge-fund selling and a stronger dollar has helped to lower copper prices.

However, the long-term state planners of China’s Communist Party and maybe even some Western powers are aware that copper is going to be critical for infrastructure development if the world is to move towards using electric vehicles (EVs).

Copper prices fell to their lowest in two years in August 2019 as President Trump vowed to impose even more tariffs on Chinese imports, causing macro traders to sell short and other funds to dump their long positions. Resolving the trade war could be the catalyst for the copper price to move significantly higher. There has been recent optimism about this following news that the White House is considering removing tariffs on USD 112 billion of Chinese imports.

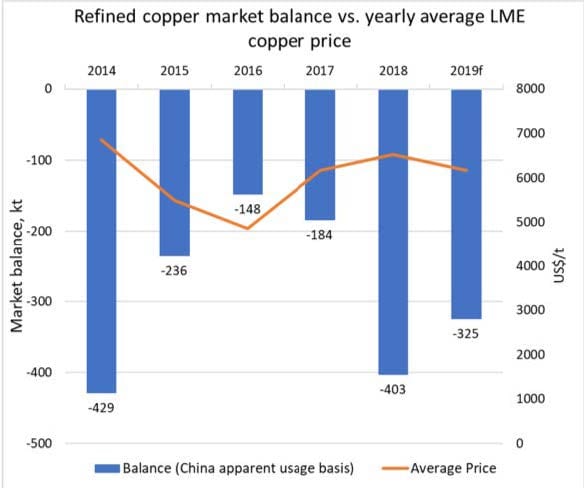

For copper to continue moving higher, a Phase 1 trade deal would need to be signed and talks between the countries continue to strengthen. The price could advance further if protests in Chile, strike action at Grupo Mexico mines in the US, and other disruptive events cut mine output. While LME warehouses have seen substantial outflows, copper prices have seen little movement this year, rising just 1.6 percent to USD 5,910 (Jan-Nov).

Future Demand of Copper

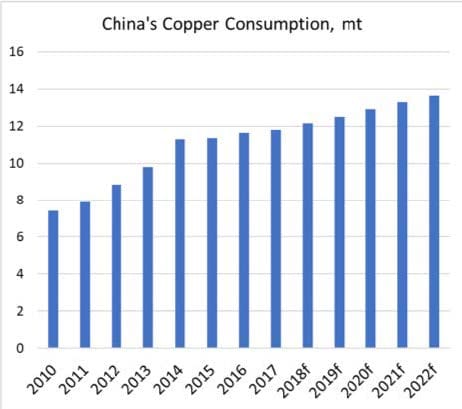

According to the International Copper Study Group (ICSG), refined copper usage grew by 0.5 percent in the first seven months of 2019 despite global usage (excluding China) falling by 1.5 percent, indicating how important Chinese growth is to global demand. Global refined usage has been lower than anticipated due to the slowdown in China, which fell to 6 percent in the third quarter, the lowest quarterly growth rate since official records began in March 1992.

Chinese net refined copper imports declined by 15 percent as traders reigned in their purchases despite Chinese copper usage still growing by some 2.4 percent. China accounts for around 50 percent of global copper demand, and future development of its power and construction sectors will require vast amounts of the metal.

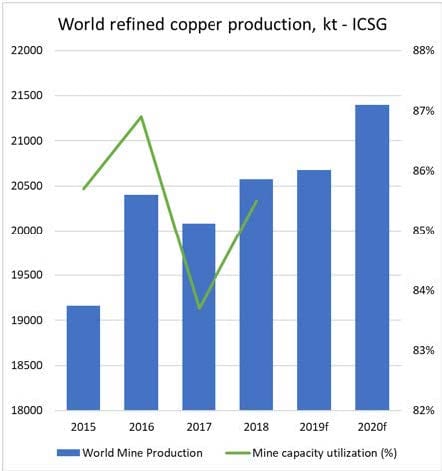

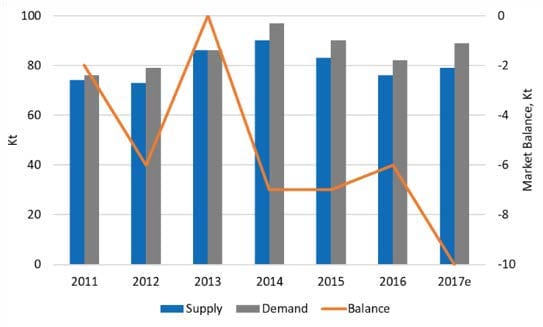

Supply and Deficit

According to the ICSG, global mine production fell by some 1.3 percent in the first seven months of the year as output fell in all the major copper producing regions, caused by problems in Chile, Indonesia, the DRC, and Zambia. Production would have fallen further if Peru, the world’s second largest producer, had not picked up.

