The Inflation Reduction Act has seen an eventful first year in action, catalyzing US$270B in investments and at least 83 new or expanded manufacturing facilities as a result, according to the American Clean Power Association.

The Inflation Reduction Act, or IRA, has attracted heavy investment into US battery supply chains that largely did not exist prior. Passed on 16 August 2022, it was enacted by the US Congress and President Joe Biden to stimulate funding and support efforts towards US goals for net-zero emissions by 2050.

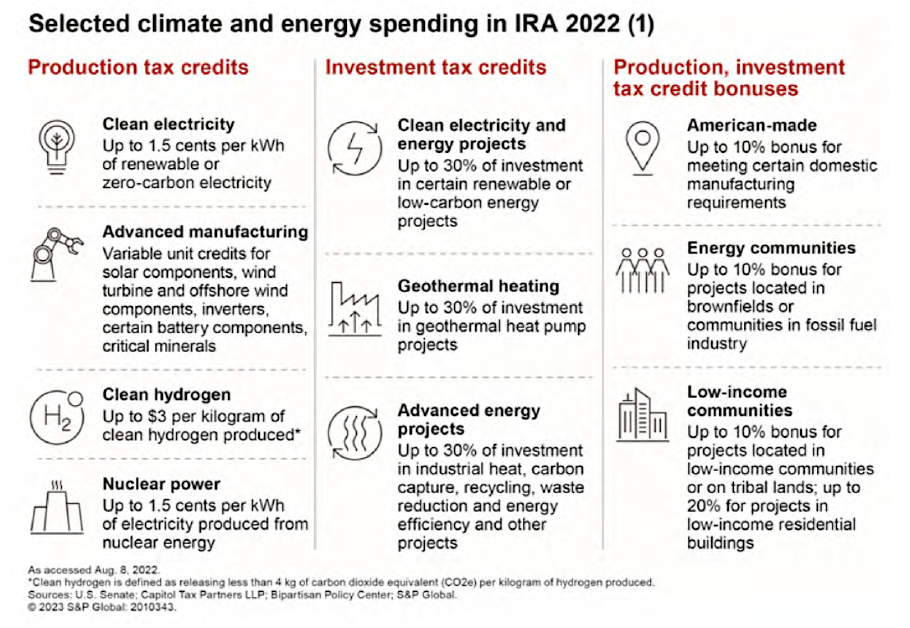

By increasing access to lower cost clean energy, improving energy efficiency, driving investment in domestic manufacturing, and diversifying supply chains, the incentives not only support domestic industries, but can also be used by other trade allies that have agreements with the US.

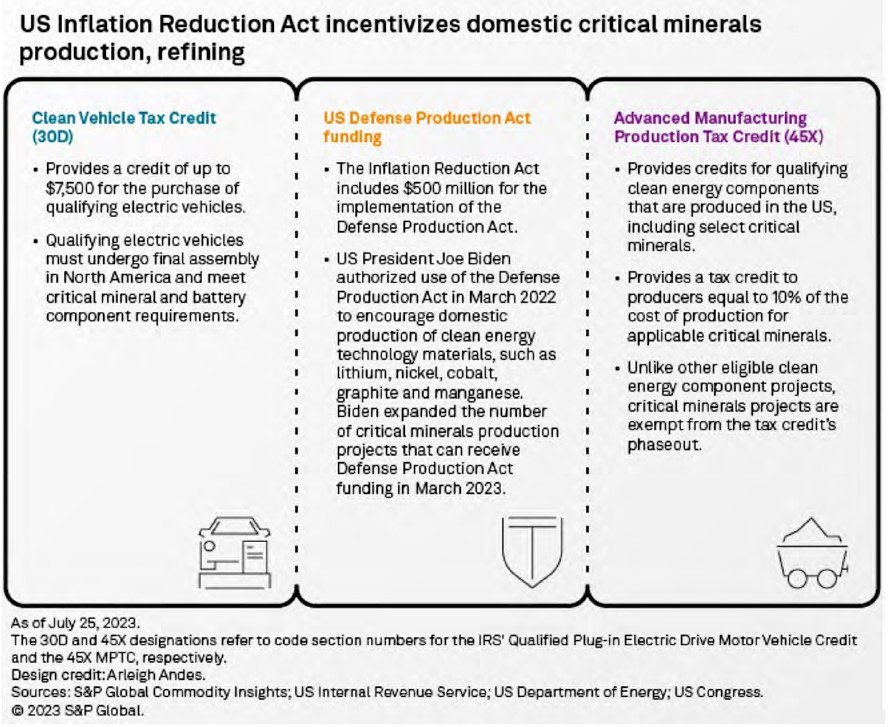

The hefty bill impacts the minerals and mining sector in two ways. It affects demand by providing large subsidies for a wide range of mineral-intensive green technologies, such as electric vehicles (EVs) and wind turbines. It also promotes mineral development on the supply side by imposing percentage requirements for mineral content from either the US or free trade agreement (FTA) countries.

