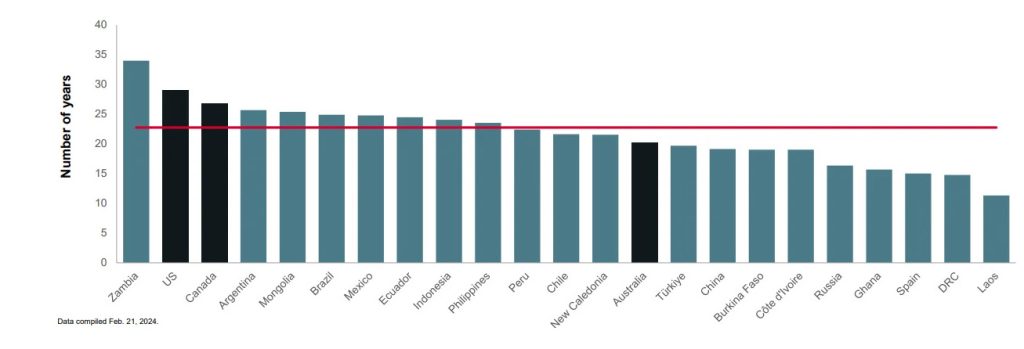

The mining sector is being challenged by increasing jurisdictional risk, as highlighted by a recent S&P Global Market Intelligence report. The timeline from discovery to commercial production for ore deposits is growing and now averages 20-25 years (Fig. 1), with assets in the so-called “low-risk jurisdiction” of the US and Canada facing even lengthier periods of 25-30 years.

Intelligence

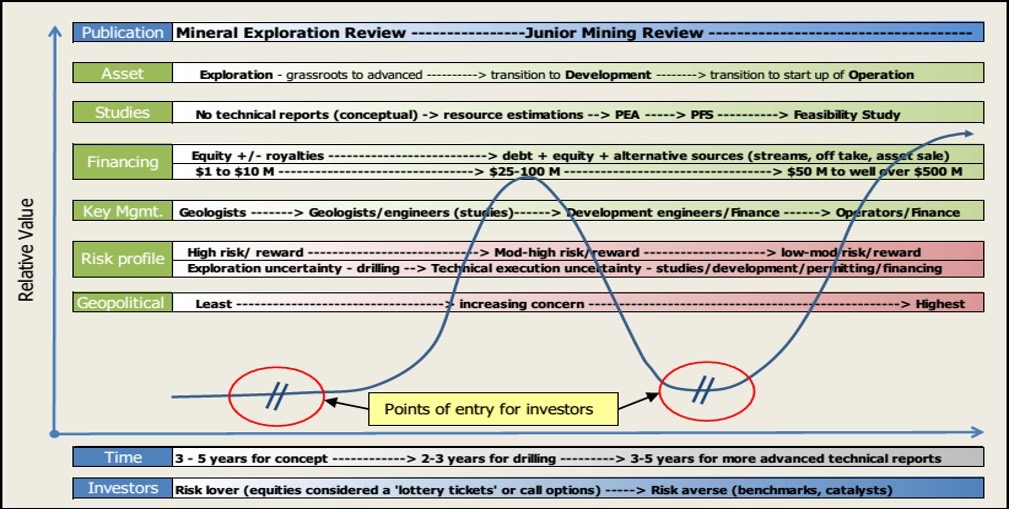

Engineering advances have shortened the construction timeline but not the time required for establishing a social licence to operate and obtain development permits. Prolonged timelines demand significant capital, often leading to a loss of shareholder support during the so-called “orphan period”, where projects remain undeveloped and risk being abandoned (Fig. 2).

development phase, also known as the “orphan period”. Source: Canaccord Genuity and Exploration Insights

Private land favoured in the US

In the US, the fluctuating regulatory landscape further complicates these timelines, with projects like Resolution Copper, Rosemont in Arizona, and Pebble in Alaska facing significant setbacks due to oscillations between different administrations. This political ping-pong heightens the risks and complicates long-term investments in substantial mineral projects, some of which may be required to supply future carbon-neutral technologies.

