With the golden anniversary of the closure of the gold window, and the massive expansions in some nations’ balance sheets since the start of 2020, we thought that before looking at the current position it might be of interest to run through a very short potted history of the gold standard and how it worked. This is not an argument for the reinstatement of the gold standard; far from it. It is intended more to be an illustration of the former régimes, a comparison with the current position, and what we may expect in the medium term. This culminates in an assessment of two possible economic scenarios and what they might mean for gold over the period.

On 15 August 1971 President Richard Nixon closed the Gold Window, and thus direct gold-dollar convertibility, as he attempted to address the balance of payments deficit that the U.S. was running. The Bretton Woods Agreement, which in 1944 brought the IMF and the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (latterly the World Bank) into being and which was aimed at improving terms of international trade, essentially devised a new gold standard in which Bretton Woods members’ currencies would be tied to the dollar, but on an adjustable basis, while the dollar in turn would be pegged to gold. So this was not a classical gold standard which ensured a fixed exchange-rate policy over the exchange rates with gold as the ultimate currency. The original gold standard had developed in England in the 17th Century and revolved around a fixed gold price, with currencies either in the form of gold coin or redeemable in gold and with gold used as the settlement process for balance of payments deficits.

The dollar gold standard of the late 19th Century developed in the wake of the gold rushes, notably in the U.S. and Australia, and took over from silver with America enacting a bill in 1849 for the coinage of gold dollar coins in three denominations. (Britain had been using gold coins for over 100 years prior to that!). With the massive expansion in international trade over the period there was ample international demand for gold for coinage and monetary settlement, and with the Gold Standard Act of 1900 almost all the world’s nations were on the gold standard, comprising gold coinage along with commercial and official sector banks’ holdings.

During this period money supply was, by definition, controlled and exchange rates were fixed. That all fell apart as a result of the enormous financial strains imposed by the First World War and the gold price was floated, with the first London “fix” taking place on 12 September 1919. There was a return to the gold standard in 1925, but different countries adopted different policies and ultimately this failed; the collapse of the government in Britain in 1931 heralded the end of the gold standard in its then form.

Bretton Woods was a hybrid, given that there was a 1% tolerance in exchange rate bands, but rates were effectively still pegged to one another with gold as the anchor at $35/ounce. Ultimately the $35/ounce price had to give way due to massive demand for gold in Britain following the devaluation of sterling in 1967 and the “gold pool” as it was known, which comprised the U.S., Britain and the five big European nations, came under immense strain. To crown it all the Vietnam War resulted in very heavy pressure on the dollar, as well as even stronger gold demand the London market buckled under the strain and had to close for a fortnight in March 1968. While the official price of gold among central banks notionally remained at $35 until President Nixon closed the gold window, in reality the free-market price was floating from then on. The final free market price on the day that the window closed was $42.22/ounce, which is the price at which the U.S. Government still values its gold holdings. Most other countries have been marking their valuation to market for many years now.

With the massive expansion in international trade, there was ample international demand for gold for coinage and monetary settlement

Major official sector balance sheets

The history above, and the current activity among major central banks, throw up an interesting comparison. The U.S. and Europe, with histories on the gold standard, are the central banks with the most accommodative policies, while China, which was the only major nation not on the classical gold standard of the 19th to early 20th centuries, has increased its assets but at a much slower rate and has consistently stood by a policy of prudence as it does not wish to see bursting economic bubbles.

