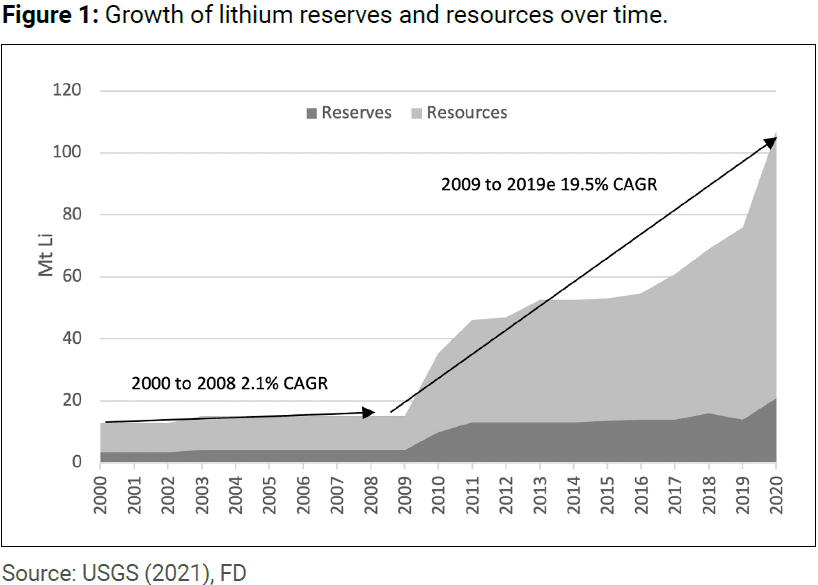

Primary lithium demand began to grow from 2007 onwards as the demand and manufacture of lithium-ion batteries required an immediate supply reaction. Exploration success quickly followed, using existing geological models, targeting salars and pegmatite operations. Displaying a classic supply response, from 2009/10 onwards, additional lithium reserves and resources were being delineated (displayed cumulatively – see Figure 1).

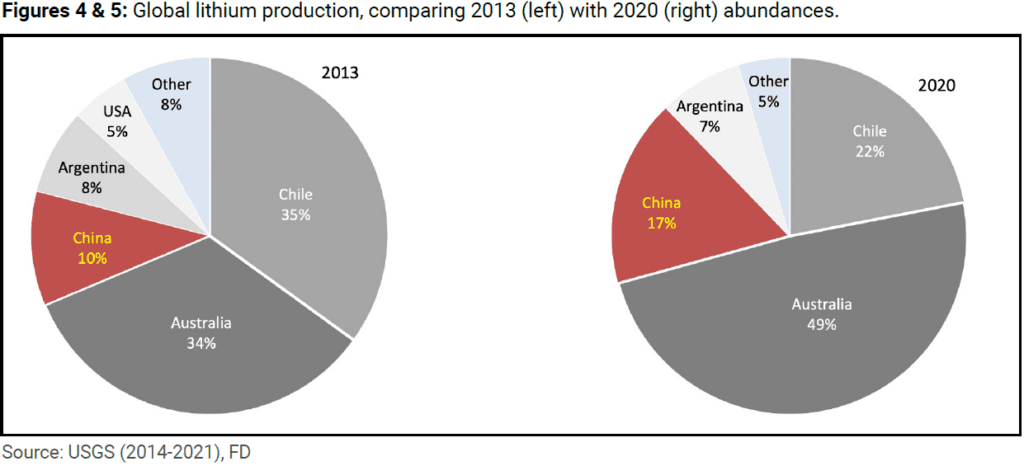

Taking a snap shot in time, production in 2013 was dominated by Chile and Australia (see Figure 4), however, substantial nameplate capacity was added from 2015 onwards, in particular a threefold increase in output from Greenbushes has meant that global production is increasingly dominated by Australia (see Figure 5). This position is expected to be challenged in the near future by new and existing facility expansions, primarily in South America. These include SQM expansion at its Atacama salt flat operations, Australia’s Wesfarmers (ASX: WES) FID on the Mount Holland project, Albemarle (NYSE: ALB), readjusting plans to add about 125kt of processing capacity, while IGO Ltd (ASX: IGO) sold its 30% stake in Tropicana, to fund its lithium expansion plans.

