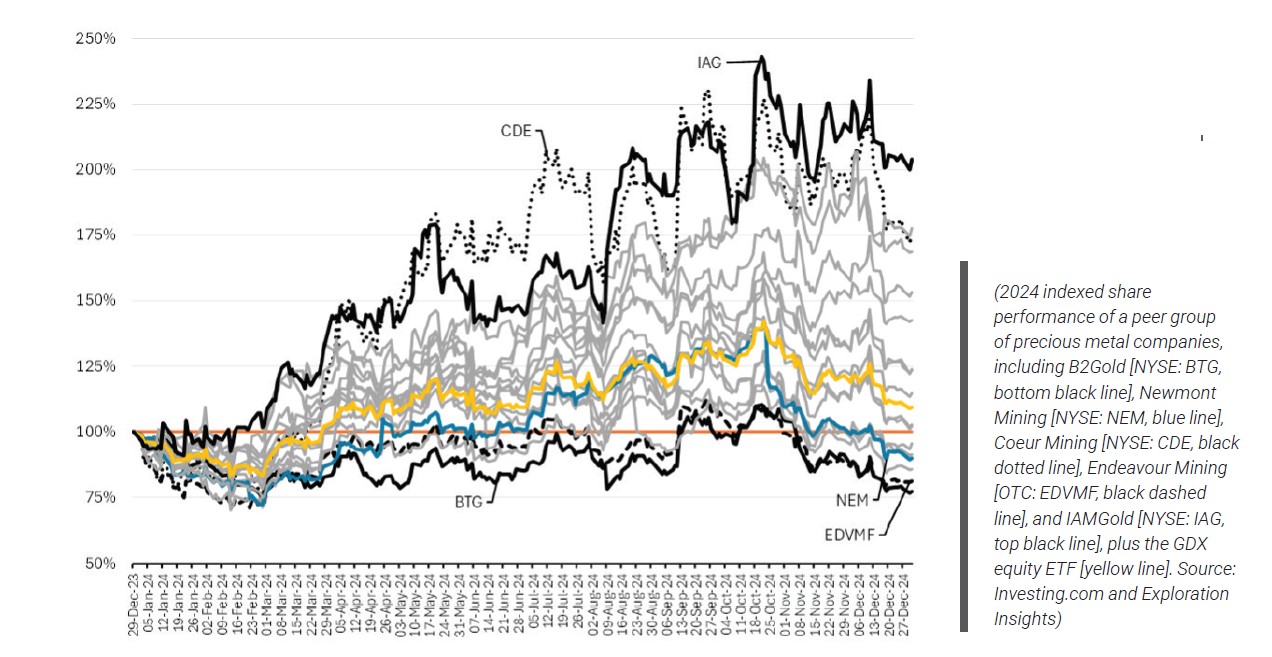

Despite gold being among the best-performing asset classes in 2024, the gold equity exchange-traded funds (ETFs), for major precious metal producers, (GDXJ +13% and GDX +9%) did not deliver the expected leverage.

Among a peer group of 17 gold mining companies, IAMGold Corp. (NYSE: IAG) offered the most leverage to the gold price last year. In August 2024, the high-cost precious metal producer brought into commercial production a large open pit mine (Côté Gold) in northern Ontario after closing a significant bought-deal financing (US$300M) in May to acquire a larger stake in the project, partly to diversify its portfolio away from West Africa. At the end of 2020, it had sold its stake in the Sadiola gold mine in Mali.

Before the Côté Gold mine ramp-up, the company’s largest operation was the Essakane mine (90% IAG) in Burkina Faso — estimated to generate between 380,000 and 410,000oz of gold at an all-in sustaining cost (AISC) of up to US$1,675/oz. According to its 2024 share price returns, the diversification strategy seems to have successfully offset security issues in Burkina Faso and creeping nationalism in Mali.

On the other end, B2Gold (NYSE: BTG), was the group’s worst performer, mainly due to challenges in constructing the Goose Lake gold project in Nunavut, Canada, and operational setbacks at the Fekola gold mine complex (90%) in Mali, triggered by changes to the mining code. The challenges faced at Fekola resulted in a US$206M impairment in 2023 and an additional US$194M loss in the first half of 2024. The next worst performer was Endeavour Mining (LSE: EDV), which also has significant exposure to West Africa.