For example, EVs that meet final assembly, critical mineral, and battery material sourcing requirements are eligible for a US$7,500 tax credit. There are ambiguous restrictions, however, that affect the clarity and general understanding of what vehicles do and do not qualify.

“Certainly, it’s still fairly early in terms of gauging the success of the act in stimulating supplies…there are going to be challenges to meet that domestic demand,” commented Mark Ferguson, director of Metals & Mining Research for S&P Global Market Intelligence.

Brick by brick

Despite the IRA charging ahead with more aggressive legislation to improve the domestic energy scene, tighter regulations are fast approaching and causing consternation.

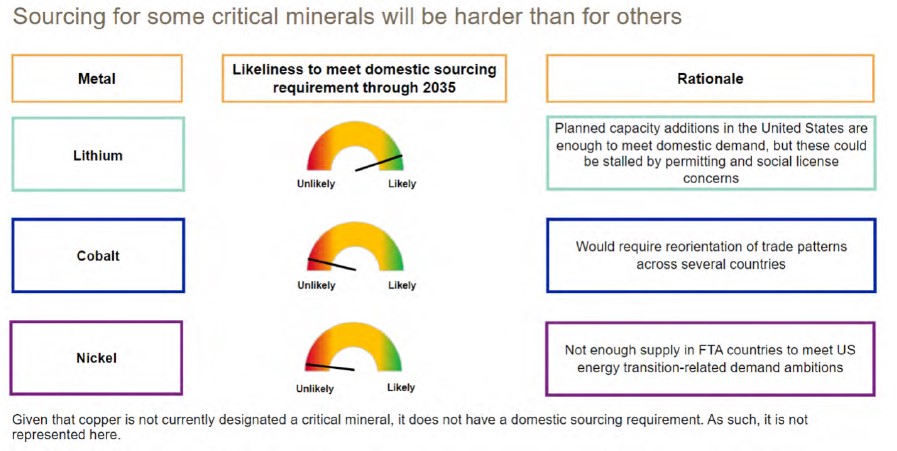

For a new EV purchase to qualify for IRA tax credits in 2024, 50% of the critical minerals in its battery (by value) must meet sourcing requirements; by 2027 that amount will become 80%. These are numbers that many companies will struggle to attain with metals like cobalt and nickel predominantly coming from non-FTA countries. Even metals that can mostly be acquired domestically or in FTA countries, like lithium, may need to be processed in countries like China due to its heavy monopoly on the different technologies necessary at each stage of production.

