Within the mining community, there is much discussion about the bright future for nickel demand – driven by electric vehicle adoption and the grid-scale storage necessary for renewable power generation. Thanks to Elon Musk, nickel’s newest and now highest profile cheerleader, this topic is transcending mining circles and becoming common knowledge among investors. I share this enthusiasm for nickel’s long-term prospects and expect global nickel demand to increase roughly two-fold from 2.2 to 4 million metric tonnes by 2030 as EV and renewable trends accelerate.

Supply Challenges

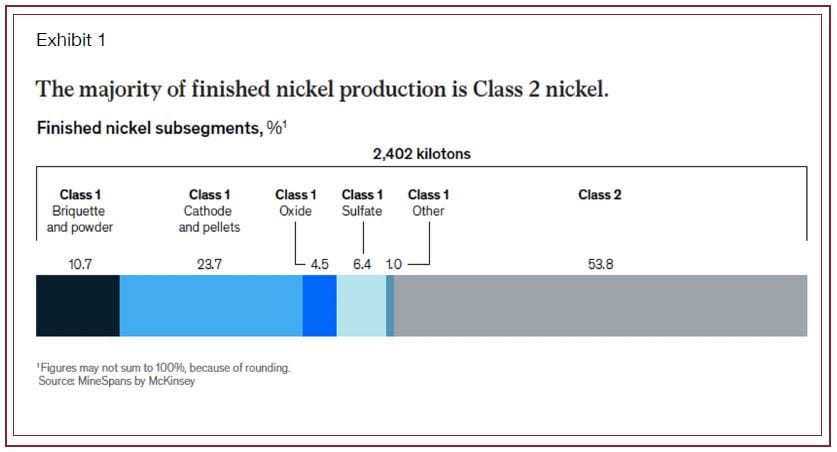

There is a marked underappreciation for the challenges in supplying enough metal to satiate the anticipated battery-driven nickel demand – even assuming significant increases in the nickel price over the coming years. The facts are relatively straightforward. As estimated by MineSpans, only 46% of global nickel production is of sufficient quality and purity to be used in battery cathodes. We refer to this as Class 1 nickel (See Exhibit 1).

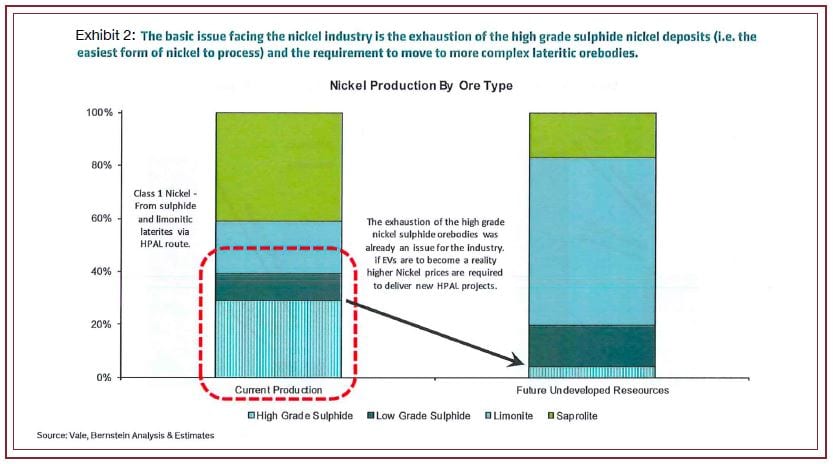

Roughly 70% of current Class 1 nickel production is derived from sulfide ores – with the remainder originating from limonitic laterite deposits. Sulfide deposits are relatively easy to exploit through conventional underground or open pit mining, smelting, and refining. Laterites, on the other hand, require intensive hydrometallurgical processing methods and are referred to as “glorified chemistry experiments” by industry cynics.

While current Class 1 nickel production is dominated by sulfides, the basic issue facing the industry is that large, high quality sulfide deposits are becoming increasingly difficult to find as the low hanging fruit has already been plucked in previous mining cycles. As such, roughly 73% of undeveloped nickel resources globally are now hosted within laterite deposits. New sulfide deposits will continue to be discovered in the years ahead, but not nearly at the pace necessary to keep up with battery-driven demand. For better or for worse, the future of Class 1 nickel supply is very much dependent on these known yet undeveloped limonitic laterite deposits being successfully commercialized.