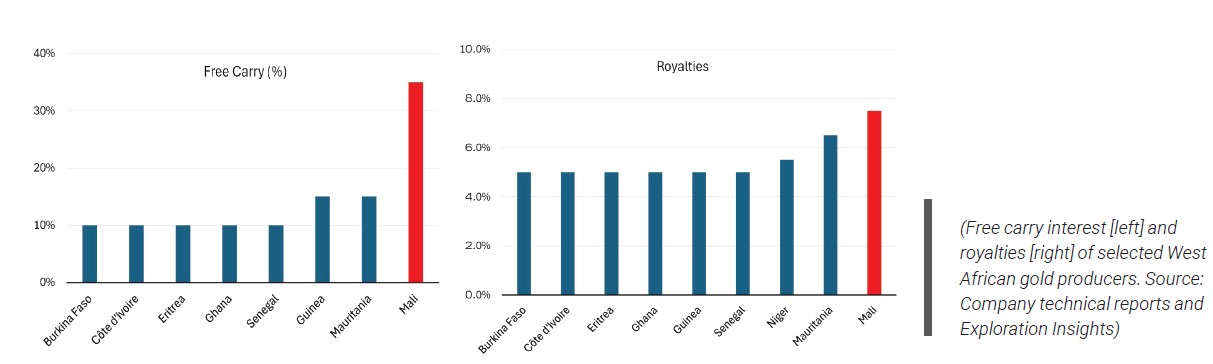

Major producers such as Barrick Gold (NYSE: GOLD) are not immune to Mali’s government threats to impose the old mining code, which includes a 20% increase in government ownership to 35% and royalties up to 7.5% (>US$1,500/oz). An arrest warrant has recently been issued for the CEO for unpaid taxes and royalties that have been estimated to be US$512M.

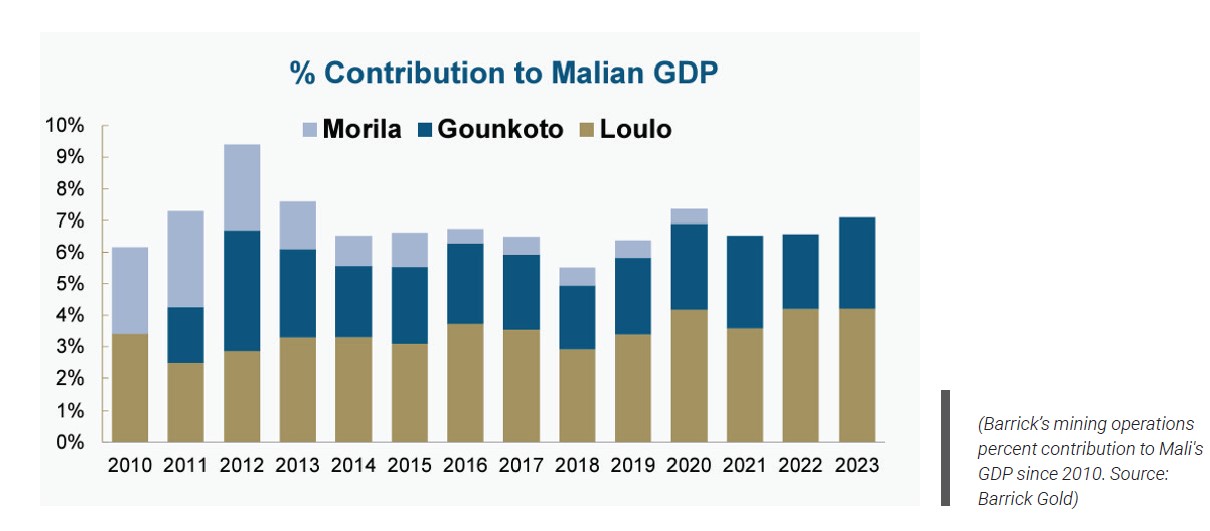

Barrick argues that its mining operations contributed about 7% of Mali’s GDP in 2023, and it has invested over US$10B in the country since 1996. Nonetheless, gold shipments from its Loulo-Gounkoto mining complex (~700Koz/y) have been blocked, and employees have been imprisoned, forcing the major precious metal miner to consider suspending operations, which employ 8,000 people (97% from Mali).

