Recent moves into trading

Trading can mean different things for different mining companies. It can simply mean a miner selling its production directly, rather than through traders, controlling the logistics and gathering valuable market information in the process. It can also mean trading third party material and taking speculative positions in physical or derivatives markets.

In recent years, most of the moves across the commodity value chain have involved traders shifting upstream, acquiring mines and processing operations. Examples include trader Glencore’s merger with miner Xstrata in 2013. Glencore trades over 4Mt of copper metal and concentrates, versus production of around 1.3Mt. Trader Trafigura has also acquired several mines and processing facilities, including Nyrstar last year.

It appears the big miners are increasingly looking at ways to further monetise their trading books. With balance sheets restored in recent years, thanks to recovering commodity prices, major cost reduction programs and a more disciplined approach to growth, both organic and acquisitive, miners are looking at further opportunities to improve margins. An example in recent years being a focus on shipping, an area which didn’t historically attract much attention.

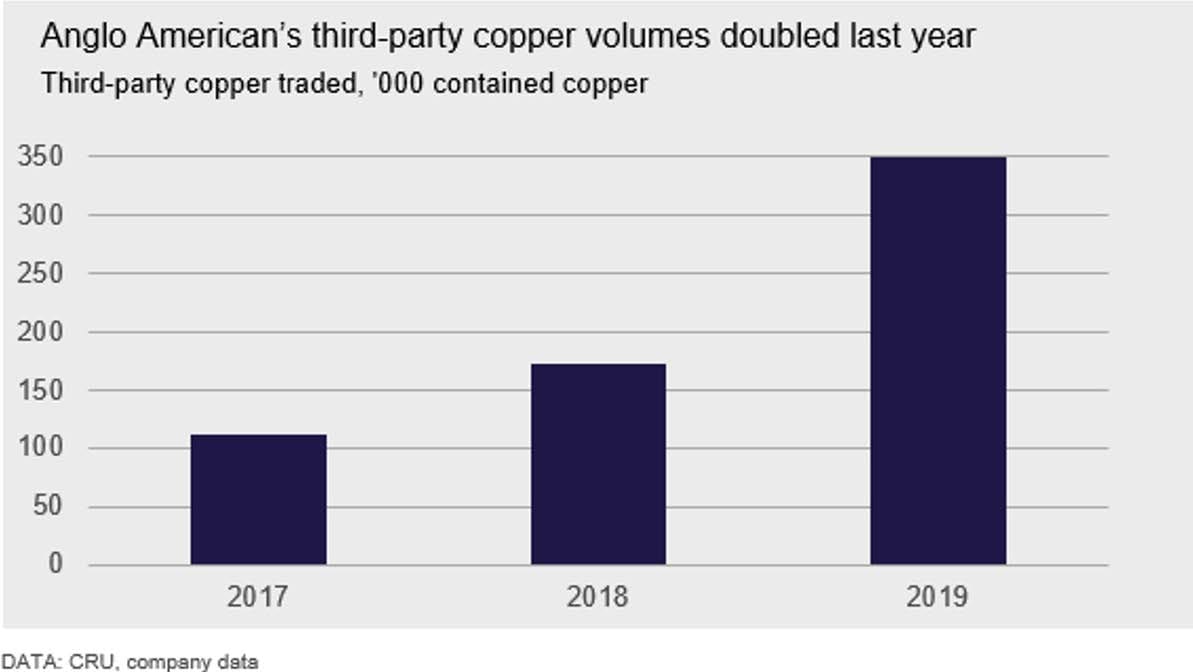

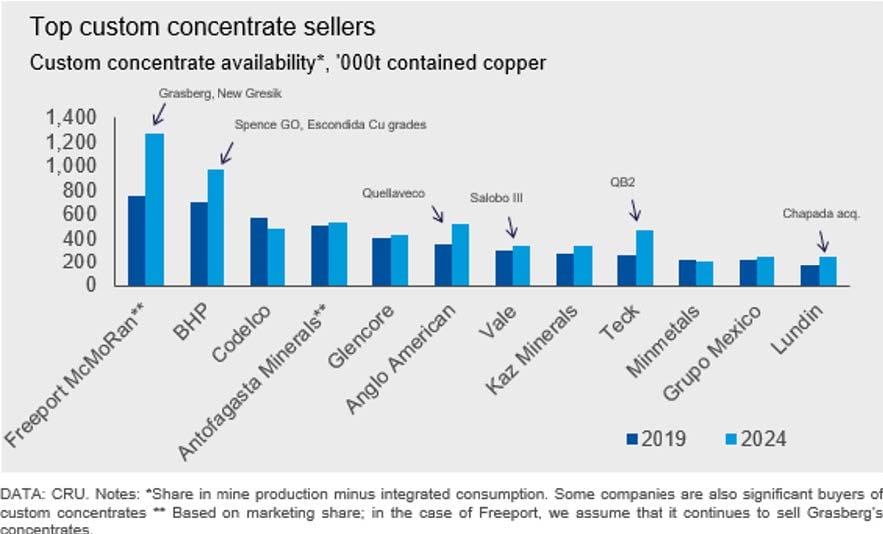

Anglo American appears to be successfully building its trading business across several commodities, including copper metal and concentrates. Anglo’s marketing offices globally were merged into a single trading division based in Singapore in 2013. The trading strategy was initially implemented in their platinum business, and was then replicated in coal, iron ore and copper. Trading seems to have initially focused on logistics and gathering marketing information from trading their own products. Anglo soon progressed to buying and selling third-party production, including copper concentrates. In 2017, Anglo traded 111,000 tonnes of copper from third-parties, on top of its own production of 579,000t. Third-party copper volumes increased 56% to 173,700t in 2018 and then doubled last year to 349,000t. To date this activity has been focused on physical markets, but we understand Anglo is now moving to financial markets (derivatives) in refined copper. Anglo’s marketing initiatives added $400m to earnings in 2015, a year earlier than targeted. Although it should be noted this was across a range of commodities and a range of initiatives across marketing, including price realisation, sales channel and freight optimisation. Anglo reports the financial contribution from trading in three of its business units but is yet to disclose its contribution from copper trading.

