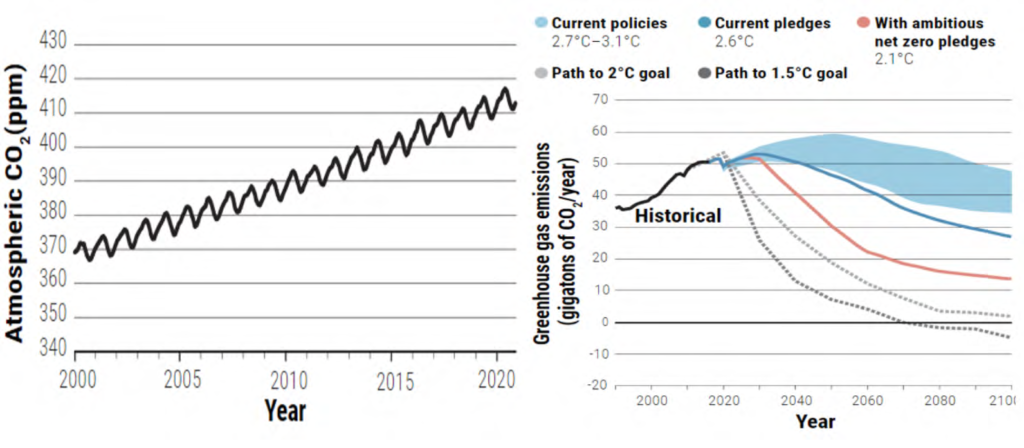

Achieving the goal of the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement (to limit the global temperature rise to less than 2ºC) is ambitious, despite many countries, including the European Union, Canada, South Korea, Japan, and the United Kingdom pledging to be carbon neutral by 2050. Without any changes in behavior, temperatures are forecast to jump by 3.5ºC, but the implementation of current pledges may still cede a 2.9ºC rise.

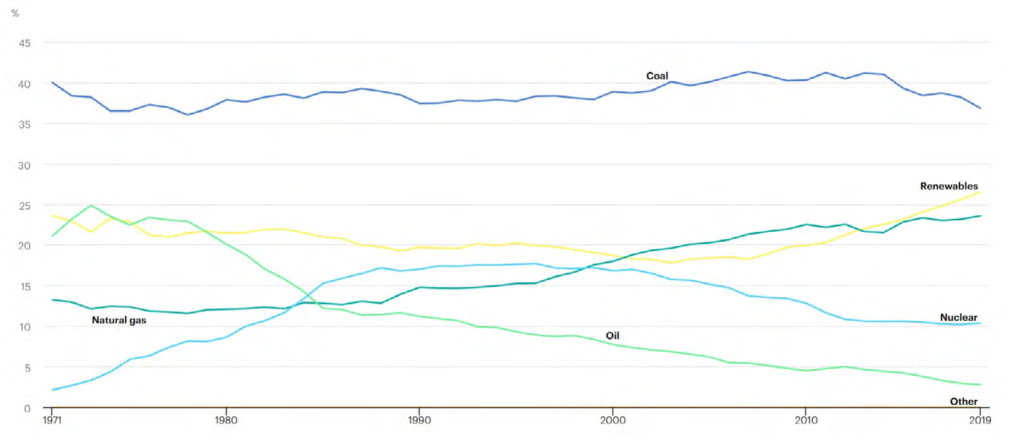

Integral to the plan of reducing carbon emissions, is a green revolution that requires a dramatic shift of energy sources from oil, natural gas, and coal to renewable technologies (hydro, nuclear, solar, and wind) and a reduction in the number of internal combustion engines (ICEs) on the road.

Canada has defined a critical mineral as one that is required for the transition to a future low-carbon economy and suffers from supply chain insecurity while having the potential to be a sustainable source of supply to trading partners and allies.

