In 1980, South African-listed mining equities accounted for nearly 50% of the world market capitalisation for mining companies. An incredible statistic that illustrated the strength of the mining industry in the country. This one country, sitting at the bottom of the African continent with a population of 25 million people, was responsible for a huge $bn value of the world’s listed mining companies. It was a well-earned accomplishment considering the 120+ years that it had taken for the mining industry to grow and evolve in the country.

South Africa offered the world more rich, well-run, and long-life mineral deposits than any country in the world, while the West offered all of the capital needed to develop and mine South Africa’s amazing plethora of mineral deposits. This led to South Africa providing investors with them most diversified and bluest chip dividends and growth of any mining country in the world. All stakeholders – investors, suppliers, the country, its people, and the employees of the mining industry – benefitted from this symbiotic relationship.

In 2003, the greatest commodity boom in the history of the world erupted, with multiple increases in commodity prices. South Africa was able to take part in this boom given its unique stature in international mining investment. However, problems began to arise as the commodity boom masked many of the new unpleasant realities that were occurring in South Africa. The next five years leading up to 2008 saw growing concerns of nationalisation, favouritism towards domestic companies, SOE favouritism, unequal enforcement of laws, and the perception of corruption and illegal activities rapidly and irreversibly taking their toll on the country and its most dynamic industry – mining. Once the boom ended, many of these problems that had been masked by the commodity boom, became more prominent.

As usual, investors were the first to react. Of the $2.2 trillion calculated to have been spent on mergers, acquisitions, and capex on resource projects worldwide from 2002 to 2016, less than 2% made its way into South Africa. The highly risky, unstable and undeveloped DRC received much more than South Africa. Even Zambia, a lesser known mining jurisdiction , received more new mining investment than South Africa did.

So, in today’s market, with 230 countries open for mining investment, South Africa has never had more competition for international funds. It has destroyed its locally grown and world-class mining houses and SOEs, which used to be able to take on mining projects of any size. Mining in South Africa simply cannot grow without foreign capital. Fortunately, South Africa is finally realising this. The government, unions, and even the communities are beginning to come around to this realisation. So, how can funders, investors, and mining companies use the current and future environment in South Africa to guarantee a competitive and safe investment? What will drive investors to invest in South African mining as opposed to investing in other jurisdictions?

Mineral deposits alone won’t draw in the needed investment, no matter how large or rich they are. The government’s policy and legislation also have to be competitive, trustworthy, stable, and easy to understand and implement. Infrastructure plays a huge role too, as does the presence of capable suppliers, and, of course, a motivated and trained labour force. Unions and local communities can often be more of a deterrent than an attraction, so it’s imperative that unions and communities form a strong, enthusiastic relationship before an investment is made.

It is an understatement to say that gold mines with a large capex, high labour costs, and long lead time are not top of mind for investors. Even if Eskom was able to, once again, be the lowest cost , most reliable electricity producer, deep-level gold mines are not attractive unless they can convince potential investors that they have more than enough ability to yield a regular and growing 7% + dividend yield. This is the yield South Africa’s gold industry offered investors for 100 years, at a time when there were far fewer alternative investments and investment destinations available than there are now.

South Africa still possesses 50% of the world’s known gold, but most of it is uneconomically obtainable in the current environment. However, if Durban Deep, Pan African, and Blyvoor Gold can provide above-market returns from their business models and put in a strong performance over the next few years, there is a chance of some kind of a gold mining renaissance in South Africa.

Deep level mines – including gold, platinum, and diamond mines – are not on the radars of most investors in the world today, period. Even base metal deep shaft mines in South Africa, such as Palabora Copper and Okiep Copper’s near 2000m deep Carolusberg Mine , have to offer above- traditional, safer investment yields to get funding. These yields are rarer to obtain today, but not impossible. Northern Platinum (JSE: NHM) and Vedanta Zinc International’s Black Mountain Zinc-Lead Mine are very successful 2000m underground platinum mines, just as the future Venetia Diamond Mine and Palabora Copper (JSE: PAM) third lift mine should be.

Shallower mines, such as chrome, manganese, and coal mines, are much more attractive, but in the current South African environment, even these are viewed with cynicism. The only South African mines or mining projects that currently get an immediate ‘look-see’ from investors and financiers are open pit. It’s actually quite amazing how much funding is available for open pit mines today. Almost none of the excuses given for not investing in underground mines are encountered when canvassing for open pit investment. Obviously, the smaller labour force and Eskom electricity requirements are big attractions, as is the safety aspect. Open pit mines, despite being ten times more environmentally destructive than shallow mines, are the number one choice for investors, and increasingly seem to be governments’ preference as well. This is curious, because aside from employing only one-tenth the amount of labour, open pit mines also often spend 30–40% of their costs on expensive foreign purchases (i.e., equipment, supplies, specialists, and diesel).

Adding all of this up, what does it mean for investors today?

- Most mining investors typically know what they are doing and why. Investors in mining know the industry and the country.

- Most mining investors who put their money into South Africa (+95%) do it via large market cap shares. These are much less risky than small-listed equities, start-ups, and unlisted shares.