The ICSG estimate that in the first seven months of 2019, the copper market recorded a supply demand deficit of 325,000t, a figure which is likely to grow as ongoing protests and disruptions impact more production.

New Demand Growth

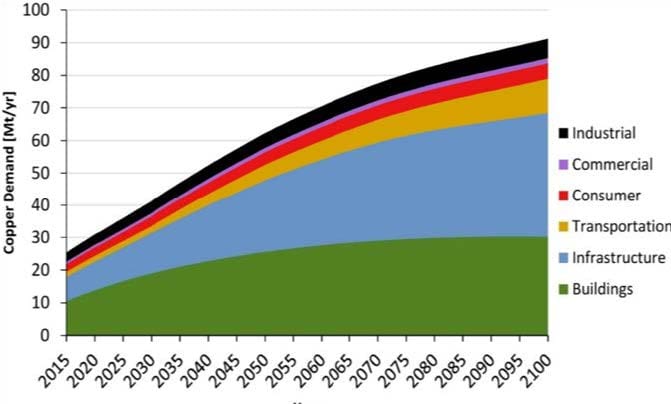

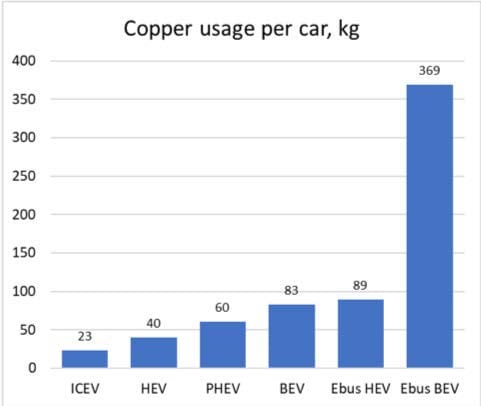

That said, the growing EV market and the shift to renewable energy systems will generate fresh demand for copper. The German Chancellor, Angela Merkel, publicly stated that she wants one million new charging points in Germany to help drive the EV revolution.

Growing size of battery packs in EV at nearly 60kWh indicate substantial new demand for power from local utilities.

While one million EVs and their chargers are estimated to use 153,000t of copper, the installation of just 10GW of wind turbine capacity would use around 44,500t of copper. Last year, EVs on the road consumed 58TWh of electricity (mainly electric bikes in China), indicating the scale of the challenge for power utilities. The International Energy Agency forecast new electricity demand for EVs globally to reach almost 640TWh in 2030. If wind turbines operated at 100 percent capacity then this would require 73GW of capacity. However, the reality is that most wind turbines are more likely to run at roughly 25 percent capacity than 100 percent. Therefore, the total required wind turbine capacity would need to be more like 292GW to meet this need – and that’s assuming 100 percent energy-efficient storage was available.

Given that battery storage is around 75 percent efficient (accounting for some transmission losses), we could get away with 365GW. Add 20 percent for redundancy and spare capacity and we are at 438GW, which indicates that the world might need to produce 2Mt of copper if it were to supply all of these EVs using wind power. As the world produces just 24Mt of copper a year, this is an appreciable amount of new demand required by the market.

Germany has around 200GW of installed capacity, indicating that substantial new power generation should be installed if the new army of EV owners are to drive their new cars on a regular basis. The UK has 21.5GWh of wind power by comparison. New global wind installations added a further 51.3GW of wind power consuming around 230,000t of copper, bringing global installed capacity to 600 GW (~2.7Mt copper). However, the European Wind Energy Association expects another 195GW of new wind capacity to be installed in the EU alone by 2020 and 320GW by 2030. This would require around another 900kt and 1.4Mt of copper respectively.

The Global Wind Energy Council believes that wind power generation capacity could grow to 2,110GW by 2030, supplying 20 percent of global electrical power. Current installed wind power capacity is ~597GW, with an expected further 1,513GW of capacity to be built consuming around 6.7Mt of copper not including power cabling from the wind farms to the grid or any electrical cabling for the new battery instillations to support variability of wind and other renewable power sources.

In conclusion, we believe that long-term players are likely to be rebuilding stocks of copper to feed new infrastructure for renewable energy generation and electric vehicle support.