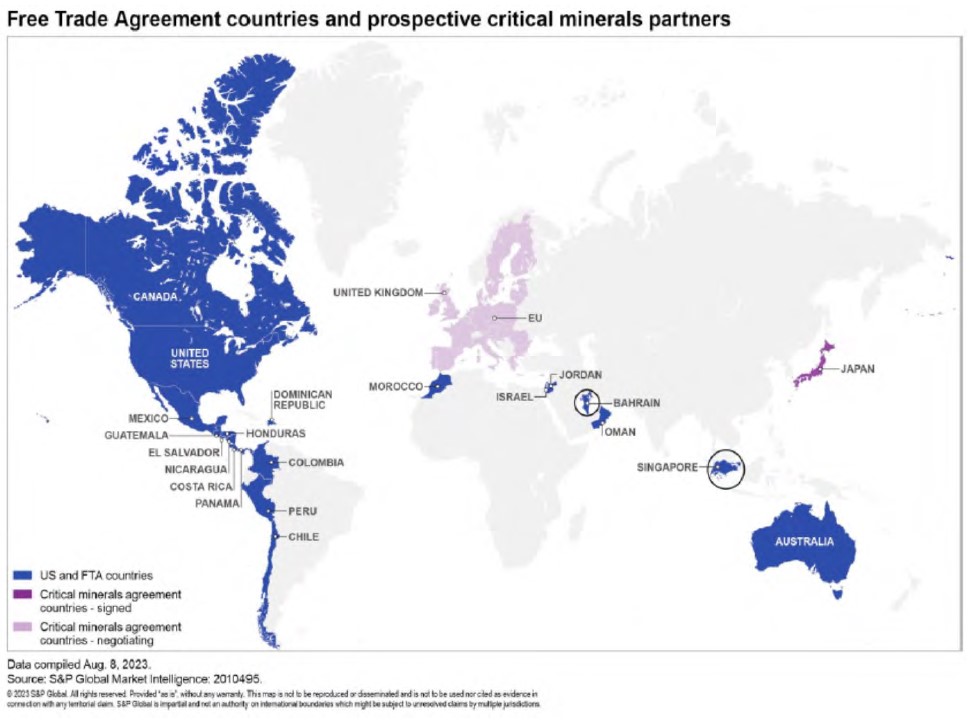

The US currently has FTA agreements with over 20 countries, including Australia, Bahrain, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, the Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Israel, Japan, Jordan, South Korea, Mexico, Morocco, Nicaragua, Oman, Panama, Peru, and Singapore.

These countries help connect gaps in the minerals supply chain and have steadily been increasing over the past year since the act was put into action, with many wanting to capitalize on the large investment package. Experts like those at S&P believe the effectiveness of the IRA hinges on its ability to secure minerals.

“[In November], the US and Indonesia started discussing ways for Indonesia to become a free trade partner,” said Ferguson. “I think there are policies that are emerging that will impact trade flows across the world and could incentivize additional supply to come on stream to feed US markets, and thereby capitalize on some of the subsidies and incentives that come along

with the IRA.”

The main issue stems from when minerals or technology are borrowed from a country that the US government dubs a foreign entity of concern (FEOC). Countries that are FEOC could be naturally excluded from any type of subsidies or incentives, even if partnered with an American company.

Enter Ford Motor Company (NYSE: F), who is currently in a quagmire over its licence to technology from Chinese battery manufacturer CATL in Ford’s US battery plants and whether this will meet IRA tax credit standards.

Under US law, a FEOC falls under one of five categories, of which the most relevant concerns a foreign entity “owned by, controlled by, or subject to the jurisdiction or direction of a government of a foreign country that is a covered nation.” Covered nations being North Korea, China, Russia, and Iran.

While the car company is still awaiting “final language” from the US Treasury on whether batteries made using Chinese technology will qualify for tax credits as they have not confirmed this exact interpretation in relation to the IRA, company executives have cited the IRA as a key influence on creating the plant in the past.

Additionally, Ford recently scaled back its EV battery plant commitment from US$3.5B down to an approximate US$2B after a two month pause in construction, however the company remains optimistic. Ford spokesman Mark Truby commented to reporters, “We are confident in terms of IRA benefits.”

EV material take over

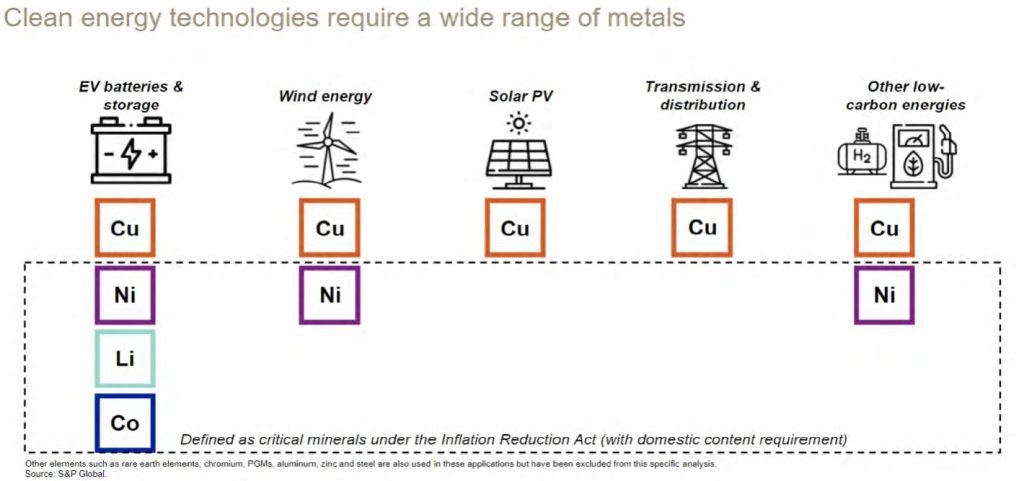

Clean energy technologies, as well as key components such as magnets and semiconductors, rely on several minerals, including copper, lithium, nickel, cobalt, graphite, and rare earths to meet net zero goals.