Nickel Laterite Overview

Before delving into the challenges this presents, we’ll start with the laterite basics. These deposits are formed near or at the surface following the extensive weathering of ultramafic rocks. Laterites are found primarily in tropical climates near the equator in Indonesia, the Philippines, Brazil, New Calendonia, and Cuba. (There are also “dry laterite” deposits found in arid climates such as Western Australia and Southern Africa.) There are two main classifications of laterite ore: limonite or saprolite. As mentioned previously, some (but not all) limonitic laterites are suitable for Class 1 nickel production. This is not the case for saprolitic laterites; nickel produced from this style of deposit feeds into the stainless steel industry as Class 2 nickel.

Laterite deposits are typically large, low-grade, and extracted through shallow mining. The typical flowsheet is complex and varies from mine to mine. However, one common processing step in laterite operations producing Class 1 nickel is high pressure acid leaching (HPAL). HPAL entails laterite ore being fed into an autoclave along with sulfuric acid at temperatures up to 270°C and pressures up to 725 psi to separate the nickel and other byproducts (e.g. cobalt) from the ore. At this stage, some operations have an integrated refinery to produce nickel briquettes, powder and pellets, while others produce an intermediate nickel hydroxide or nickel sulfide product for export to a downstream partner. (It should be noted that a few of the laterite projects under development, such as Clean Teq’s Sunrise Project and Ardea’s GNCP, propose a nickel sulphate end product.)

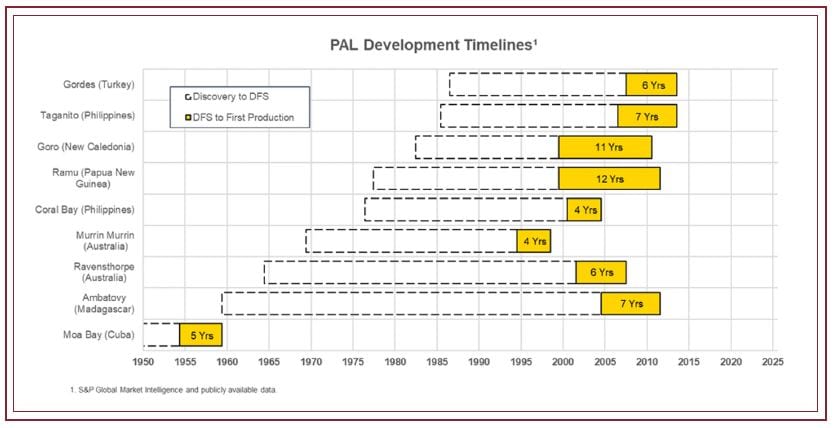

Today there are a handful of major laterite mining operations successfully producing Class 1 nickel via HPAL processing. Examples include Coral Bay and Taganito in the Philippines, Moa in Cuba, and Ramu in Papua New Guinea. But in recent decades we’ve seen nearly as many high-profile HPAL failures, where billions were sunk into projects that are now either on care and maintenance (Goro), operating at production levels well below anticipated nameplate capacity (Murrin Murrin), or have failed outright (Cawse and Bulong). The construction and commissioning of any mine is a high risk and oftentimes painful endeavor, but it must be said that HPAL operations have a particularly poor track record.

Laterite Production Challenges – Performance, Capex, & ESG

There are three main factors that future developers of limonitic laterites via HPAL will have to contend with. The first is that the chemistry required to successfully process laterite ore into a saleable product at scale is incredibly complex.

Notoriously, results obtained from lab-scale and even demonstration-scale HPAL testing do not often hold up in a commercial setting. Just look at Murrin Murrin, which first went into production in 1999. While operating for the past two decades, nickel production has not once met the originally expected nameplate capacity of 45,000 tonnes of nickel per annum. (Peak production of 40,000 tonnes was achieved at Murrin Murrin in 2013, while the annual average for the past decade has been roughly 35,000 tonnes.) The oft-maligned Ravensthorpe is another example. Production has never achieved the initial expectation of 50,000 tpa and current owners First Quantum seem content with 25,000-28,000 tpa going forward.

Interestingly, the HPAL projects that have been most problematic are those that targeted annual production levels north of 40,000 tpa. Projects in the 20,000-30,000 tpa range (such as Moa, Coral Bay, Taganito, and Ramu) have executed relatively well in comparison. While it is tempting to build these projects as large as possible to maximize economies of scale, history tells us this may be a mistake that risks operational underperformance.

Another clear challenge is that laterite HPAL operations are expensive to build with a penchant for construction delays and capex overruns. A good industry rule of thumb is that anyone who tells you they can build an HPAL operation for less than US$1 billion is either delusional, misinformed, or a liar. In low metal price environments, projects of this scale simply don’t get built. This however can change in the mid to late stages of metal bull markets, which is why we saw a series of HPAL projects get the green light between 2004-2007.

