With a year-to-date return of close to 30% up to the beginning of September, including a short spike beyond the USD 2,000-mark for the first time in history, gold has performed exceptionally well in 2020. And, as we will argue below, gold has not reached the end of the rope. In fact, the 2020s are set to become a golden decade.

COVID-19 is not the reason for our optimism regarding gold. The pandemic is just a catalyst, speeding up and intensifying developments that have been supportive of gold for quite a while, such as global indebtedness and low interest rates. Also, we must not forget that the global economy was already cooling down before the COVID-19 lockdowns hit economies around the world.

A series of monetary tricks on the way

Due to the coronavirus crisis, monetary and fiscal policymakers around the world are feverishly seeking new ways to stimulate the economy. Conventional quantitative easing is still part of the standard repertoire of central banks. Deflationary tendencies are once again hitting the economy with full force in the current recession. In the past, deflation could be only partially warded off by central bank purchases of securities. Spurred by the zero-interest rate policy that is now widespread around the world, discussions have been ongoing for years as to what the next stage of stimulus will look like. Leading the race are proposals such as deeply negative interest rates, yield curve control, or the implementation of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT).

Whether the new monetary and fiscal policy measures are implemented in the form of negative interest rates, yield curve control, or MMT, the bottom line is that they are all old wine in new skins. As so often happens in history, the financing of a deficit is inevitably done by devaluing the currency.

But when will inflation (re)appear? Within what we call monetary tectonics, the tensions between the two forces of inflation and deflation are currently higher than ever before. Over the course of the global lockdown, the velocity of monetary circulation has fallen significantly. Closed shops, but more importantly the uncertainty caused by the pandemic, have led to a great decline in consumption and increased savings behavior among a large part of the population. All of this has had a strong deflationary effect – at least temporarily.

“THE 2020s WILL GO DOWN IN INVESTMENT HISTORY AS A GOLDEN DECADE BECAUSE GOLD WILL BE THE BIG BENEFICIARY OF THE CURRENT ECONOMIC, POLITICAL, AND GENERAL SYSTEMIC CHALLENGES”

The central banks are countering with their gigantic injections of liquidity. Therefore, we are convinced that we will soon face a decisive fork in the road and disinflationary pressures will (have to) be broken. Forty years ago, it was essential in the US to kill inflation at all costs. Today we are at the other extreme: it is essential to do whatever it takes to prevent falling consumer prices. The disinflationary side still seems to have the upper hand. If none of the monetary tricks described above have the desired effect, the last resort for central bankers is still helicopter money.

In any case, inflation will be a key issue for investment decisions during this decade. A rising inflation dynamic would be good news for inflation-sensitive investments such as gold, commodities, and mining stocks. On the other hand, leaving the current phase of low inflation could prove to be a bitter pain-trade for investors, especially when the 40-year party on the bond markets comes to an end and the traditionally negative correlation between equities and bonds suddenly turns positive.

Our central conclusion in this year’s In Gold We Trust report is that the 2020s will go down in investment history as a golden decade because gold will be the big beneficiary of the current economic, political, and general systemic challenges.

Quo vadis, aurum?

As gold investors, we are naturally very interested in the question of how the gold price might develop over the course of the coming golden decade. We will now look at how to approach it using a proprietary valuation model.

The valuation of gold is fundamentally different from the valuation of cash flow-generating assets. The discounted cash flow models commonly used in finance are not applicable to gold. After all, in a fiat monetary system the price of gold rises in the long term to the same extent as the money supply, because the existing gold supply is almost constant while the money supply is permanently inflated.

We use two parameters to calculate the price target: money supply developments and the implicit gold coverage ratio. Since the US dollar is still the world’s reserve currency and has the strongest influence on the price of gold, we analyze the data for the US dollar and obtain a price target in US dollars.