In the US, the impacts of alternating regulatory landscapes are evident with projects in Alaska, Arizona, and Minnesota facing significant setbacks:

- The Resolution underground copper project in Arizona was discovered in 1995 and is operated by Rio Tinto Plc. (LSE: RIO | NYSE: RIO). The project saw its draft Record of Decision (ROD) rescinded in March 2021, but a 2014 land swap deal appears to be finally moving forward

- The Arctic open-pit copper mine in Alaska, a joint venture (JV) between Trilogy Metals (NYSE: TMQ) and South32 (ASX: S32), had the 211-mile-long Ambler Access Road, being advanced by the Alaska Industrial Development and Export Authority (AIDEA), rejected by the US Department of Interior. If there is no road, there is no mine

- The Rosemont copper project in Arizona was modified by HudBay Minerals (NYSE: HBM) into the Copper World project, now predominantly on private land to avoid federal permitting

- Antofagasta Minerals’ (LSE: ANTO) Twin Metals nickel project in Minnesota was blocked due to concerns about local waterways

- The large Pebble copper mine in Alaska, operated by Northern Dynasty Minerals (NYSE: NAK), has been denied water-related permits by the US Army Corps of Engineers

To mitigate some of these challenges, companies are increasingly looking towards projects on private lands, which can offer a smoother permitting path as they require only state permitting if the project does not have any waters of the US (WOTUS).

For example, Arizona Sonoran Copper Company’s (OTC: ASCUF) [I own shares of ASCU] Cactus-Parks/Salyer open pit/underground copper project benefits from its location on private land, water access, and support from the business-friendly community of Mesa.

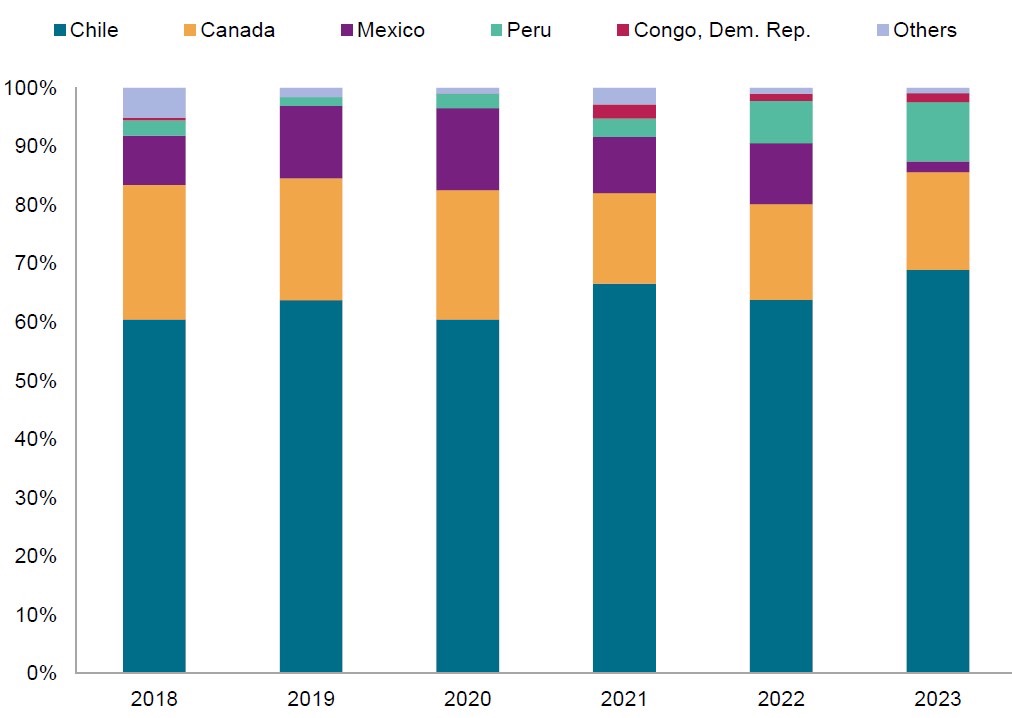

Meanwhile, the US reliance on imported copper cathodes, mainly from Chile (~65%), followed by Canada and Peru, underscores the strategic vulnerability associated with long project lead times (Fig. 3). Mexico has fallen as a source of cathodes, offset by Peru and Chile. Interestingly, China takes up a higher portion of Chile’s copper cathode exports than the US (40 vs 20%).