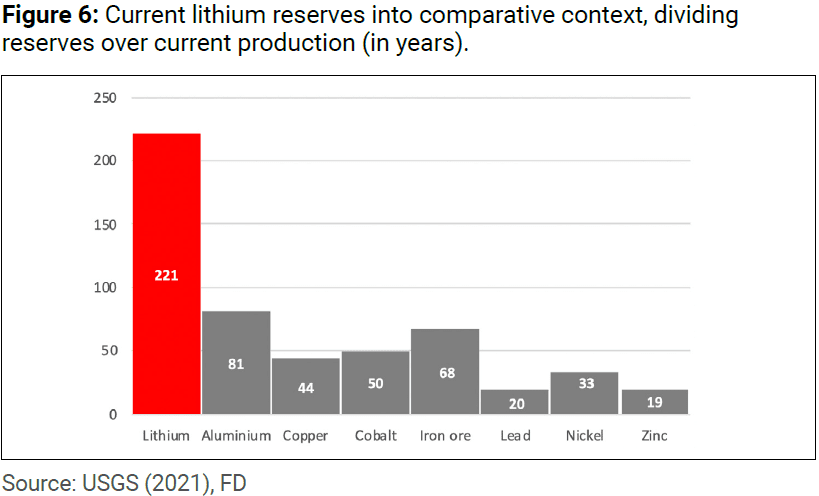

Reserve numbers equate to >220 years’ supply at current production rates (see Figure 6). If we include resources, we have an additional ~1,150 years of supply at current demand.2 However, these kinds of numbers show nothing regarding supply and demand dynamics, or the economics behind extraction. For example, at the height of the last iron ore boom, BHP and Rio were spending, on average, US$200m per Mtpa additional capacity, despite hundreds of years of proven resources. Despite record prices, only a single company joined the ranks of the seaborne oligopoly (i.e. Fortescue), and much of that can be attributed to a unique individual, an unconventional and (at the time) unproven mining technique.

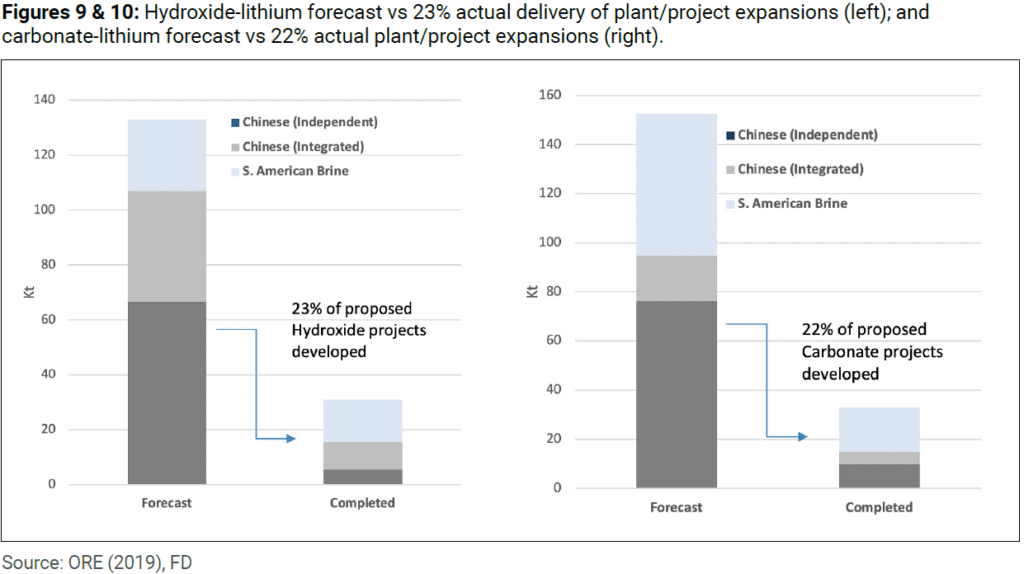

The key takeaway in understanding future lithium supply is that the quantum of global resources is meaningless. Despite a 200% increase in global lithium output as a result of various mergers, particularly led by the Chinese, the market has continued to consolidate the existing oligopolistic market structure (see Figures 9 & 10). Lithium supply has to be viewed within certain economic parameters, that the theoretical wave of supply about to inundate demand, will never eventuate; as explained in the following section titled, the “Bow-wave Effect”. Not unlike the seaborne iron ore market, the oligopoly market structure allows producers to cut or expand output quickly according to perceived demand or supply, in turn providing a disincentive for other potential participants (i.e. Greenfields explorers) to secure developmental funding.

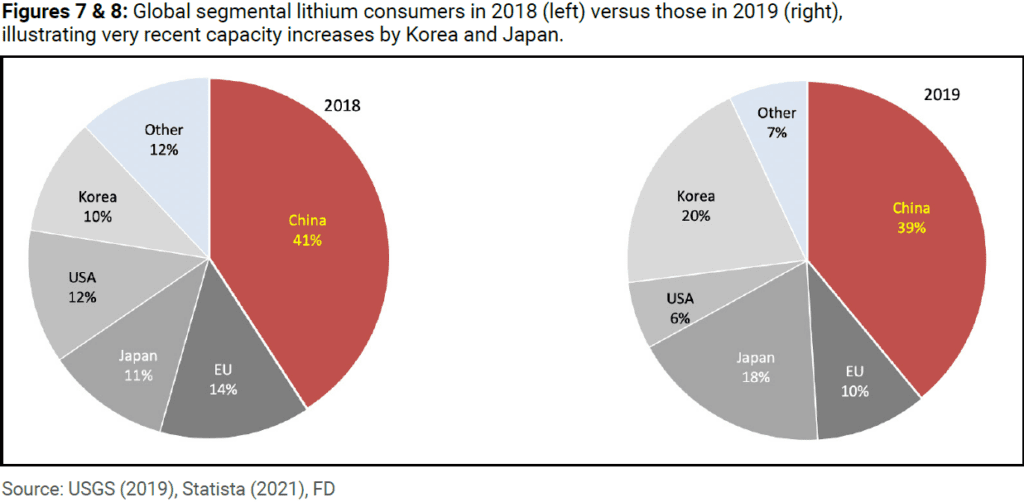

Recent production capacity increases have been driven more recently by Japan and Korea, propelled by EV Li-ion battery demand, accounting for >71% of global sales. Historically, China’s dominance in the lithium market has, in large part, been the result of it being the world’s largest EV market in 2020 making up >56% of vehicles sold globally, and >95% of the commercial vehicles in operation; collectively, substantially larger than the rest of the world combined.