China Molybdenum Co. (CMOC) acquired Louis Dreyfus Company’s metals trading business, IXM, for $518m in 2018. Both parties were actively pursuing a deal, and we understand many parties submitted bids for IXM. CMOC wasn’t solely driven by the opportunities IXM presented in copper concentrates, a market in which IXM has a substantial presence, currently handling in excess of an estimated 2Mt per year of copper in concentrates. A longer-term view was taken, across a variety of metals including copper, zinc and lead concentrates and refined metals including cobalt, molybdenum and nickel. Acquiring IXM provided a platform for CMOC to undertake its own marketing and leverage its expertise.

BHP (LON: BHP)has been trading its own commodities for many years. However, the company’s trading business had focused mostly on procurement and it is only recently that BHP has purportedly begun to trade third-party copper concentrates to optimise its books. BHP started its BMAG marketing operation around fifteen years ago but subsequently closed it down. Through this business BHP was selling its marketing expertise as a service. BHP has more recently (2018) been reported as saying that ultimately any trading business would need to drive margins and returns. However, at the time, BHP also noted that from a capital allocation perspective this couldn’t compete with the expected returns offered by other projects in the company’s portfolio. At this stage BHP is not moving towards an asset backed trading model.

Rio Tinto (ASX: RIO) is also believed to have recently entered swap deals, exchanging material from its Oyu Tolgoi mine for other concentrates. This provides Rio Tinto with a comparative valuation of its product to CIF terms, enabling the company to capture spot terms. That said, there is difficulty comparing CIF terms across different qualities, and tenders for OT material already provide a competitive valuation. Vale (BVMF:VALE3) have also been mentioned as having an interest in developing their trading strategy and,

although not officially stated, Vale’s agreement with OZ Minerals (ASX: OZL) to buy and sell Pedra Branca’s concentrates might be interpreted as a move in that direction.

Potential benefits for miners moving into trading

A range of factors could be behind miners looking to develop trading businesses, including the following:

The opportunity to cut costs by internalising the trading margin. The benefits of this extends further upstream to logistics and mining operations.

The size of the traded market relative to global copper concentrates production, particularly with the growth in demand in China where many smelters are reliant on third party concentrates – this has increased the size of the opportunity for miners.

A competitive response to China’s Smelters Purchase Team collective of large smelters. Directly controlling more tonnes may give the big miners more negotiating power.