The local (US) production of copper cathodes, such as that proposed by ASCU’s solvent-extraction electrowinning plant at the Cactus project, as opposed to a concentrate that would have to be shipped overseas, illustrated the strategic benefit of the project.

Mexico getting riskier

In Mexico, the mining landscape is becoming increasingly complex under the anti-mining Morena administration of Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO), which introduced reforms in 2023 that could restrict mining activities significantly.

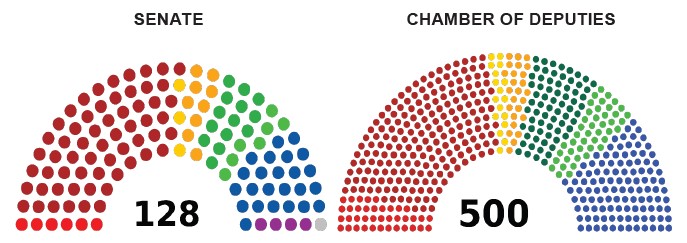

Following the June general elections, AMLO will continue in his office until October; however, his hand-picked successor, climate scientist Claudia Sheinbaum, will likely follow his agenda. Apart from the presidency, Morena currently controls 23 of the 32 state governments (Fig. 4). This evolving policy environment necessitates a careful reassessment of investment strategies in the region.

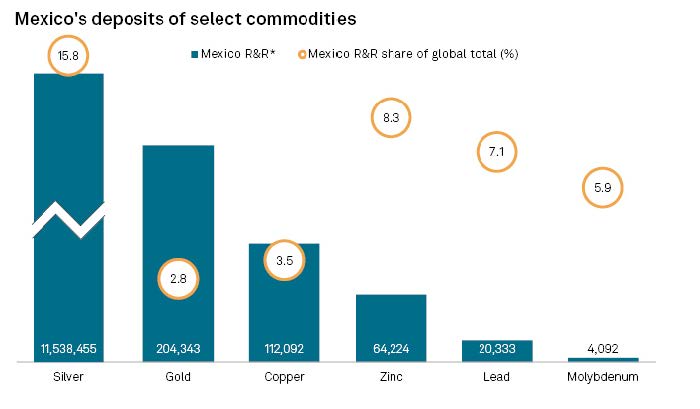

Despite being a significant producer of silver, gold, copper, lead, zinc, and molybdenum (Fig. 5), the restrictions on new exploration and water concessions, along with a proposed ban on open-pit mining, are seismically problematic for the domestic mining industry.

Proposed changes to the constitution, which include a ban on open pit mining, require a Congress or Chamber of Deputies supermajority (2/3rd), which is currently being contested in the Supreme Court.

The following commentary comes from a recent meeting with Mexican lawyer Carolina Franco Bell of Franco, Ríos Muñoz y Asociados, S.C., based out of Mexico City.

There are 500 seats in the Chamber, but only 300 of which are directly related to votes while the remaining 200 are assigned proportionally to the votes each party receives to a maximum of 8% (Fig. 6). For example, if a party obtains 40% of the votes, it can have a maximum of 48% of the deputies.

Currently, Morena and its allied parties (PT and Verde) have more deputies than the percentage of votes obtained in the elections (74% vs 54.7%). While the “overrepresentation” is legal as laid out in the constitution, the opposition argues it is excessive (19% vs 8%) as the limit should be applied to the whole coalition (Morena, PT, and Verde) rather than to each party.

Importantly, if the 8% limit is applied to the coalition, Morena and its allies would lose the supermajority (62.7% < 67%). The Electoral Tribunal is analyzing the case and must issue a resolution before the Chamber of Deputies takes office on 1 September 2024.