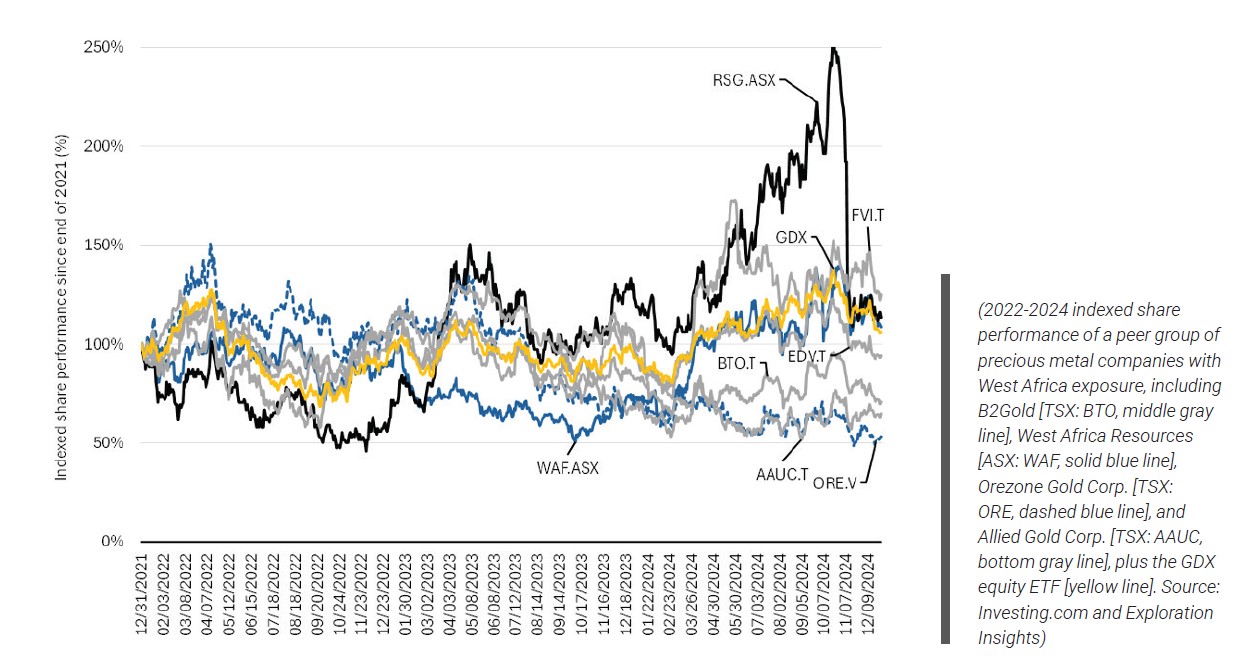

For most of 2024, Resolute Mining (ASX: RSG), another company with significant exposure to West Africa, outperformed a group of seven companies with operating assets in the region until news broke out in November that Mr. Holohan — its managing director — and two other executives had been detained over unpaid taxes and other claims by Mali’s military junta. They were released after the company agreed to pay US$160M in compensation for adjustments to taxes and royalties in line with the 2023 Mining Code.

Resolute operates the Syama underground gold mine (2.4Mtpa), located 300km southeast of Bamako, Maili’s capital. The mine hosts 1.86Moz grading 2.5g/t gold on a 100% basis.

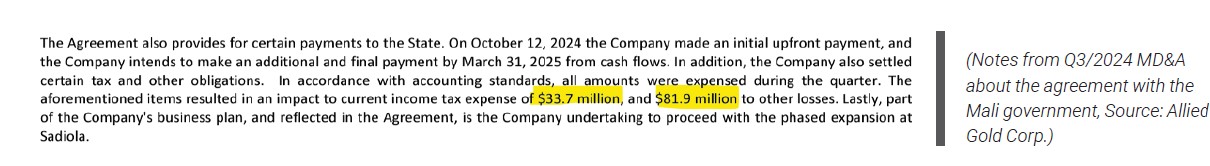

Allied Gold (TSE: AAUC), one of the weakest performers among the peer group, negotiated a 10-year exploitation permit for the Sadiola and Korali-Sud gold mine in Mali in early September 2024. The deal includes a one-time payment of about US$115M to resolve any outstanding disputes along with a relaxation of the royalties under the 2023 Mining Code.

Besides Mali pushing for greater rents under its revised mining code, Niger’s military junta has recently taken control of Orano, a French nuclear company, and its Somair uranium operation.