Access to third party tonnes helps to manage non performance risk, ensuring orders are met in the event of disruptions at mining or logistical levels.

Information access and developing relationships with a broader base of customers – helps miners gain valuable market insights. The value opportunity in blending, increasing copper, gold and silver payables. The average traded copper concentrate grade has fallen sharply in recent years. Also, to reduce deleterious elements in concentrates, particularly arsenic, to below China import limits.

Moving into trading may help miners expedite the shift from annual benchmark TC/RCs to shorter-term pricing, including quarterly, spot and index mechanisms.

The acquisition of a trader provides miners with an alternative way of investing in other mines, than investing directly through equity stakes in mining companies. A trader can lend to a mining company through a loan or prepayment, secure offtake, earn a return and be able to exit the arrangement relatively quickly.

As miners’ balance sheets have repaired in recent years and as potential returns from mining projects arguably become more challenging with declining resource quality, increased costs, regulations and community challenges, opportunities to improve margins through trading become more attractive on a relative basis.

Shipping fuel regulations, such as IMO 2020, increased shipping costs. This makes it increasingly important for miners to use swaps to cut costs, increase flexibility and ensure timely delivery.

Responsible sourcing is becoming increasingly important and arguably easier for better resourced, larger companies to do this than for small traders. This also applies to use of blockchain payment technologies.

Several banks have divested their commodity trading units in recent years because of increased regulatory pressure. The changing market structure may be creating more opportunities for miners to enter.

Key challenges

We expect the big miners to move further into the trading of copper concentrates, to capture the value associated with this. However, we see two main challenges for the big miners:

Firstly, the big miners appear to have much stricter structures in place, compared with trading firms, in the areas of risk management, contracting and hedging. This requires adherence to strict guidelines, which may impact their ability to capture opportunities.

More specifically, in contracts, each miner has their own terms and conditions, which differ from company to company. These differences are likely to make it difficult for the large miners to do deals with other large miners, particularly if neither party is willing to negotiate on terms. Similarly, smaller and mid-sized miners have a wide range of traders and smelters to sell to and therefore may be less willing to comply with the contractual terms and conditions of the big miners.

Secondly, risk appetite is likely to be smaller compared with that of commodity trading firms. It remains to be seen whether the big miners would be willing to take a speculative position based on their view of the forward curve.

One option is for miners to enterback-to-back trades with other miners, traders or smelters. However, given there is always a gap between minertrader and trader-smelter terms, they are likely to incur losses doing this.

While blending offers an opportunity, we view it as unlikely that the large miners will want to get significantly involved in this given the costs and the expertise required to manage all of the impurities.

It is more likely that the big minerswill optimise their book by engaging in swaps with mines and traders where it makes sense. This will provide the opportunity to create additional margin, as well as providing access to valuable market information. It will also help manage non-performance risks.

Shareholders have sent a clear message to the boards of major mining companies over the past decade that they want to see investment in value accretive growth, and return surplus capital to shareholders in the form of higher dividends and share buybacks. If a trading business increases a miner’s earnings volatility, this would likely attract a valuation multiple de-rating, potentially having an adverse impact on the company’s stock price. Trading businesses also tie up significant amounts of working capital and have to compete for returns with other projects in miners’ portfolios. While mining is inherently risky, shareholder appetite for potential losses appears to have decreased over the years. An example is the reduced use of commodity and currency hedging, outside of that mandated by banks as a condition of financing agreements, following substantial losses incurred by miners in the early 2000s. More recently, shareholders’ appetite for mergers and acquisitions was impacted by many value destructive deals undertaken around a decade ago. Shareholders of the big miners are unlikely to have the appetite for the occasional substantial losses that come with speculative trading. As such, we would expect the big miners to retreat from any trading initiatives if they do start to incur significant losses.

The other challenge is the service offering and relationships required. Traders hold stock, can store material, blend concentrates, have deep relationships with smelters and can provide finance. The main traders have extensive relationships with a broad range of smelters globally. By comparison, the relationships held by large miners tend to be focused on the larger smelters in a limited number of key markets.

Finally, from a timing perspective, one may ask why a miner would bother risking capital trying to capture a relatively small trading margin at a time when the copper price is ok, treatment charges are at near multi-year lows, and with the market seeing new entrants in recent years, bidding competitively for volumes.