The increasing risk of operating in Mexico became clear in two recent M&A transactions involving the sale of producing and developing gold assets for little cash upfront. Alamos Gold (NYSE: AGI) acquired Argonaut Gold, generating a spin-out of the latter’s Mexican gold assets (El Castillo Complex, La Colorada, Cerro del Gallo, and San Antonio). Subsequently, the spinco – Florida Canyon Gold – sold the Mexican portfolio to Heliostar Metals (CVE: HSTR) for US$5M.

Given the current situation, I have adopted a wait-and-see attitude, as I think the main risk is constrained to exploration and development companies, rather than producers.

Harsher rules in British Columbia for exploration

During a recent site visit to the Kitsault Valley Project operated by Dolly Varden Silver Corp. (OTC: DOLLF) in northern British Columbia (BC) (Fig. 7), I learned of a C$195M joint investment by the Canadian and BC governments “to improve community access and safety and create mining jobs across the province and support critical minerals development in the region.”

lounge [bottom left] and Dolly Varden camp [bottom right]. Source: Exploration Insights

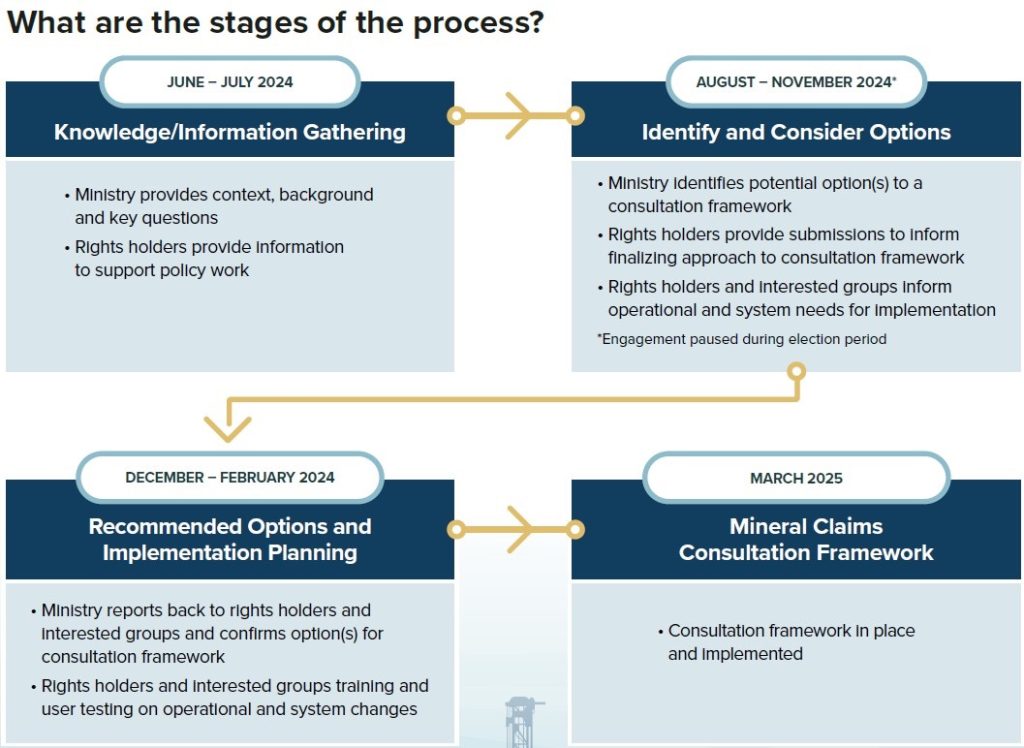

At the same time the left-leaning BC government is trying to support mineral projects in remote regions of the province, the Provincial Supreme Court (BCSC) is making things more complicated. The court has mandated that the BC government overhaul the existing Mineral Tenure Act (MTA) by April 2025, which may hinder future exploration efforts.

The government has recently published a process flowchart to achieve this goal by March (Fig. 8). The potential outcome is to enforce consultations with First Nations groups before staking exploration ground in their territories, a practice that until now was conducted mostly online.

Consultation with First Nations groups by junior explorers is standard practice after the ground is acquired but not before. The risk of not obtaining the ground through staking that your geological expertise identified may lead explorers to take their limited resources to greener pastures.