This late cycle enthusiasm leads to an associated problem surrounding this type of mining operation – a history of major capex blowouts. BHP for instance projected an initial capex of US$1.05 billion at Ravensthorpe when construction commenced in 2004. When the project finally reached first production in 2008, that number had more than doubled to US$2.2 billion.

It was a similar story at Murrin Murrin in the late 1990’s – where we saw the original cost estimate of US$1 billion blow out to US$1.6 billion before initial production was achieved. But these overruns look tame when compared to Ambatovy in Madagascar where the actual capex was roughly triple original estimates or Goro in New Caledonia where the final cost was more than quadruple expectations. These horror stories won’t soon be forgotten by snake-bitten investors and industry participants.

Why the pattern of delays and capex overruns? The complexity of these operations surely plays a part, resulting in design flaws and engineering issues. Additionally, the selection of shoddy construction materials and equipment unable to withstand the corrosive, high-temperature, and high-pressure environment has proven to be a repeated mistake. And perhaps most importantly, the timing of construction decisions towards the top of mining cycles leaves these projects particularly prone to cost inflation and procurement delays.

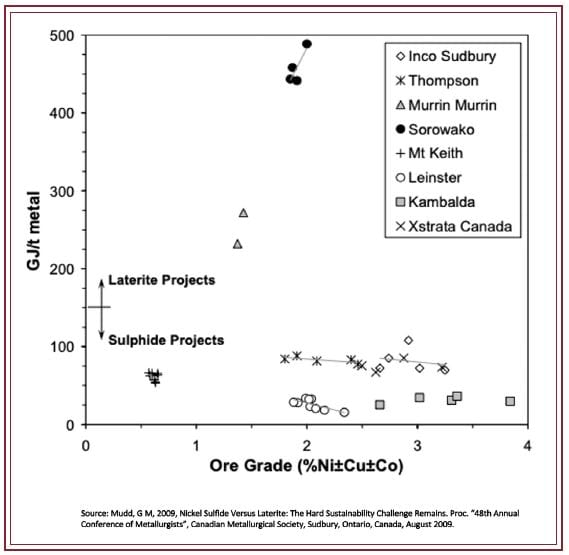

And finally, there are the ESG concerns. In a general sense, nickel laterite operations are more energy and CO2 intensive when compared to sulfide projects. In a 2009 study, Dr. Gavin Mudd determined that major laterite operations require 2.5 to 6 times more energy per tonne of nickel produced when compared to sulfides. This study however included ferronickel and NPI laterite operations, which are particularly energy intensive. HPAL operations, especially those with an acid plant on site, would be on the lower end of Dr. Mudd’s range.

From a greenhouse gas perspective, a recently completed study by Energetics found that HPAL operations produce 24-27 kg CO2e / kg Ni. This compares unfavorably to sulfide operations, which range from 8.8-18.8 kg CO2e / kg Ni. For HPAL, roughly one-third of the carbon emissions can be attributed to imported electricity, one-third to acid neutralization using limestone, and one-third to logistics and other reagents.

There are also the more immediate environmental and social concerns posed by the large mining footprints and the use of sulfuric acid. Goro for instance faced years of opposition, sabotage, and legal wrangling by members of the indigenous Kanak population before finally reaching an accord in 2008. Then, a sulfuric acid spill at the operation in 2010 followed by effluent spills in 2012 and 2014 proceeded to attract the ire of environmental NGOs. Similarly, the large volume of tailings inherent with laterite operations has proven to an acute point of contention. The Ramu HPAL operation in Papua New Guinea.

has faced opposition for years now over its practice of deep-sea tailings disposal and is currently the subject of a $5 billion class action lawsuit. As the spotlight on ESG intensifies, there is no evidence to suggest that navigating through these environmental and social challenges will be any easier for the next generation of laterite mining operations.

In Summary

This wasn’t intended to be a full-throated indictment of nickel laterites, but rather a realistic look at just how difficult this type of mining operation is to pull off. Despite the aforementioned hurdles, I do in fact expect that a handful of currently undeveloped limonitic laterite deposits capable of Class 1 nickel production will receive positive construction decisions this decade. This is simply the only way that the mining industry will be able to meet anticipated Class 1 demand in the coming years given the trajectory of battery cathode chemistries and the dearth of new nickel sulfide discoveries. However, history tells us that these upstart HPAL operations will face similar issues to their predecessors — operational underperformance, capex overruns, construction delays, and environmental / social opposition. When this occurs, nickel end users, investors, and mining industry participants have no excuse to be caught by surprise.