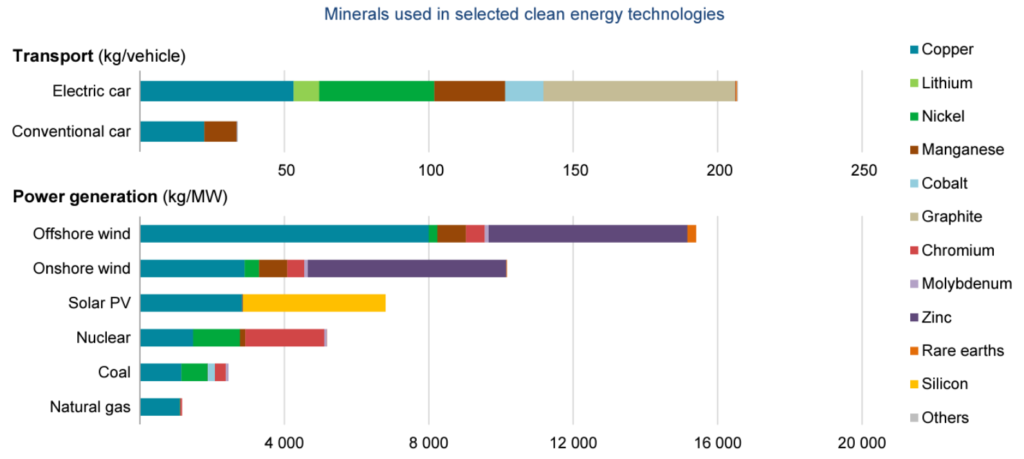

Metals instrumental to the current electric vehicle (EV) battery chemistry, including lithium and rare earth elements (REEs), may be a strong focus of government bureaucrats, but they form only a portion of a holistic carbon-neutral plan. Clean power technologies and modifications to infrastructure are also important and require other metals including copper and aluminum.

Unfortunately for policymakers and their advocates, there exists a sizeable chasm between the Western world’s aspirational climate goals and the path to achieving them. The mining industry, which may be the lynchpin in the carbon neutral plan, is facing an uphill battle to find, permit, fund, extract, and process the critical minerals required for the green revolution in a fragmented global economy.

The issues include (but are not limited to) the following:

- Incentive prices – Commodity prices are subject to the vagaries of near-term volatility which may not incentivize exploration, development, or expansion of projects to support the appetite for critical minerals. Price increases that favor only a few critical minerals are insufficient when the entire complex needs to move in unison. Recent M&A activity in the lithium and copper sector is a positive sign that the industry is aware of the upcoming gap in supply, but consolidation does not necessarily add to the future production profile.

- Source of critical minerals – The Russian invasion of Ukraine in the first half of 2022 triggered an energy crisis in western Europe, specifically Germany, due to its exposure to natural gas imports from Russia. The case study provided a stark example of the risk of placing all your eggs in one basket. Other major Western economies such as the US, on the other hand, are better placed for energy security with limited dependence on Russia for oil or natural gas. However, with respect to critical minerals, the supply chain risk of obtaining some critical minerals; namely cobalt (DR Congo), graphite (China), platinum (South Africa), palladium (Russia), and REEs (China), is recognized as being problematic. As a result, the Minerals Security Partnership (MSP) was established between Australia, Canada, Finland, France, Germany, Japan, Korea, Sweden, the United Kingdom, the United States, and the European Union with an underlying goal of “…ensuring that critical minerals are produced, processed, and recycled to realize the full economic development benefit of their geological endowments.” Worryingly, regions with significant mineral endowments in South America (Brazil, Peru, Chile, and Argentina) and Africa (DR, Zambia, etc.) are not involved.The segmentation of supply is further exacerbated by the higher proportion of critical minerals and battery parts required by 2029 to be sourced from the US or free trade agreement (FTA) countries to earn the EV credit of US$7,500 outlined in the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). Even countries such as Chile, Peru, and Mexico, with whom the US has FTAs, (but are led by socialistic governments) have only become riskier for foreign direct investment (FDI) in the mining sector over the past several years. For example, Newmont Corp. (NYSE: NEM)has decided to defer its capital commitment to build the multi-billion-dollar Yanacocha Sulphide project in Peru, while Freeport-McMoRan (NYSE: FCX) has yet to commit to a mill expansion of its El Abra copper mine in northern Chile.

- Creeping nationalism – Another risk is the potential contagion of nationalism creeping into the mineral sector which has been espoused by Chile and Mexico for their lithium resources. Recent taxation policies in Chile and mining laws in Mexico will also impact foreign direct investment in both countries and put future production of copper, lithium, and silver at risk.