Potential solution derived from improbable source

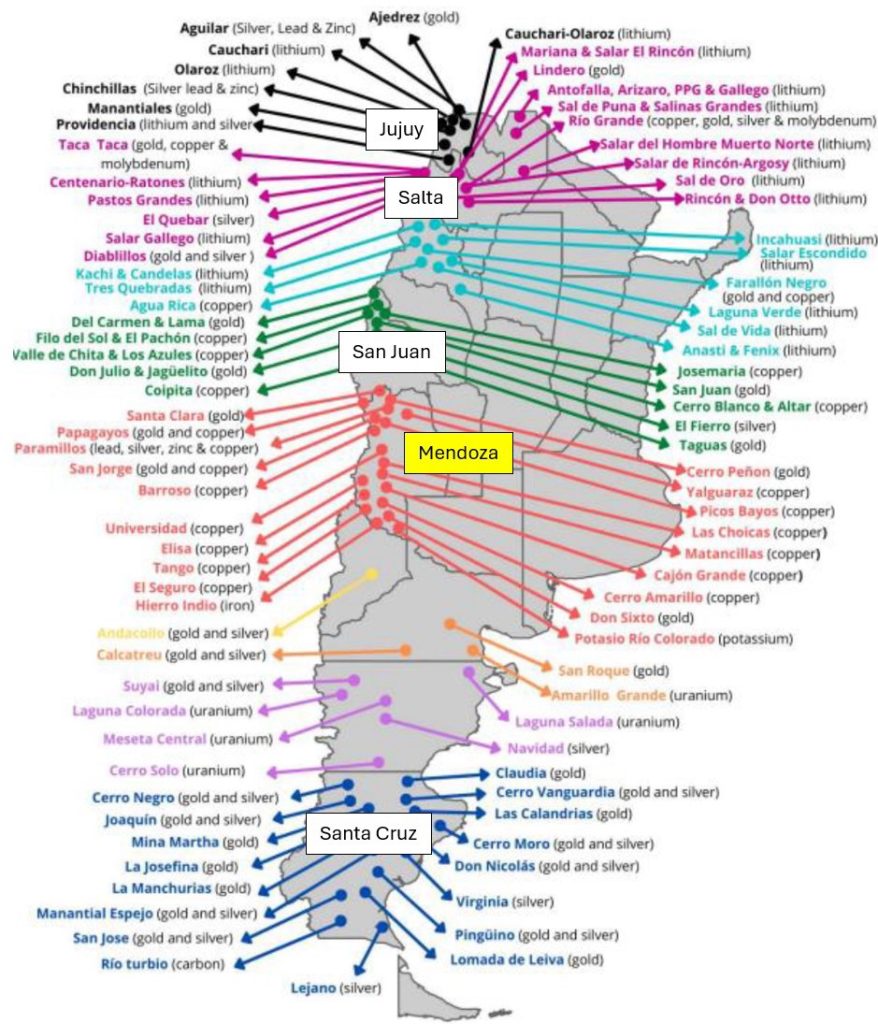

In the first half of 2024, I was invited twice to the province of Mendoza in Argentina, a highly prospective region (Fig. 9), that had not been favourable to mining during my time working in the country in the 1990s, to advise them with revamping the local mining industry.