The future development of the money supply

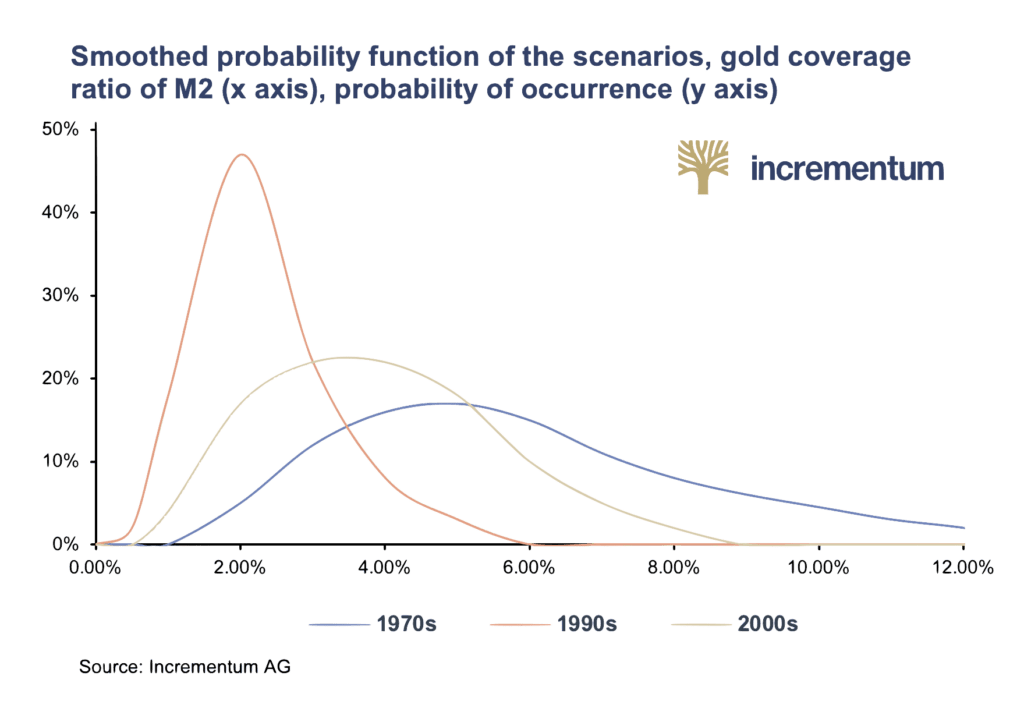

We have drawn up three scenarios for the growth rate of the money supply in the coming decade. We use the money aggregate M2 because it is less volatile than narrower monetary aggregates like the monetary base, MZM, and M1. We have used historical M2 growth rates from different decades as potential growth rates and have provided these scenarios with an estimate of their probability of occurrence.

- M2 growth rate in a decade with high growth (1970s): 9.7% p. a.; probability of occurrence: 15%

- M2 growth rate in a decade with low growth (1990s): 3.9% p. a.; probability of occurrence 5%

- M2 growth rate in a decade with average growth (2000s): 6.3% p. a.; probability of occurrence 80%

The implicit gold coverage ratio

The implicit gold coverage of a currency is calculated by valuing the central bank’s gold reserves at the current gold price and relating them to the money supply. Over the long term, the gold coverage of the money stock M2 moves around 3.3%. It is clear that in times of declining confidence in the monetary system, the gold coverage ratio increases significantly. This was the case in the stagflation of the 1970s and the Great Financial Crisis of 2007–2009 and its subsequent sharp recession.

For the three growth scenarios for the money stock M2 presented above, we have modelled a distribution function based on historical data.

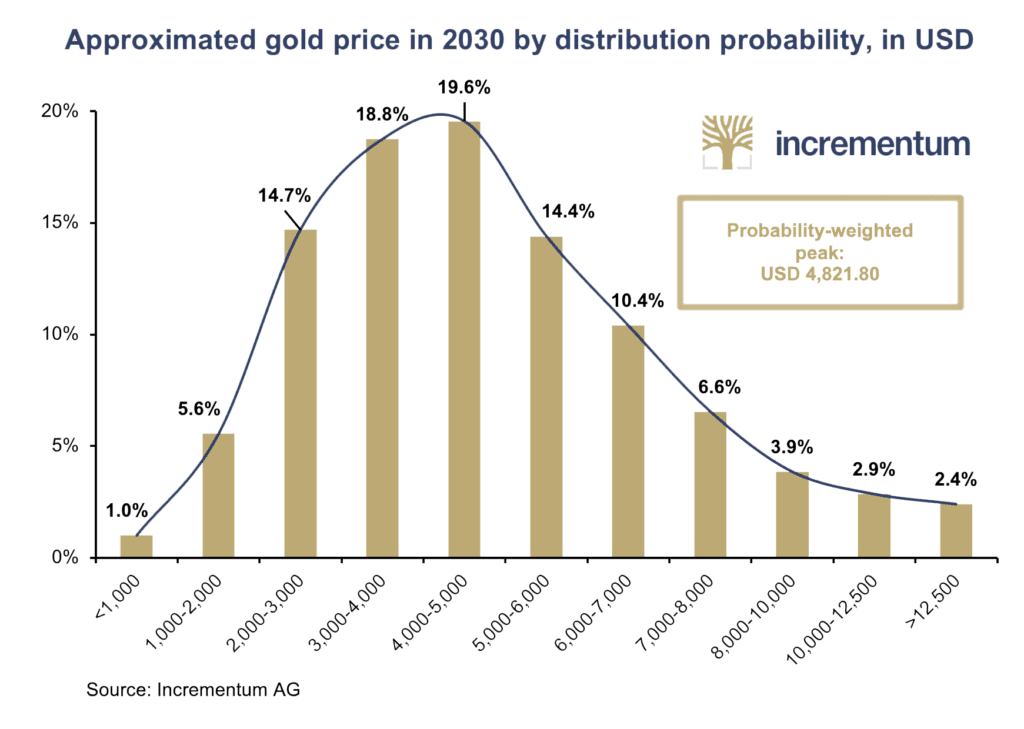

If we now calculate a cumulative distribution function across all scenarios, the following picture emerges:

Our expectation for the gold price at the end of the decade is around USD 4,800.

The distribution is clearly skewed to the right. This means that significantly higher prices are far more likely than lower ones. Of course, quantitative models of this kind always have a certain degree of fuzziness. However, we believe that we have taken a conservative approach to calibrating the scenarios. Due to the unique global debt situation described in detail in this year’s In Gold We Trust report, growth figures for M2 in the decade that has just begun are not implausible at the same level as in the 1970s. In this case the model suggests a gold price of USD 8,900 by 2030.