As a metals merchant and financier long dedicated to helping mining companies, industrial end users, and recycling companies navigate the precious metals markets, Auramet keeps track of the most current information on the supply, demand, and cost of the PGMs. In 2018, we purchased more than 2.5 million ounces of PGMs (all of which were eventually consumed in industrial applications across three continents). Given that 2019 saw a significant increase in both PGM prices and volatility, it is even more meaningful that our clients understand not only what drives the current market conditions, but what can be expected going forward. This article will address the future of the three most prominent PGMs (palladium, platinum, and rhodium), focusing specifically on how the demand for each metal will be influenced by the gradual shift of the global automobile market away from internal combustion engines and towards motors solely powered by electric batteries.

Palladium and Rhodium

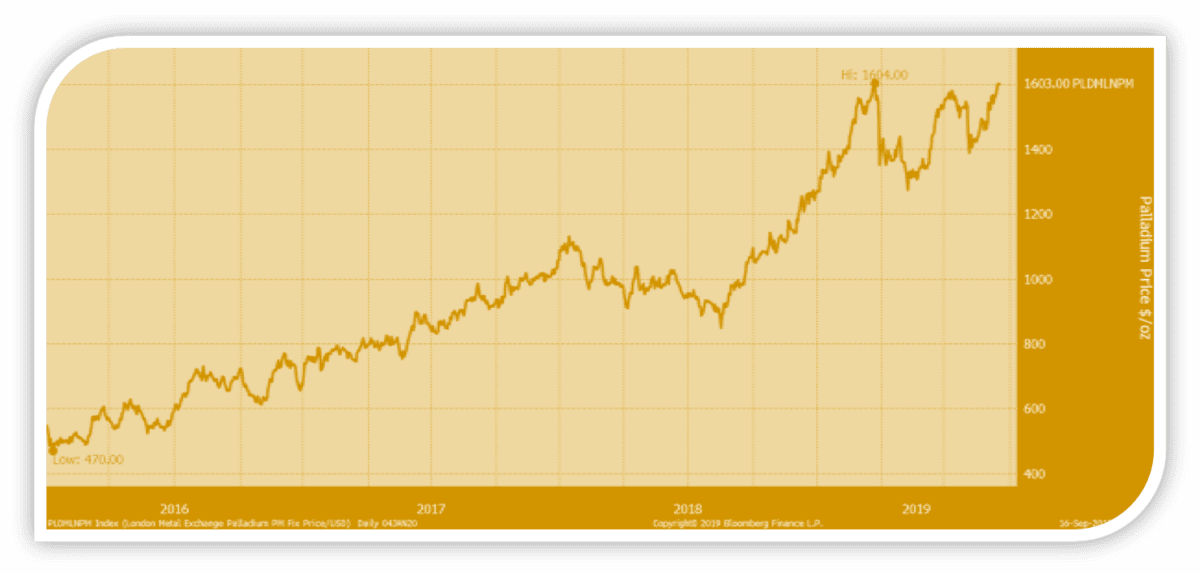

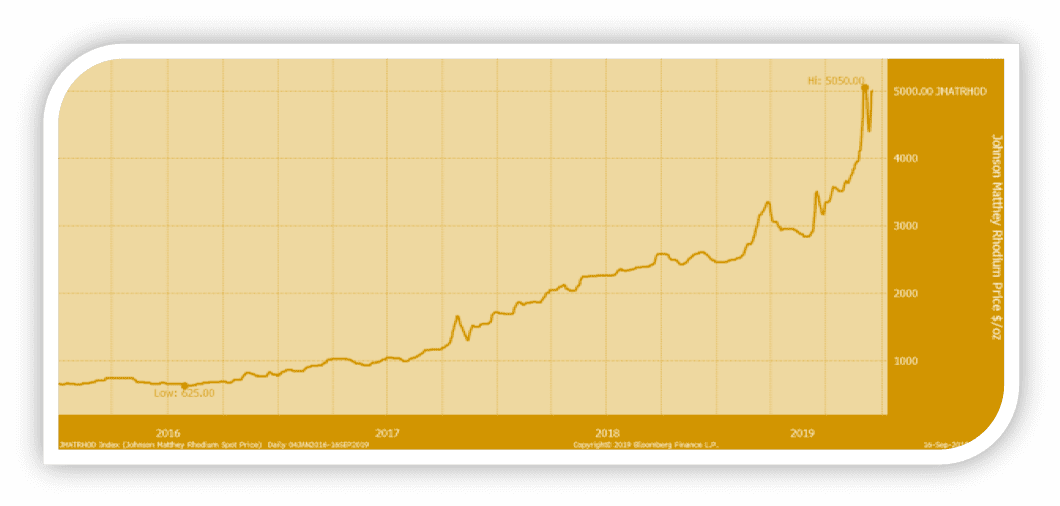

Less than a year ago, palladium became more expensive than gold for the first time in sixteen years. The price tripled from the start of 2016 to the spring of 2019 and remains near historical highs at the time of this writing. Given that rhodium has experienced an even greater surge in price over the past four years (it doubled during the first nine months of 2019 alone) and like palladium, has an oversized dependence on the automobile industry, our main focus will be on these two metals.

Those who closely follow the physical demand for palladium and rhodium will note the curious dichotomy between its outstanding near-term outlook and less certain long-term future. Strongly impacted by the major environmental problems confronting the world today, demand is expected to remain robust, but only as long as the combustion engine remains king of the road. What makes studying the two metals so compelling is trying to gauge how long that will continue.