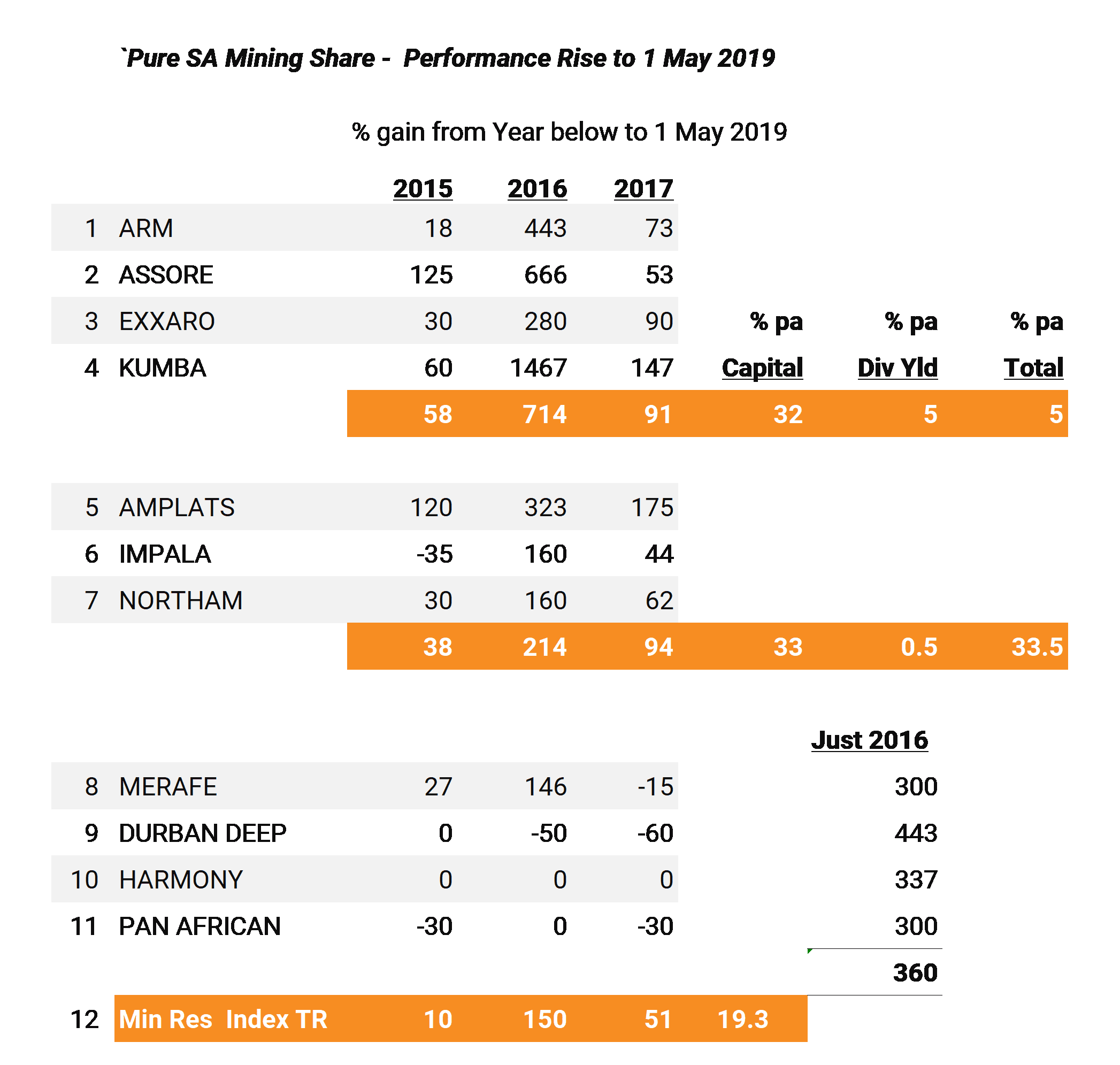

Figure 1. (previous page) shows the main ‘pure’ South African mining shares (excluding Billiton, Glencore and Anglo). These shares basically perform on the back of their underlying commodity price, but also on how well they manage their environment. In this respect, we can assume that;

- Great assets certainly assist companies in managing their environment, including commodity price, government policy and legislation, unions, communities, and Eskom, among other things.

- The more mature and developed the company and its management, the better it can manage everything.

- Unlisted shares, start-ups, small caps (small balance sheets), and single product producers can be risky.

Years ago, mining houses were created in a natural, evolutionary way. There was great investment return in starting up a mine from scratch and then listing it. But it took a lot of work, time, and money to stand up against the various risks in the environment. All of those risks have massively increased over time, so a mining house balance sheet and support system is now more essential than ever. Mining has never been a business for small players. The plethora of requirements is too large, especially nowadays with the necessity of working with governments, unions, communities, environmental groups, and – in South Africa’s case – Eskom and punitive, continually-changing laws (i.e, MPRDA and BEE).

The odds are stacked against start-up mines in South Africa. The privately-operated ones remain way below the radar, making it near-impossible for most investors to get involved, yet alone achieve transparency or liquidity. It is also much harder and more expensive to obtain working capital and finance for small-cap and unlisted shares than for listed and largecap mining shares.

Investors must really know what they’re doing and what they want to stick with. They will want to stick with the

listed and established South African mining equities, especially if they’re playing the metal price game (as opposed to indexing, which is safest of all) or speculative investing looking for high increases from bringing a

start up to production and listing.

Mining always has been, and always will be, cyclical. Use that fact to time your investments accordingly and you will achieve great outperformance!