Periodically, investors, mining executives, regulators, and others, go through an introspective phase, stopping to ask about the accuracy and reliability of the supply and demand data on which they base their decisions. One such period has emerged this year. As a result, CPM has had several requests for information related to the wide disparities in estimates of gold, silver, and platinum group metals (PGM) supply and demand among groups that publish such data.

At times, these markets are overrun by inaccurate information provided for free by groups selling or marketing the metals. Banks and brokers then rely on these free data sources. This typically leads to less profitable investment decisions.

Precious metals and other commodities are secretive markets, with information and statistics on secondary supply, fabrication demand, and inventories treated as corporate secrets with no regulatory obligations for disclosure. Publicly listed mining companies make data available because they have an economic interest in informing investors and face regulations requiring such information be disclosed.

The reality is that, in all commodities markets, measuring fabrication demand directly is nearly impossible, so market analysis often relies on ‘apparent demand’ estimated as the differences between newly produced supply and changes in inventories, adjusted for net imports or exports.

This is true even in the largest, most economically important and closest monitored commodity market: petroleum. Since the first oil embargo and the sharp increase in petroleum prices in 1973-1974, most governments have created energy departments and ministries to monitor their domestic oil markets. They do not all attempt to measure how much petroleum is being used. All of them rely on apparent demand calculations.

The use of fundamental data

Having accurate assessments of how much metal is coming from mines and scrap, and how much is being used by fabricators or hoarded by investors (or others), is critical to being able to make better investment decisions, whether it is to buy metal as an investor or to spend many years and billions of dollars building a new mine, smelter, or refinery.The question thus arises as to which statistics one should use for making investment decisions; which set of disparate data more accurately estimates past total supply including scrap, fabrication demand, and other segments of the market; and which set of projected supply and demand data is more reliable.

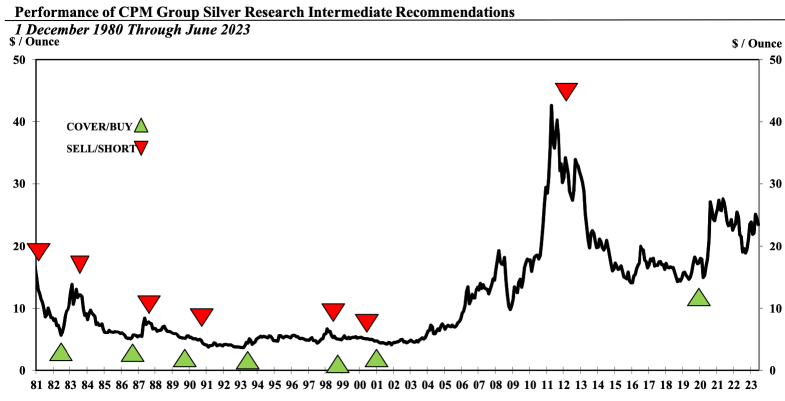

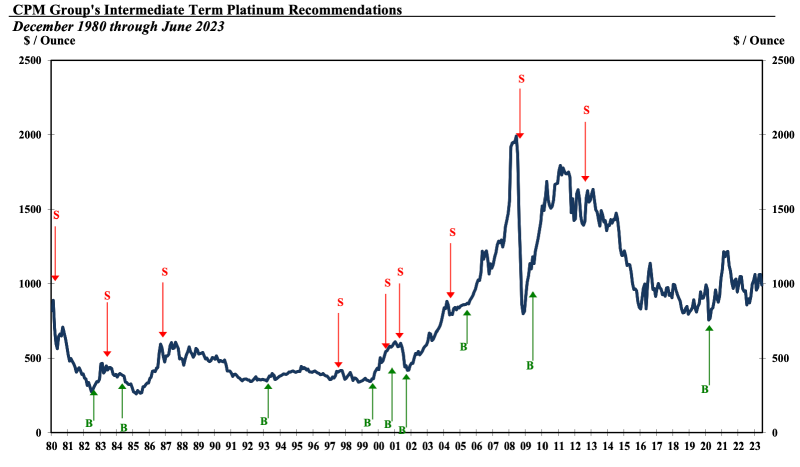

One measure of the accuracy of CPM Group’s estimates and projections lies in the fact that, since 1980, CPM has had an unrivaled track record of projecting the intermediate term (one to three years) trajectory of gold, silver, PGMs, copper, molybdenum, cobalt, lithium, uranium, tungsten, vanadium, titanium, and other metals, as well as oil and natural gas.

These projections are built upon our fundamental supply and demand statistics. If our data was wrong, one would expect the price projections based on the statistics to be wrong. Conversely, if the price projections have been better than others, (as has been the case), it serves as evidence that our fundamental statistics may be close to accurate.

Having accurate assessments of how much metal is coming from mines and scrap, and how much is being used by fabricators or hoarded by investors or others, is critical to being able to make better investment decisions

Measuring fabrication demand and secondary recovery

CPM has been in the business of estimating past, present, and projecting future supply and demand for gold, silver, PGMs, high purity manganese, molybdenum, and a host of other largely opaque commodities since before its inception, going back to the 1970s at McGraw Hill, J. Aron, and Goldman Sachs, and at CPM Group, since 1986.

It is difficult and intense work. We befriend refiners, traders, fabricators, investors, governments, and others around the world, earning their trust and swapping insights and estimates on scrap refining, fabrication demand, and more.

Investment demand

Investment demand for gold, silver, PGMs, and other physical commodities is impossible to measure directly. Investors buying precious metals have a strong impetus toward privacy and secrecy. These are attributes of these metals that investors seek.

Platinum and PGM investors, perhaps, have different rationales for their secrecy and privacy imperatives than gold and silver investors. The platinum market is very small compared to gold and silver, and there are very few major market participants. This makes it more difficult to buy large volumes of PGMs undetected, and to hold on to them undetected.

Selling them presents even greater problems. When it comes time to sell the metals, one is beholden to those dealers one has dealt with.

These issues have led some significant PGM investors to employ CPM, for our experience and expertise, our knowledge of and ability to exact reasonable prices, and for the added layer of privacy it provides. This gives CPM added insights into investment demand.

Measuring investment demand is limited by the fact that there are a few quantifiable measures, such as national Mint reports on how much metal they used and sold in official coins, and (since their creation in the 2000s), changes in exchange traded fund holdings. CPM uses some other metrics that we do not make public.

Most investment demand is in bullion form, away from ETFs, including both bars and (surprising to many in the platinum market) sponge or powdered platinum. These purchases and sales go unreported. As a result, investment demand is best measured ‘by its shadows.’

There are indications of when investors are buying and selling metal, however. One is the price of platinum.

- When the platinum market ran large surpluses from the late 1980s into the mid-1990s, those excess supplies of newly refined metal were bought by South African platinum producers and their marketing agents through 1993. This was apparent by the lack of rising prices. Producers and refiners, as somewhat reluctant buyers of excess metal in a surplus market, tend not to bid up the price.

- In contrast, when investors were the buyers of the large surpluses from 2001 through 2007, it was apparent in the rising price of platinum. Investors bid prices higher

Measuring annual surpluses or deficits of newly refined metal entering the market relative to fabrication demand is critical to developing an accurate opinion of investment demand trends. One must exclude hypothetical estimates of investment demand from such market balance calculations to have a clear vision of the health of the market and the current investor posture at any given time.