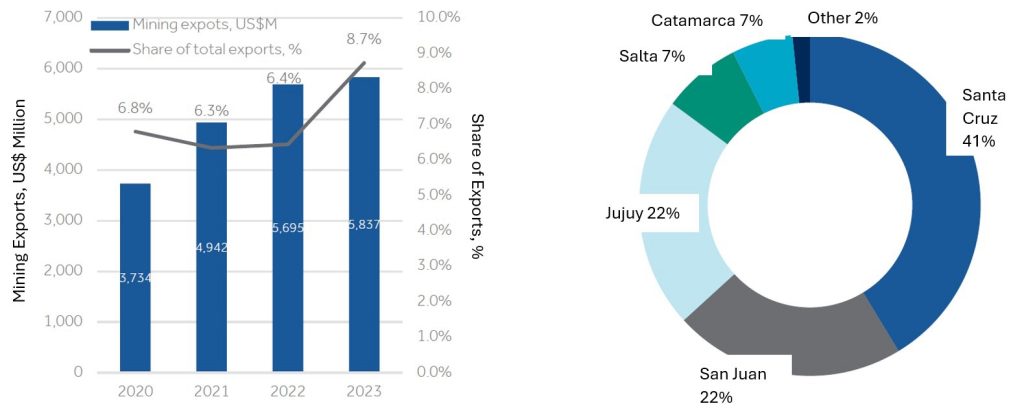

Local resistance had led to a 2007 ban on the use of key chemical substances (cyanide, sulphuric acid) for the extraction of metals, isolating the province from Argentina’s lucrative mining industry. In 2023, mining represented 8.7% of Argentina’s exports or US$5.8B mostly from just five provinces, with Mendoza notably absent (Fig. 10).

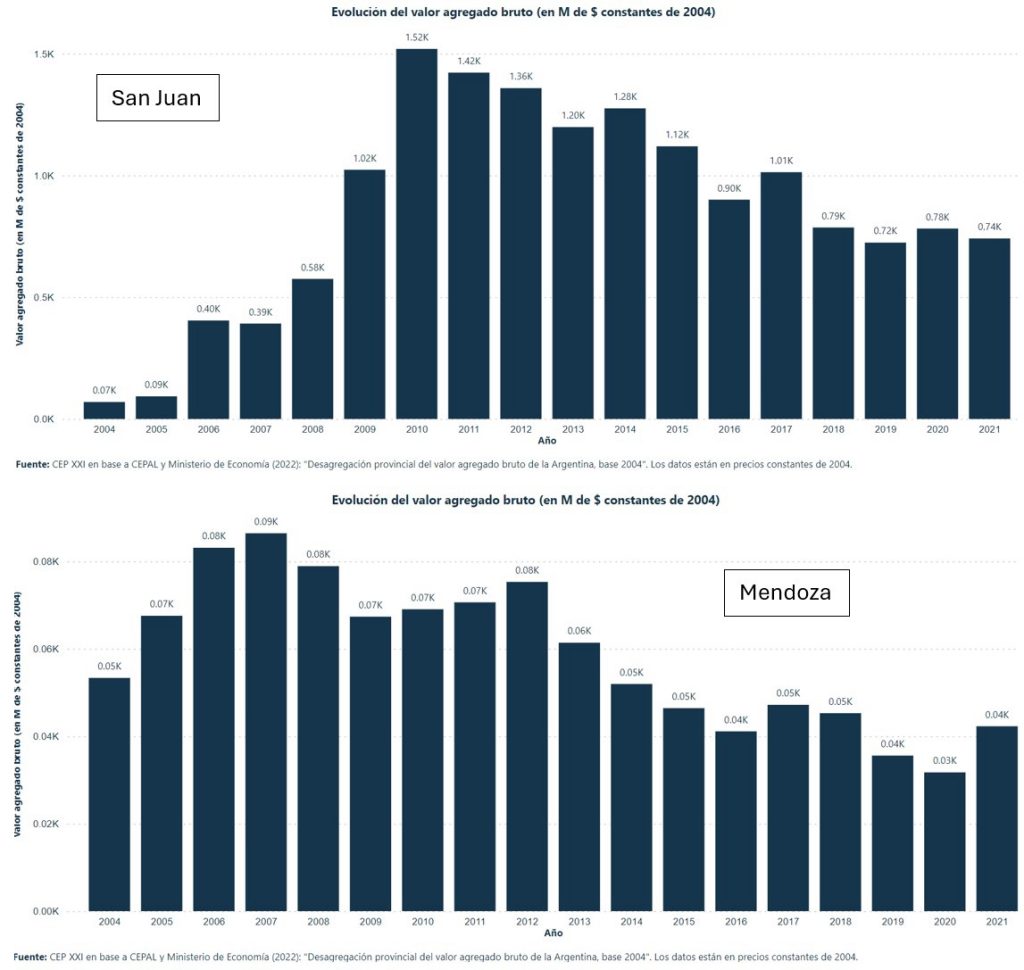

Mendoza’s steady population growth — up 45% over the past three decades — and lack of industrial growth has kept its GDP per capita at 35-40% below the national average. Recognizing the urgent need for economic diversification, local government, and industry leaders are reevaluating their stance on natural resource exploitation as a source of GDP growth, following the lead of its neighbouring province, San Juan (Fig. 11).

