We are moving into a new order for critical minerals, with enormous demand being forecast for the coming decades. This demand is inevitable for building a better, greener world, a new digital economy, modern industrial systems, and a reduction in the impact of climate change. It’s a transformative moment with the advent of energy transition, possibly the most transformative since the industrial revolution. We will not have a sustainable future without mining these so called “critical minerals”.

But what makes some minerals critical and others not so much?

What makes a mineral critical or not, depends on which country we are posing the question to. However, generally speaking, there are several overlaps for what is considered to be “critical” across many nations. Some common characteristics that define critical minerals is their (i) lack of substitutability, (ii) inconsistent distribution of reserves or processing leading to concentration, (iii) their usages in industries driving energy transition, (iv) strategic importance such as in defense, as well as (v) heightened geopolitical risks. These minerals are usually dispersed across the globe and countries are racing to strategize around securing their value chains for meeting their energy transition targets.

Critical minerals also have very dynamic and diverse upstream, mid-stream, and downstream interests, making the ecosystem for operations extremely complex. Upstream extraction is often undertaken in developing and sometimes challenging jurisdictions, while the processing is mostly happening in mainland China. Unlike oil and gas, where economies of scale have developed over several decades, critical mineral usages, often in small quantities, usually don’t warrant a rapid pace of expansion. Supply chain diversification has, therefore, become the most critical issue, when it comes to these critical minerals. At the same time, resource nationalism and environmental challenges will pose risks leading to nearshoring and regionalization initiatives.

For the energy transition, copper will remain a core material for transmission lines, wind turbines, solar panels, and energy storage systems, making it very important for most countries. Copper has remained a key building block for our modern world, be it in lighting or communication. Looking ahead, as per S&P Global’s “Future of Copper” study conducted in 2022, global refined copper demand is projected to “almost double from just over 25 metric tons in 2021 to nearly 49M metric tons in 2035, little more than a decade away”. This is mostly on account of expansion of the solar and wind energy infrastructure, which are typically 10-20 times more copper intensive.

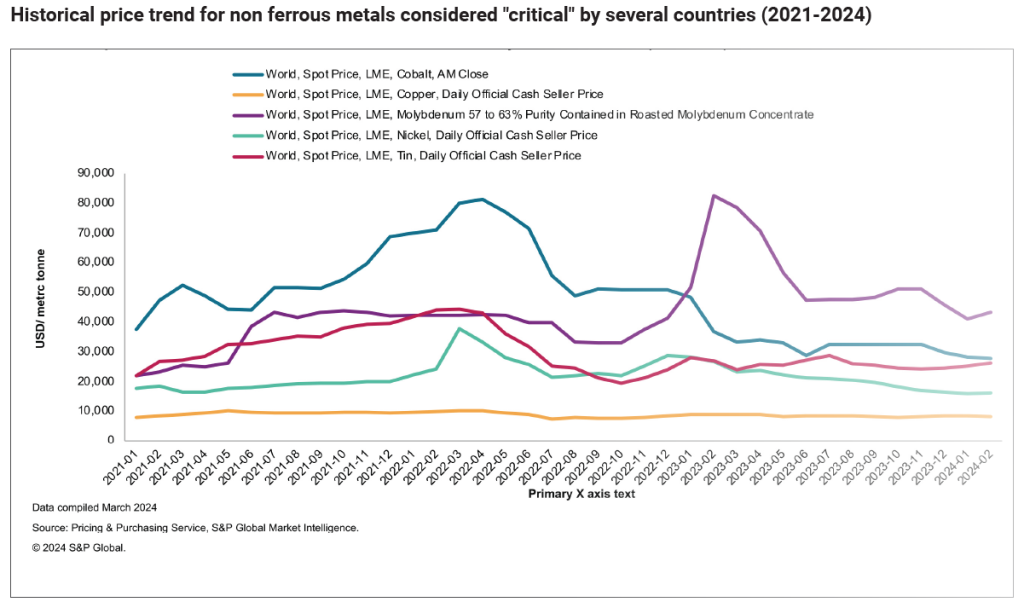

The value chain for critical minerals isn’t about extraction alone, but understanding how the minerals are processed, and where they are processed. The nature of global resource competition is changing quite rapidly, but there are a lot of embedded questions. Prices of these critical minerals are, as a result, always throwing surprises or exhibiting volatility, such as in the case of lithium recently. The subject matter itself comes at an intersection of environmental, social, economic, geopolitical, trade, and partnership challenges and opportunities, making these critical minerals vulnerable to risks of various kinds.

Asia also remains at the centre of conversations around these important minerals. Australia accounts for 46.6% of 2023 global lithium output, followed by Chile (23.8%) and mainland China (17.9%). Mainland China possesses over half of global lithium processing capacity. Around 45% of 2023 global nickel output was sourced from Indonesia and the Philippines. Approximately 90% of global lithium and rare earth metals and 70% of copper, nickel, and graphite are also processed in APAC countries.

Given this essential need for mining these critical minerals, it’s also important to understand if the mining industry is geared to meet this demand tsunami. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), in the next two decades, demand for nickel and cobalt will increase by 60-70%, copper and rare earths will increase by over 40%, and lithium by about 90%. Therefore, it’s clear that miners have a big ask and an enormous responsibility, especially with sustainability frameworks adding another layer to pressure to help transform the world to a modern, yet greener planet.

Unlike in the past, mining is not just about unearthing anymore. There are several challenges such as locating virgin ore bodies and need for heavy investments for active exploration budgets, extraction, and beneficiation. Funding mining and downstream processing via equity is no longer viable in several countries on account of huge upfront investment required, and governments often must come in to offer investments via the debt route. Additionally, the lead times are often getting longer given that it takes 10-15 years to develop a virgin mine due to cumbersome licencing processes in certain countries as well as greater scrutiny on sustainability parameters. Mining in mineral rich regions impacted by conflict such as Ukraine and throughout Middle East is ridden with hurdles, so essentially those ore bodies are out of the purview. Similarly, regions with higher rainfall also cannot be considered actively since it potentially creates issues with the tailing dams or environmental liabilities.

With the race for securing these critical minerals intensifying in the coming decades, countries that succeed will be the ones that develop a “whole chain” mindset

Looking forward, miners will need to mine fast yet in a sustainable way. Miners are likely to be increasingly conscious of where the energy to mine is coming from, ensuring sustainable practices, building relationships with host communities and including more women in the workforce. Despite all these challenges, mining industry is also heavily re-inventing itself, what with technological upgradation, ESG, and DEI commitments happening concomitantly with extension of the life of mine. Countries, on the other hand, will have to support miners, with the country-specific critical mineral strategies in place. With the race for securing these critical minerals intensifying in the coming decades, countries that succeed will be the ones that develop a “whole chain” mindset. However, managing the whole chain related to exploration, mining, beneficiation, separation, metallurgical applications, and recovery could only be possible by establishing exclusive alliances and trade partnerships.