On 16 March 2023, the European Commission (EU Commission) published its Critical Raw Materials Act proposal as a key plank to its push to achieving its green energy targets.

The commission’s executive vice-president, Valdis Dombrovskis, said the proposal recognizes the indispensable role played by certain critical raw materials in achieving the EU’s climate neutrality goals across a wide range of sectors such as renewable energy, healthcare, and defence, and proceeded to identify a list of critical and strategic raw materials before laying down the framework for the EU’s sustainable access to these.

Notably, the proposal sets out four targets to be achieved by 2030, in relation to extraction, processing, and recycling of critical materials in the EU.

It also creates a framework to promote “strategic projects,” including support with financing, offtake agreements, and administrative processes, as well as a requirement for member states to submit exploration programmes for critical raw materials.

The EU Commission says sustainability and circularity are at the core of the proposal, with an obligation to increase recycling and reuse of critical materials, and environmental and social compliance being key criteria to determine whether projects are eligible to be awarded strategic project status.

The proposal also aims to facilitate joint procurement of strategic raw materials through the creation of a system to match interested parties consuming these materials with authorities responsible for stocks of strategic raw materials and enabling them to jointly negotiate purchase terms.

Dombrovskis said the proposed legislation is aimed at securing access for the EU to a sustainable supply of critical minerals.

“The EU is looking to meet its target of net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050 and reduce its dependence on non-EU countries for the sourcing and refining of critical minerals. To make this happen, we need critical raw materials – or CRMs – and here, our needs are very clear. Demand for critical raw materials will grow many times over the next decade. Let me give some specific examples.”

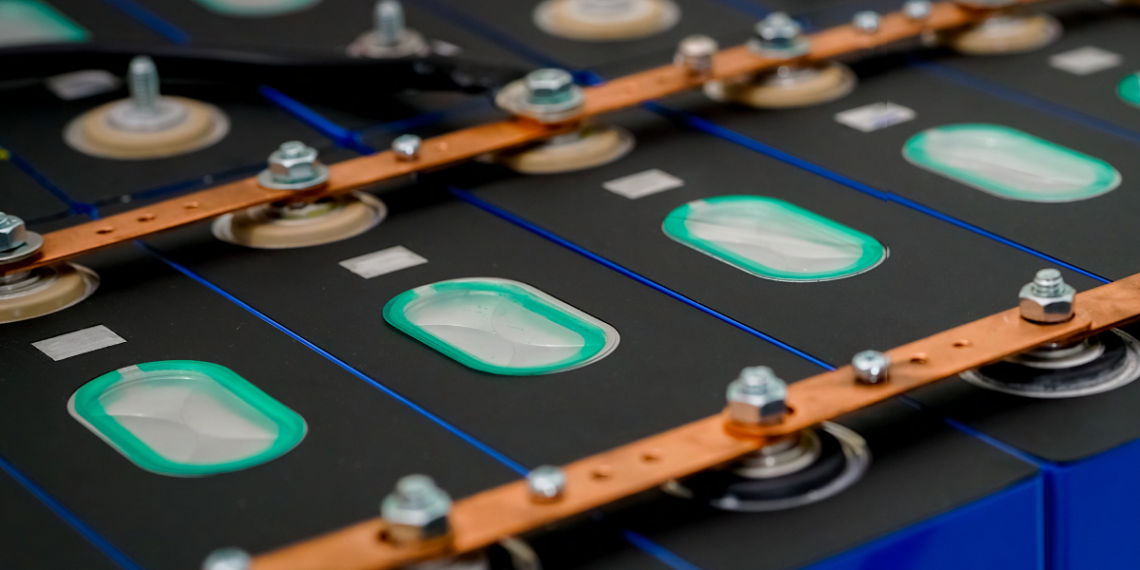

“For our desired level of wind turbine production, demand for rare earth metals is expected to be five to six times higher by 2030 and six to seven times higher by 2050. Take electric vehicle (EV) batteries, demand for lithium is expected to be 12 times greater by 2030 and 21 times higher by 2050.”

“However, we are not a resource-rich continent. Our domestic supply will provide only a fraction of the critical raw materials we need.”

“For many of the critical raw materials, we depend heavily on a small pool of partners, sometimes, just one partner. This is not a stable nor reliable way to build the industries of the future.”

“So, we urgently need to diversify. Today’s communication aims to maximize our ability to access, process, refine, recycle, and deploy critical raw materials. Our goal is that by 2030, our capacity should reach at least 10% of domestic demand for mining and extraction, at least 40% for processing and refining, and at least 15% for recycling.”

Dombrovskis highlighted the EU’s inability to match its requirements with mining extraction.

“10% domestic capacity means that 90% will somehow need to be sourced outside the EU. We simply don’t have the resources to meet our needs. Additionally, the production chains for CRMs are global and complex. So, we need to use our traditional strength of building relationships based on openness, trust, mutual gain, and clearly defined rules.”

“We know that many resource-rich countries are keen to attract partners to develop their own critical raw materials value chains sustainably. The EU can help – with its institutional know-how and investment power to support capacity-building. This can also promote better product quality, more innovation, and reduce costs.”

“As a result, our partner countries will be in a strong position to move up the value chain themselves. We plan to use the Global Gateway to assist them in developing their own extraction and processing capacities, including skills development.”

Trade Agreements and the Critical Raw Materials Club

Dombrovskis said the EU is already building critical raw materials cooperation into existing or upcoming free trade agreements.

“We recently concluded agreements, for example, with New Zealand and Chile, which have dedicated raw materials chapters. We are working on a free trade agreement with Australia, which will also have a raw materials chapter as part of this trade deal. We have already signed strategic partnerships with Canada, Kazakhstan, Namibia, and Ukraine.”

“And we are working to expand our network of critical raw materials partnerships in our region – with Norway and Greenland, and further afield, with the Democratic Republic of Congo and Rwanda, in Latin America with Argentina, just to give some examples. We will create a ‘Critical Raw Materials Club’ for all interested countries to strengthen global supply chains – bringing together consuming and resource-rich countries for mutually beneficial cooperation.”

EV demand

The race to shore up European critical minerals supplies has been highlighted in recent studies, which found that Europe will become the world’s biggest EV market from 2030, overtaking the US and China, as European EV registrations accelerate, and sales exceed 70% of the market.

A European Automobile Manufacturers’ Association (ACEA) study found that, while China is currently ahead of Europe and the US in the electrification of the car market, the European market will rebound in 2025 and take the lead again on the other world regions by 2030.

Proposal timing

The EU proposal must still be discussed and agreed by the EU Parliament and the EU Council before it enters into force, which means its content is still subject to change. The EU Commission has not given any indications on the timing of when such discussions with the parliament and council of the EU are expected to take place.

The proposal will be adopted as an EU regulation (as opposed to a directive), which means it will have direct effect in the EU as soon as it enters into force, without the need for EU member states to enact legislation to implement its provisions at the national level.

However, some of its provisions are quite broad and further detailed legislation may be required in practice.