The volatile dynamics that help govern the near, medium and long-term future of the two metals stem from their primary use as key components in autocatalysts for gasoline engines, with the aim to reduce harmful emissions (85 percent of all palladium and rhodium demand comes from the manufacture of such catalysts). As automakers are being forced to comply with ever-tightening emission standards around the world (particularly in Europe and China), the short term demand for both metals continues to rise even as global auto production begins to tail off (palladium and rhodium demand for autocatalysts is expected to increase by 8.9% and 10.4% respectively in 2019 according to the JM PGM Market Report). However, just as this trend continues to move demand in one direction, ongoing concerns about global warming and the consequent move towards zero-emission electric vehicles should ultimately drive it the other way. How soon, how fast, and how far the demand for the two metals will fall depends on how long conventional hybrid vehicles (HEVs) and plug-in hybrid vehicles (PHEVs) continue to be produced. This will be influenced by government policies in China, the US, and Europe, as well as by the

collective whim of automobile producers and consumers around the world.

As an active liquidity and hedge provider to mining companies, recyclers, catalyst manufacturers, and auto companies, Auramet is in daily contact with these and other PGM stakeholders. Although few deny that the era of the combustion engine will eventually come to an end, there is little consensus as to when that will happen and how it will play out in the interim. If the global pace towards all-electric vehicles is rapid, the demand for both palladium and rhodium can be expected to drop proportionally. But the path could be more winding; rhodiumbearing catalysts and hybrid vehicles that still require palladium may gain in popularity as the infrastructure for zero-emission electric vehicles struggles to establish itself.

Given the vast number of factors that could shape the future of the automobile, the viewpoints of industry experts vary significantly and change often. While making predictions on any new technology is difficult, we hope to shed some light on the topic from the perspective of a leading precious metals merchant. We’ll start by discussing the status of the two largest electric vehicle markets in the world: China and the United States. These two countries currently represent 75% of the market for electric vehicles and will continue to define the industry’s future.