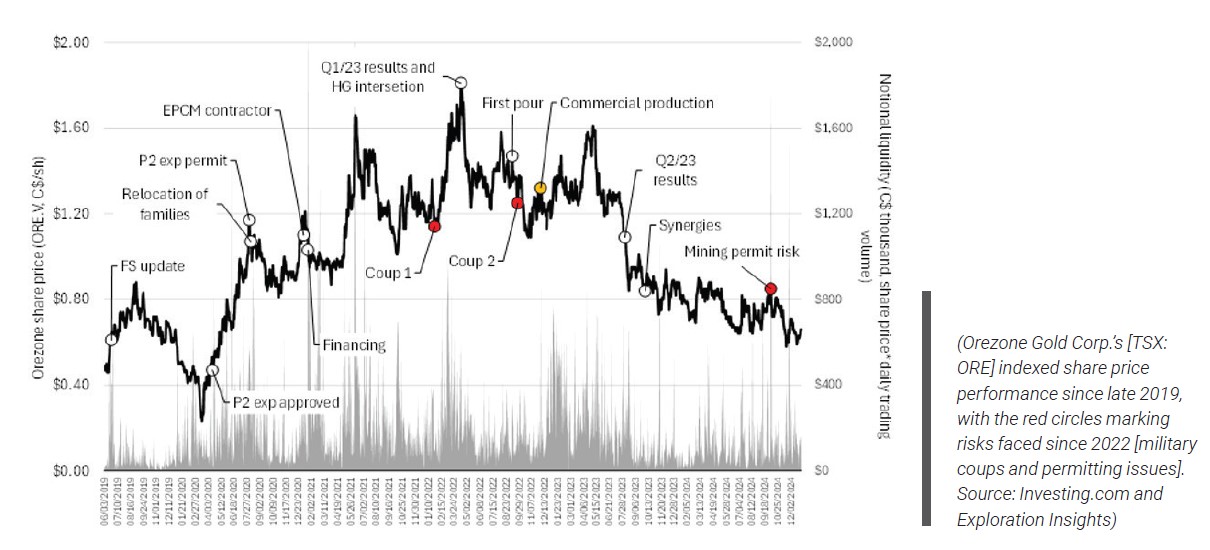

Finally, Orezone Gold Corp. (TSX: ORE) completed a feasibility study on its Bomboré gold mine in Burkina Faso in mid-2019 and declared commercial production at the end of 2022. Its poor share price performance in the past two years suggests that the risk of operating in a politically unstable country have offset its successful transition to a single-asset producer.

So why is West Africa getting riskier?

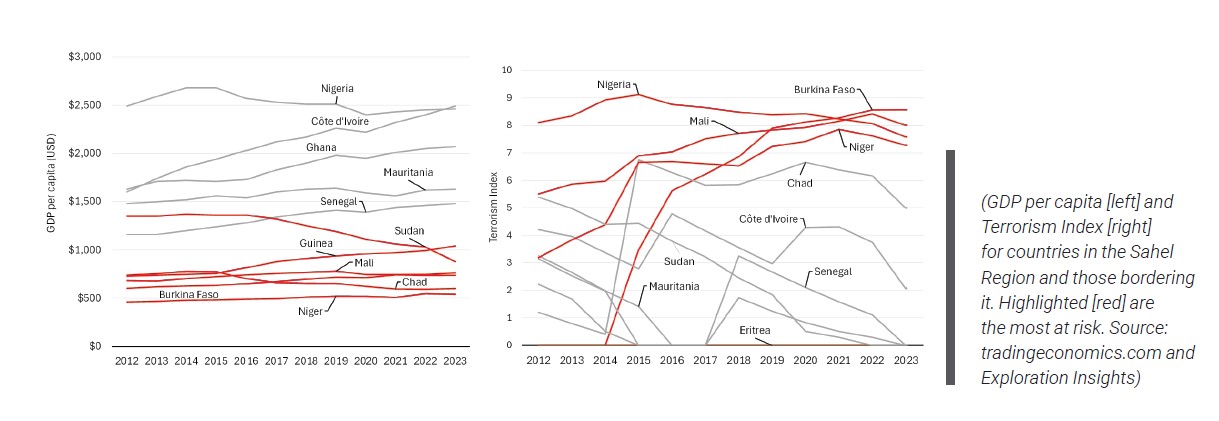

Several major gold-producing nations are located within or bordering northern Africa’s Sahel Region, a 5,400km east-west land belt sandwiched between the Sahara Desert to the north and sub-tropical Africa to the south.