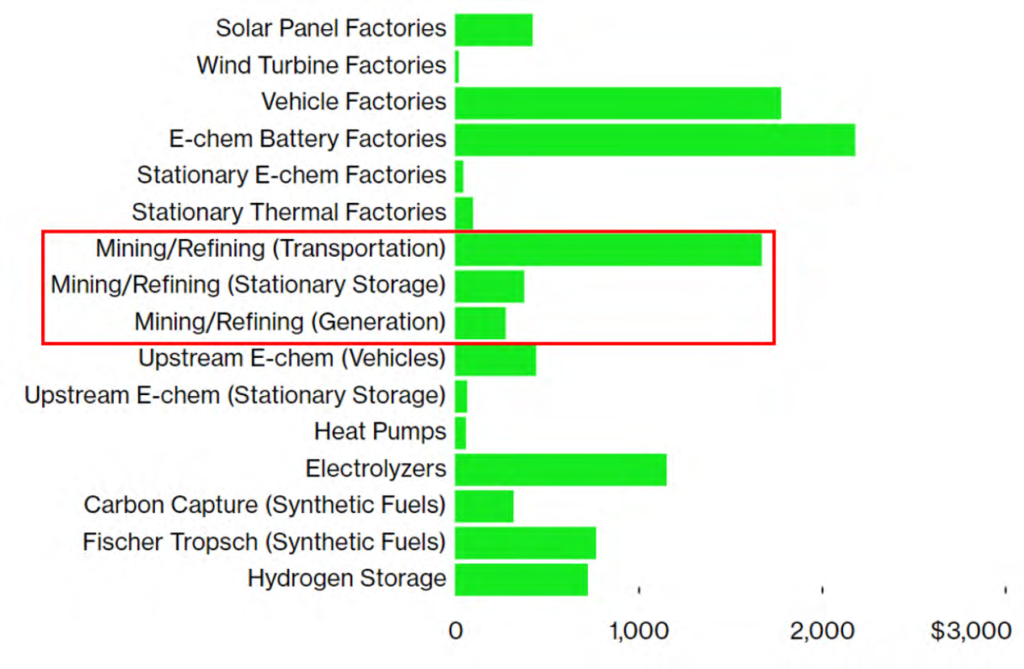

- Infrastructure and funding– The quantum of funds directed by the global mining sector back into its asset base to sustain or expand its production profile has been declining since 2014. Tesla (NASDAQ: TSLA), a large EV manufacturer, estimates that US$502B of mining capital expenditure and an additional US$662B of spending on refining would be needed to produce the nickel, lithium, copper, and other materials for EV battery and clean energy technology. This is not surprising as significant investment in infrastructure will be required to tap into Canada’s endowment of critical minerals, whether it be lithium, nickel, graphite, cobalt, or copper.

For example, the large, low-grade open pit copper-gold development stage Casino project in the Yukon Territory, operated by Western Copper & Gold (NYSE American & TSX: WRN), requires an access road and 130 megawatts (MW) of power to run the 120,000tpd plant. Encouragingly, the Canadian government has committed C$130M in funding to build the road, whose construction has already begun. In addition, the local government is looking at the potential to connect the Yukon to British Columbia’s power grid, with 763km of new power lines, which could supplant the currently proposed LNG power scenario. In addition, the Canada Infrastructure Bank (CIB) plans to support the critical mineral sector by funding projects such as access roads, ports, clean power generation and transmission, and wastewater management facilities. The CIB will target individual investments of over C$100M and its mandate forms part of a long-term investment target of C$5B. However, that may be a drop in the bucket.To support private sector investments, the Canadian government introduced a tax credit of up to 30% of the capital directed to processing for projects that come into commercial production by 2024, which will greatly improve the payback for operators, especially on multi-billion capital projects.

- Development timelines – Another problem is the protracted timeline to advance projects from discovery to commercial production, which ranges up to 20 years for nickel laterite projects. Although the number of years needed to technically de-risk a project through resource definition, metallurgical test work, and infrastructure planning (among other issues), cannot be avoided, lengthier permitting timelines have only added to the burden. For example, a 211-mile access road to the Ambler polymetallic deposit in Alaska, operated in a joint venture between South32 (ASX: S32) and Trilogy Metals (TSX & NYSE American: TMQ), was approved in 2020 after five years of work and consultations by one US administration only to be suspended in early 2022 by another.

- ESG risks – The ability to secure a social licence to operate (SLTO) and access to capital is increasingly linked to a mining project’s carbon footprint. The large projects needed to meet future demand come with larger carbon footprints, especially if they are remote. In addition, some critical minerals have higher intensity carbon emissions per tonne of product due to the large power draws required for processing metals like cobalt, aluminum, and nickel. Eventually, higher prices will lead miners to advance lower-grade projects, whose carbon footprints are more intense due to the larger number of diesel trucks required to move material and the higher power requirements to support the increase in throughput of the processing plants.

- Downstream processing capacity – The majority of mines produce an intermediate product such as a higher-grade concentrate of the mineral that requires further smelting and refining to generate a product that is useable by the final consumer. Over the past two decades, China has been growing its downstream capacity to process several critical minerals, therefore, it is evident that Western countries have a lot of catching up to do, and a focus on the mining sector alone is not enough to secure its supply.

Summary

- A critical mineral is one that underpins the move to carbon-neutral technologies and may be under supply chain threats

- Demand for some critical minerals is expected to grow significantly by 2040 if the energy transition meets expectations

- The market segmentation from China, Russia, and creeping nationalism will constrain the sources of raw and refined materials which may push Canada and Australia to the forefront

- Development timelines for projects are long from discovery to production (15-20 years)

- Quality of the resources from limited sources may suffer

- ESG risks (water usage, carbon footprint) of these development projects may constrain supply further making the road to a carbon-neutral world problematic