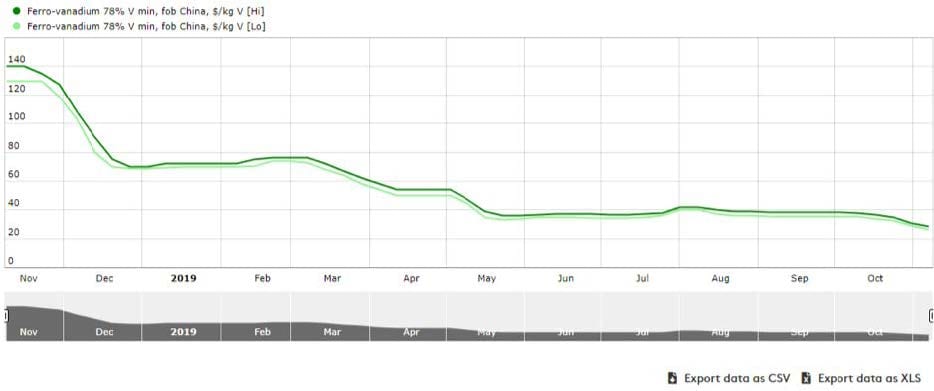

Vanadium: Down but Definitely Not Out

Expect vanadium prices to recover sharply in the next few months as buying returns to the market. Vanadium prices hit a peak of USD 140/kg in October 2018 with buying related to new Chinese regulations regarding specific grades of hardened steel. Prices for ferro-vanadium 80 percent FOB (China) hit USD 20.0/kg and USD 20.5/kg recently in Western Europe according to Fastmarkets MB. Many Chinese steel producers had been using quenching and tempering processes to harden steel, however this can lead to sudden catastrophic failure when the steel is overly stressed as may happen due earthquakes and subsidence.

Vanadium in Steel

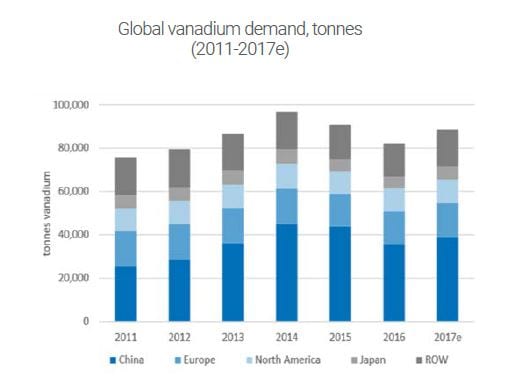

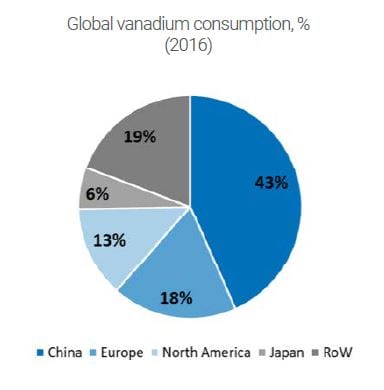

The new Chinese regulations require substantially more vanadium in the steel, driving demand higher. Unfortunately, higher vanadium prices, poor compliance in China, and substitution with niobium have caused demand to fall, with vanadium prices pulling back to USD 27.5/kgV in China and USD 20.25/kgV in Western Europe.

The leaching of some vanadium-rich tailings is seen as providing some temporary new supply to the market, though observers reckon this source should be worked through by the year-end.

Liquidity and Infrastructure

A lack of financial liquidity through 2019 combined with worsening sentiment relating to the US-China trade war has hit new construction and demand for strengthened steel products, causing buyers to hold back on vanadium purchases.

Infrastructure projects are the fastest way to restore economic growth. We expect new liquidity to come into the construction sector as policymakers work to restore confidence and reflate Western economic growth.

Chinese policymakers may also accelerate new belt and road projects and some other local infrastructure as they work to offset the negative impact of tariffs on the US. The good news is that China appears determined to enforce strict environmental and metallurgical compliance.

Environment regulations impact on Vanadium Production

Environmental controls have cut out secondary vanadium production from stone and the reprocessing of vanadium-bearing steel slag. Strict enforcement of vanadium content in key grades of steel should also drive new demand. China has restricted the use of lower-grade steel which will also drive demand for higher-grade vanadium-bearing steels.

New demand is also expected to come from Vanadium Redox Flow Batteries (VRFBs) which are aimed at supporting wind and solar power farms. The new green agenda at the World Bank is set to replace ageing coal-fired power generation with new renewable wind and solar plants which will need battery backup to ensure consistency of electrical supply. VRFBs are well placed to operate alongside and in place of lithium-ion batteries, which have generally lower energy capacity and shorter discharge timeframes but can discharge faster.

We suspect power networks will eventually incorporate a range of new power storage technologies with smaller lithium-ion batteries operating alongside much larger VRFB systems which are well suited to longer-term (8-hour) discharge.

We forecast that VRFB demand in southern Africa alone could consume over 5 percent of global vanadium production over the next few years, creating significant new demand in a market where supply is relatively inelastic. If this trend is repeated in the US, China, and Europe, then we can predict new demand for vanadium easily outstripping supply in future years with grid developers queuing to secure available vanadium electrolyte supply.

The new availability of lease/rental financing for the vanadium in VRFB batteries should serve to offset the high cost of vanadium in the batteries, enabling the planning of more installations as vanadium comes available.

In conclusion, vanadium prices are down but definitely not out. The market is still digesting some new temporary supply at a time of slow buying activity, causing prices to fall further than would normally be expected.