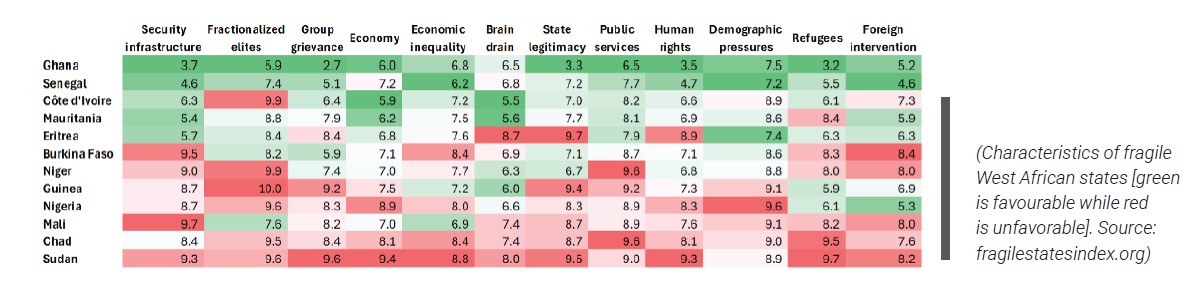

This is an area with a long history of instability, several countries including Chad, Burkina Faso, Mali, Mauritania, and Niger have experienced a combined 25 successful coups d’état between 1960 and 2022, according to the Global Conflict Tracker. Some analysts suggest that the seeds of the recent turmoil may have been sown during the dismantling of the Libyan state in 2011.

The ensuing terrorism driven by Islamic extremists has continued to threaten the region. Task forces created by local civilian and European governments, specifically France — as most countries in the Sahel were former colonies — have unsuccessfully disarmed these groups giving rise to military juntas that have deferred the return to civilian rule indefinitely. The military leaders have abandoned regional alliances (e.g., ECOWAS) to form their own, while Russian mercenaries such as the Wagner Group have filled the gap left by France’s exit.

Analysts highlight that textremism’s expansion in the Sahel Region and beyond is due to various reasons, including persistently fragile governance, group grievances, weak state legitimacy, demographic pressures, economic instability, human rights abuses, and foreign intervention, with Sudan, Chad, Mali, Guinea, Niger, and Burkina Faso being the most problematic.

These struggling nations seek funds to support their military objectives from the largest contributors to their GDP, such as the multinational mining companies, specifically at a time of rising commodity prices.

Regional impacts of creeping nationalism

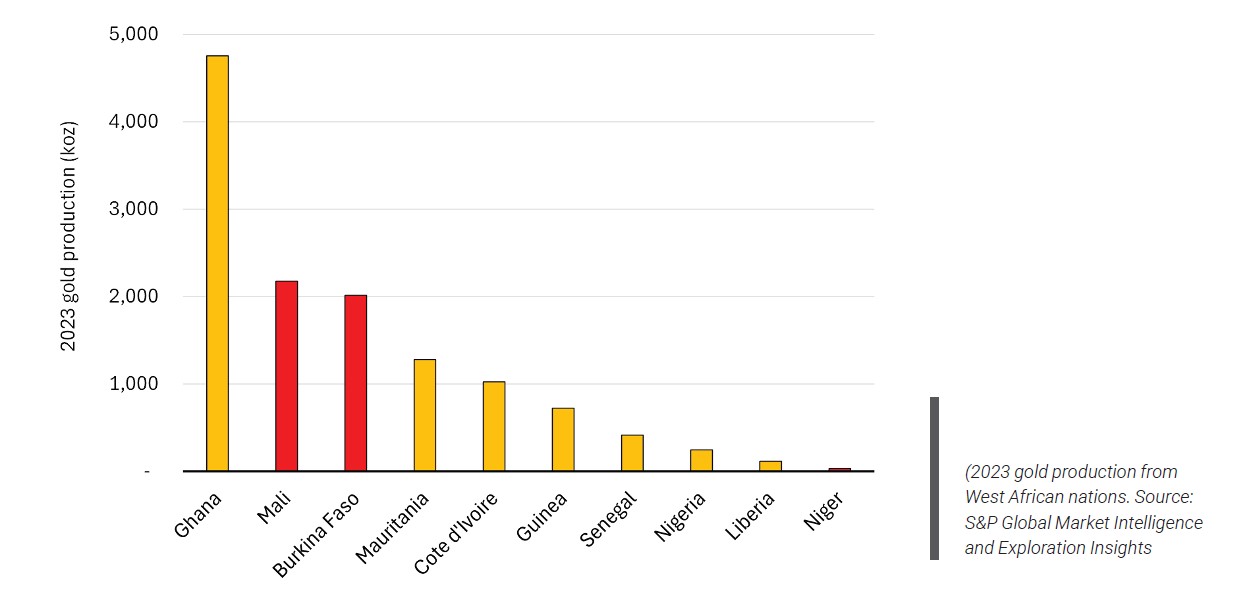

The attraction of operating in this part of the world for mining companies is its unquestionable mineral endowment — the region produced about 13Moz of gold in 2023, or 13% of global gold production — coupled with relatively fast paths to production and straightforward permitting processes. For example, Endeavour Mining (TSX: EDV) reported the feasibility study for its Houndé gold project in Burkina Faso in 2013 and broke ground only three years later.