Mendoza. Source: CEPAL and Ministry of Economy of Argentina)

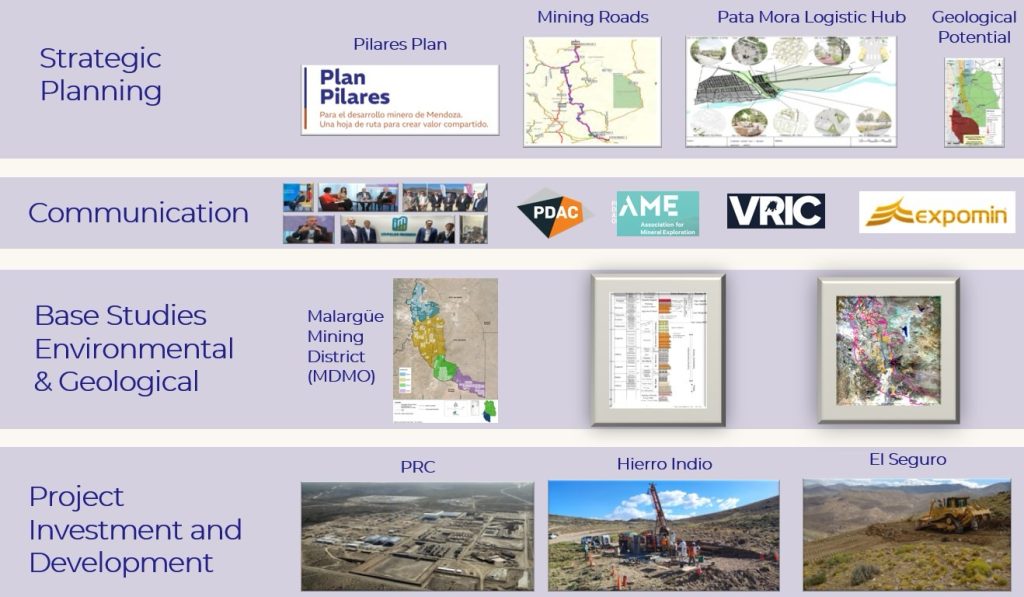

My discussions with Mendoza’s business leaders (Fig. 12) were sponsored by Impulsa, an initiative aimed at fostering a sustainable mining sector in the southern part of the province, specifically the Malargüe Occidental Mining District, that could potentially be expanded to other regions.

Mendoza. Source: Exploration Insights

Impulsa’s innovative approach involves identifying favourable projects for exploration and potential development while, critically, conducting a thorough pre-consultation and baseline environmental studies before any engagement with interested mining or exploration companies (Fig. 13).

The strategy aims to mitigate potential social licence-to-operate (SLTO) risks upfront, allowing companies to concentrate on discovery risks at the end of a drill bit. This model, if successful, could not only transform Mendoza’s economic landscape but also serve as a blueprint for other regions facing similar challenges.

Conclusions

In numerous so-called low-risk mining jurisdictions such as the US and Canada, the journey from mineral discovery to production is increasingly protracted, often stretching across a few decades.

While I advocate for robust regulatory oversight — as exemplified by projects like the Eagle Mine in the Yukon which needed greater scrutiny — the revocation of a previously granted construction permit disrupts not just the project, but also undermines investor confidence. Having to look for alternative solutions, such as opting for projects on private lands over public ones, to sidestep these hurdles, should not become the norm for the industry.

An innovative approach comes from the province of Mendoza, Argentina. Historically resistant to mining, the province is shifting its strategy to attract responsible investors. The local government and industrialists are developing a process whereby they would engage with local stakeholders early, ensuring environmental and social governance standards are met before any mining activities.

I think this model could be readily adopted globally by other governments aiming to enhance their GDP through mineral exploitation, fostering a more sustainable and community-friendly mining industry.