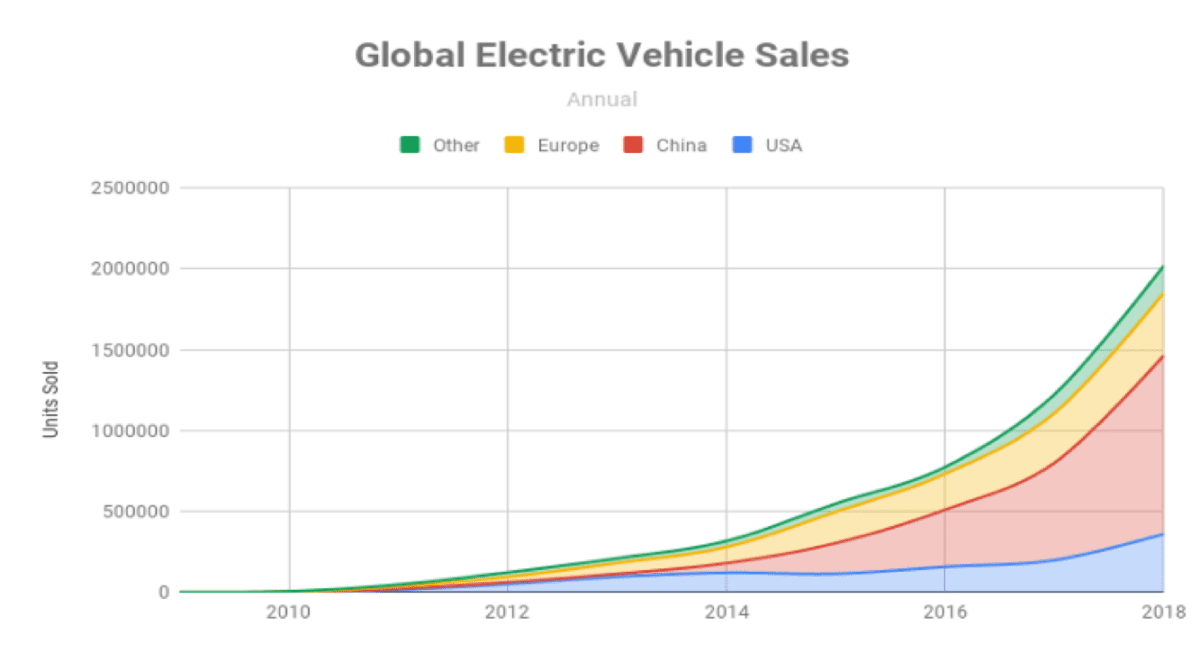

During 2018, electric vehicles (EVs), which include both battery electric vehicles (BEVs), conventional hybrids, and plug-in hybrids, accounted for 2.1% of the total cars sold around the world. Nearly 70% of these sales (or just under 1.5% of total cars sold) were emission-free BEVs. While PGM miners would be forgiven for thinking that these percentages hardly present a major threat, the more pessimistic of them would point out that the percentage is growing quickly (the total number of EVs sold globally last year was 64% higher than in 2017) and is expected to accelerate even faster (Bloomberg New Energy Finance predicts the total number of EVs sold will rise to 10 million by 2025 and 56 million – or 57% of new car sales – within twenty years).

While these estimates hint at an uncertain future for palladium and rhodium demand, the pessimists need not panic. Even after BEVs become equal to or cheaper than gas burning ones, much still stands in the way of an all-electric vehicle revolution taking hold. Putting aside the formidable challenge of upending a gas engine automobile culture that has flourished for over a century, two key hurdles rise above the rest: battery efficiency and ease of charging. Although technological developments should continue to improve battery efficiency, BEVs in China and the US have an average range today of just 124 and 248 miles respectively (Columbia/SIPA Center on Global Energy Policy). Until such ranges are extended, many consumers will opt for hybrids to eliminate the stress of being stranded somewhere along the road.