‘Bow-wave Effect’? Production always less than forecast

The phrase “Bow-wave Effect” describes the pattern behind the addition of productive capacity for any commodity (with the exception of gold), which bears little or no relation to the underlying quantity in resource base. As the analogy implies, the boat that follows behind never quite catches the “bow-wave”. Not unlike many other commodities, there is always the appearance of an enormous “wave” of potential lithium supply about to engulf the market. However, what inevitably comes to fruition is merely a fraction of stated/planned capacity and, in lithium’s case, the vast majority of additional capacity/new projects has been brought online by existing, not new, producers (see Figures 9 & 10).

This “bow-wave” analogy has several important market implications, namely:

- Only existing (or very few new) lithium entrants will add to primary supply

- Until recently, there was excess capacity among existing brine producers (rumours that some salar operations were operating at 60% nameplate capacity) will dissuade the debt markets from providing developmental funding to new entrants. This will suit existing market participants, who will continue to actively manage supply to align with perceived demand growth, for at least the next several decades

- The large existing resource base (see Figure 8) and surplus capacity from recent developments, coupled with the industry’s ability to increase production rapidly, will continue to deter Greenfields investments; and is the primary reason why the lithium market has retained its oligopolistic structure

The above oligopoly market structure is not dissimilar to what we observe in the iron ore sector, that despite seaborne iron ore tonnages increasing >275% over the past two decades, with the sole exception of Fortescue Metals, virtually all of the additional global seaborne capacity came from three existing iron ore-based Mining Houses: the Australian BHP and Rio, and Brazil’s Vale.

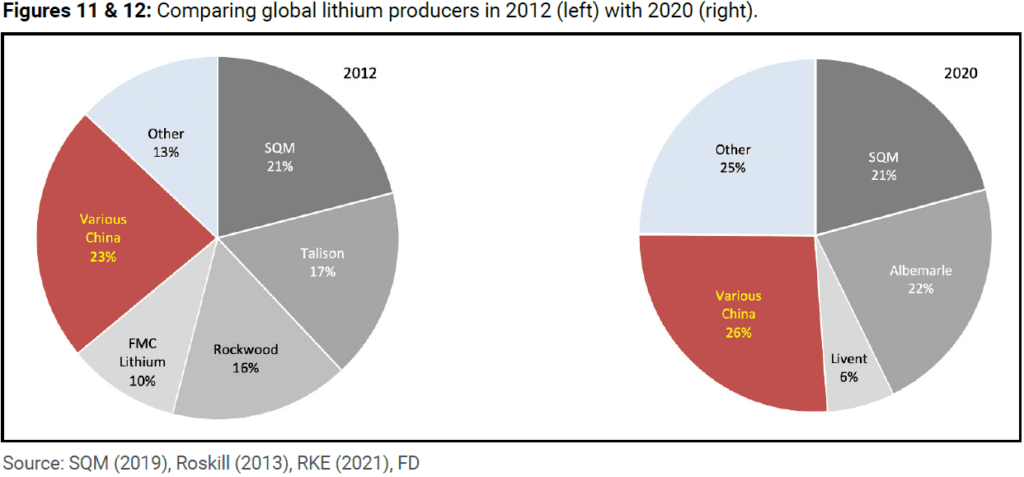

In 2012, global lithium production was dominated by four producers (and China). In the intervening eight years, despite global production increasing 100%, primary supply is arguably even more concentrated (see Figures 11 & 12). We believe that this market consolidation will continue to occur despite the fact that we believe that lithium demand will double over the next decade. As evidenced with Australia’s Orocobre buying Galaxy for $1.4B; creating the world’s fifth largest lithium miner, combining hard rock, brine, and chemical assets across Australia, Argentina, Canada, and Japan.

Superficially, there are very few corporate or operational synergies to be gained, other than strengthening its balance sheet (~$487M cash), improving access to finance and streamlining product marketing. Critically, it will allow plans for the merged entity to more easily finance its increased production to >130kt LCE (lithium carbonate equivalent), up from ~40kt currently. Particularly interesting is Rio Tinto’s entrance into the sector, following a breakthrough production process at its Boron mine, recovering lithium from waste piles accumulated over the past 90 years, with an FID pending ($50M capex for 5kt pa lithium carbonate). Critically, Rio has another borate project in Serbia that may also begin to produce lithium as a co-product. If these projects are successful, expect Rio to make a major acquisition.