The International Energy Agency predicts demand for these metals to rise by 40–90% over the next 20 years, requiring investments of anywhere from US$360B to US$450B on the mining side and US$90B to US$210B in processing capabilities globally by 2030.

While the US Department of Energy qualifies a high number of these minerals as critical, including several others (aluminum, dysprosium, gallium, iridium, lithium, magnesium, natural graphite, neodymium, platinum, praseodymium, terbium, silicon, and silicon carbide), they are not all equal.

A whopping 76% of post-IRA investment has gone to domestic battery manufacturing, which focuses mainly on battery materials to support (slow but steady) increasing EV demand.

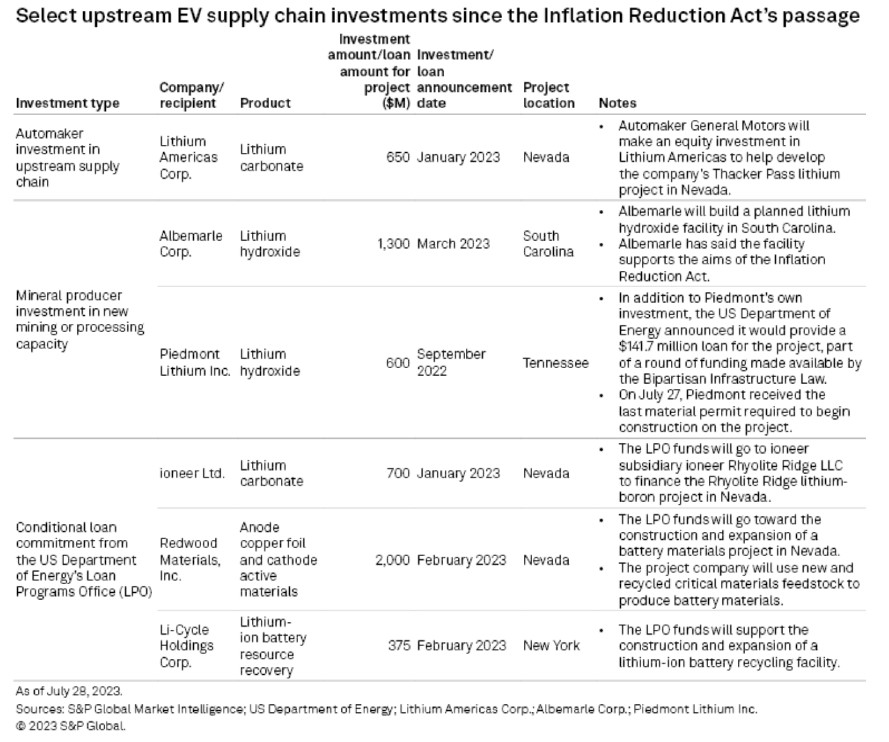

The IRA has increased overall demand for cobalt, nickel, lithium, and copper each by about 12-15% compared to pre-IRA demand, and the looming threat of a critical mineral shortage has compelled automotive companies to actively engage in the mining sector. Car companies are now acting as both investors and customers, financially supporting mining operations and guaranteeing the purchase of extracted materials.

In August, Piedmont Lithium Inc. (NASDAQ: PLL) marked a significant milestone with its first commercial shipments from its North American Lithium mine, signifying a shift from a developer to producer. Piedmont currently has an offtake agreement with EV giant Tesla until the end of 2025, where its lithium will be purchased based on average market lithium prices.

“For the last seven years, Piedmont Lithium has focused on developing a supply of crucial lithium resources, and we are excited to begin generating revenue and cash flow as we see our plans come to fruition,” said Piedmont president and CEO Keith Phillips. “Our products will help our customers meet the requirements of the IRA and, in turn, the growing demands of the US EV and battery supply chains.”

Lithium Americas Corp. (NYSE: LAC | TSX: LAC), is also focused on advancing lithium projects, with assets in Argentina and the US. Its US mine, Thacker Pass, has commenced construction and is targeting first production in the second half of 2026, soon set to be the second operating lithium mine in the country and has an agreement with automaker GM after a US$650M investment.