Despite the challenges of operating in the most unstable nations, like Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger, for western multinational companies, the impact on gold production might be minimal if competent operators from Russia or China take control.

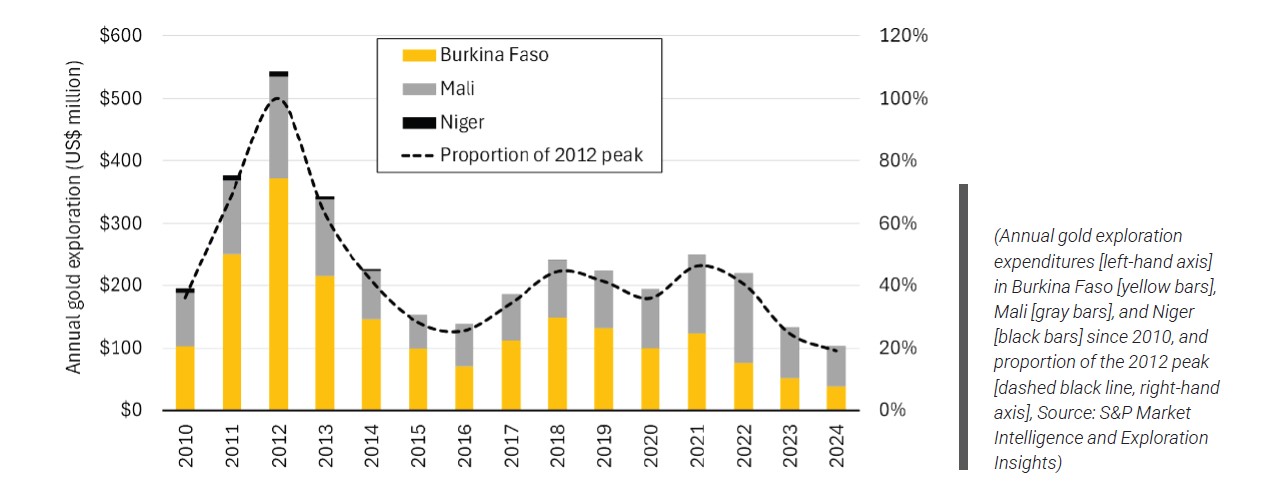

Regardless, future investments from Western sources are expected to decline. Exploration expenditures in Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger peaked in 2012 at US$540M, but are estimated to have declined by 20% in 2024 (US$100M), as the dwindling supply of funds to support exploration flowed to where it was more welcome.

On a positive note, the unfavourable geopolitical situation in these countries has generated growing interest in their neighbors.

In 2024, Montage Gold (TSXV: MAU), which operates the Koné project in Côte d’Ivoire, raised C$180M in equity with long-term holders Lundin Group and Zijin Mining (OTC: ZIJMY), and an additional US$825M in gold streams and loans from Wheaton Precious Metals (TSX: WPM) and Zijin Mining, to build the mine, which hosts 4Moz of gold grading 0.72g/t in reserves.

In addition, following its divestment of the Nampala mine in Mali, Robex Resources (TSXV: RBX) raised C$125M in equity and is organizing a US$130M debt facility to fund the development of a 3Mtpa operation at the Kiniero gold project (85% RBX) in Guinea, which hosts ~1Moz of reserves grading 1.09g/t.

Conclusions & summary

West Africa’s strength lies in its gold endowment and favourable timelines for permitting and development compared to other regions where the social license to operate is harder to procure.

The combination of poor infrastructure (power, roads, etc.), high security costs, and creeping nationalism has forced several companies to rethink their strategy and deploy capital elsewhere.

Despite geopolitical risks, mining operations owned by local governments might be sold to Russian, Chinese, or capable local operators, resulting in a minimal impact on regional gold production.

Western companies willing to operate in these jurisdictions will need to diversify their asset portfolio to mitigate risk and lower their cost of capital.