As for creating a satisfactory charging experience, this remains the principal challenge for EV producers on both sides of the world. For starters, engineers have yet to create a battery that can be recharged quickly and efficiently. In the best conditions, it currently takes about an hour to fully charge the battery of a BEV, and that assumes that (a) a Level 3 charger (the strongest and least available of chargers) is available, (b) one does not have to wait for a charger to be free, and (c) other cars are not charging at the same station (which lengthens the charging times for all cars at that station). Today, the typical charging experience tests the patience of even the most ardent environmentalist. Although progress continues to be made (Porsche recently announced that they are launching a battery that can be charged from 5% to 80% in less than 23 minutes), much work needs to be done.

As briefly mentioned above, charger availability is also a problem. Even if potential EV buyers in America can come to terms with slow charging times, they must factor in the shortage of chargers. When they do, they might pause to consider the following:

I. Public charging stations are scarce (just over 20,000 across the US with an average of approximately 3½ connectors according the Department of Energy), they often operate with just a single source of power (slowing down the process), and less than 16% of them offer fastcharging (defined as providing approximately 60-80 miles of range for every 20 minutes of charging)

II. Charging stations remain uncommon in apartment buildings (where more than 25% of the US population lives) and workplaces (85% of American workers commute by car)

III. It has recently been reported that there are well-funded groups backed by oil interests waging aggressive state-by-state campaigns to disrupt all efforts by utilities to build charging stations

In an era when the choice of a car for a typical American can be influenced by something as trivial as a cup holder, slow charging times and the lack of a proper charging infrastructure need to be fully addressed before BEVs can take over the US market.

Although China has a more advanced infrastructure with over 70,000 public charging stations, until the experience of recharging a battery more closely resembles refilling a tank, the growth of BEVs will be restricted there as well (although the Chinese government can move the EV dial more quickly if it chooses to do so).

Can the EV charging infrastructures in the US and China stay ahead of the potential pace of BEV sales? If it does, it will be difficult to prevent the eventual demise of the combustion engine which, in turn, would substantially reduce demand for palladium and platinum (unless new uses for the metals are discovered). But it seems unlikely this will happen anytime soon, so hybrids will remain an attractive option for consumers around the world, and catalysts bearing palladium and rhodium will continued to be manufactured for them.

Given the position we occupy in the global precious metals industry, the arc of Auramet’s focus on the future leans naturally towards the short-term. But, if Bill Gates was correct about technological change when he commented that “we always overestimate the change that will occur in the next two years and underestimate the change that will occur in the next ten”, it behooves us to try to understand and articulate to our clients how major transformations in the automobile industry might influence the PGM markets.

Brief Comment on Platinum

The medium to long-term threat for platinum due to BEVs is also high, but while 85% of palladium and rhodium demand went into the production of autocatalysts in 2018, less than 39% of platinum’s did (JM PGM Market Report, May 2019). Platinum is the PGM used for catalysts in diesel-burning vehicles (although quantities of it are also used for gasoline engines). Due to the collapse in sales of diesel vehicles in Europe following “Dieselgate” (the prosecution of Volkswagen in the US for gaming the emissions testing process), demand for platinum fell rapidly. Today’s platinum prices, nearly 50% lower than five years ago, hover just above their ten-year lows. Although there are some expectations that the continued strength of palladium prices will cause gasoline engine catalyst producers to switch over to platinum (as they have done in the past), most experts believe that only when the price of palladium doubles that of platinum will substitution take place to any material degree. Even then, because of its stability in the higher temperatures of gasoline burning engines, palladium cannot be replaced on a one-for-one basis by platinum.

One potentially huge boon to platinum demand is fuel-cell technology. Among the PGMs, platinum has the most to gain if this alternative method of powering cars and machines moves forward (fuelcell cars currently require between 5-10 times the amount of platinum that the average diesel automobile catalyst does, but this is expected to fall as technology progresses). However, whether and when that happens remains uncertain for many reasons that are not in the purview of this article to detail. If there is a positive impact on the demand for platinum from fuel cells, it is unlikely to occur within the next twenty years. Until then, platinum prices will continue to be dictated by demands made on the metal by jewelers, investors, manufacturers of catalysts for diesel engines, and other assorted industries.|