Even oil giant, Exxon Mobil, has started a new US$60B venture into lithium, with an announcement to set up a facility in Arkansas to produce the white metal for future EVs as early as 2027.

This trend underscores the recognition outside of the typical mining industry investor that increased involvement is necessary to secure a stable supply of crucial battery minerals for the growing demand of EVs and battery supply chains.

Copper, however, is not applicable as a critical mineral under the IRA, despite its importance as a fundamental green metal across the board.

The IRA is based on US Geological Survey guidelines, which requires a higher threshold of need compared to that of the Department of Energy. While it may soon be deemed necessary, its status has not yet been adjusted.

This lack of IRA support will likely affect investment prospects into copper in the short to midterm in comparison to other battery metals.

Despite lacking official designation, copper – like nickel, lithium, and cobalt – will have a persistent struggle to match demand with supply that meets the IRA’s requirements.

Past the first goal post

Legislation such the IRA is not sufficient to reach US decarbonization goals alone. There are still concerns regarding its effects in relation to advancements in green technology, securing supply, EV penetration, sustainable sourcing, and expediting permitting.

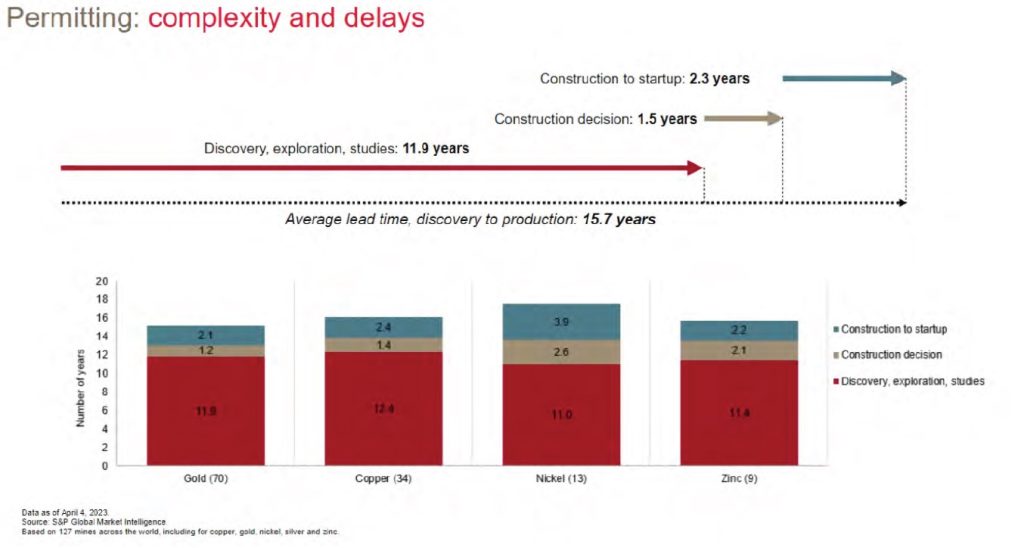

The US legal and permitting system poses a significant obstacle in preventing the act’s efficiency. A major discovery today likely would not be a productive mine until 2040 or after. Further, large and complex projects in politically sensitive areas can take even longer. More work will need to be done to expedite American permitting and project times to make the IRA truly effective in the long run.

Elections will also have an effect. Republicans have deemed support for EVs and the greater green energy transition as largely unnecessary. If their party wins the presidential election in 2024, there could be a restructuring of the IRA or transfer of funding for other purposes.

Additionally, there is growing concern over material sourcing. There have been complaints on the business end that if the US chooses to establish an FTA with Indonesia, it sends the wrong message for countries with cleaner nickel. If more expensive and clean options are chosen, however, then electric cars and green technology could become unaffordable for the average family, further stalling ambitions of increasing EV penetration.

While the IRA may be designed to address economic concerns, it has had a multifaceted impact on the mining sector in the past year. The vagueness surrounding its “foreign entity of concern” restrictions has introduced a range of difficulties for multiple companies.

Mining companies will need to navigate the evolving economic landscape, leveraging the advantages provided by the act to the best of their abilities while addressing any hurdles that may arise. Achieving a balance between safeguarding national interests and providing clear, actionable guidelines will be essential to promoting the green energy transition.

Policymakers will need to address outstanding concerns like lengthy permitting times if domestic mineral projects are to ensure legislation achieves its intended goals.