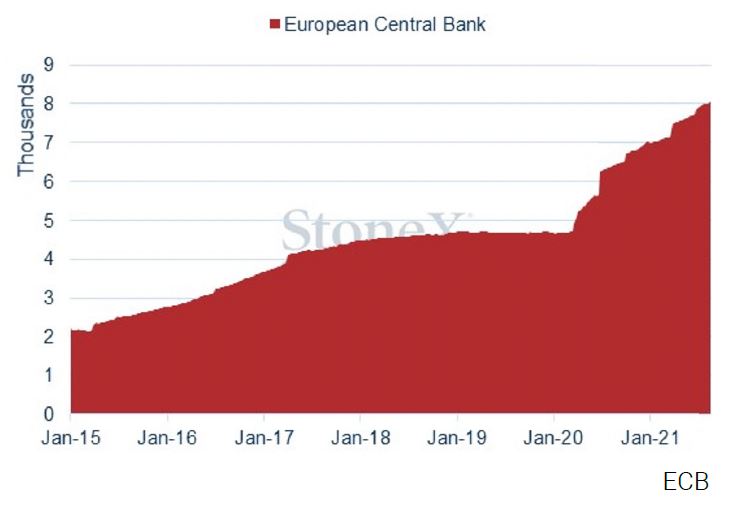

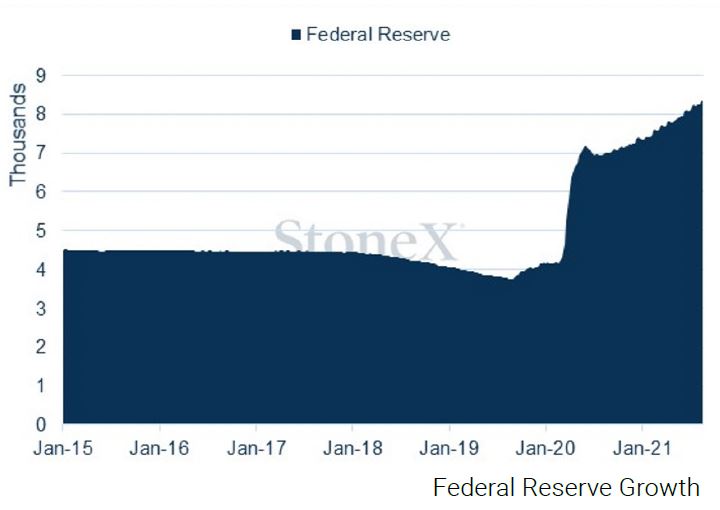

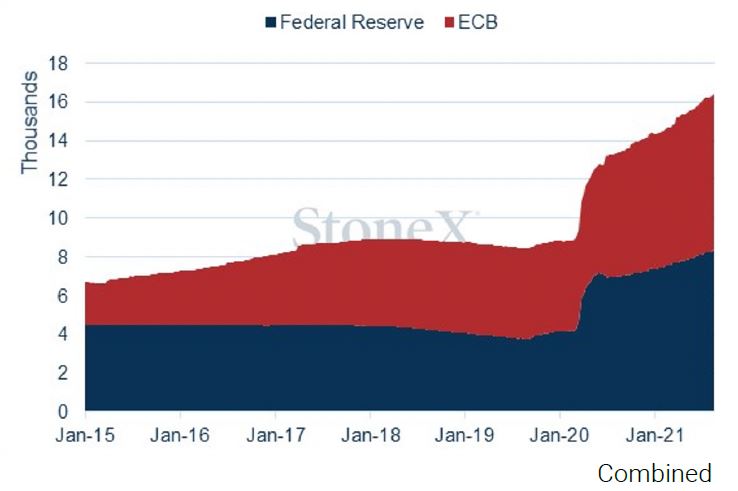

Nor, for that matter, do the Fed or the European Central Bank (ECB), but the differing nature of the politics and economic management has led to ultra-loose monetary policies. To put some numbers around this: the Fed’s reserve assets have (to late August 2021) doubled since the start of 2020, from $4.17T to $8.33T. The ECB’s reserves have expanded by 72% from $4.69T to $8.05T. Between them that is an increase of $7.5T, or 85%. To put that into context, that is equivalent to just over the combined 2020 GDP of the United Kingdom, India and Italy, and would be the world’s third largest GDP. China’s different policy has meant that the People’s Bank of China’s reserves increased by 10%, or $0.54T, over the same period to $5.9T.

These expansions mean that there are a lot of assets looking for a home and a number of funds have already increased their exposure to commodities on the back of a) expectations for continued economic growth, looking past “transitory” factors such as supply chain bottlenecks and shortages in container traffic and b) associated inflationary pressures that may in time shift from “transitory” to “persistent”. The former is associated with a shift from recession to expansion; the latter revolves around long-term inflationary expectations.

So the key question again comes back to the outlook for monetary policy. The ECB’s recent review of its July policy meeting implies that it may be able to shift from “lower-for-longer” interest rate policy sooner than it had thought, although no decision has yet been taken. The Federal Open Market Committee meeting in mid-September will have taken place by the time we publish this piece, but at the time of writing (August 2021) the markets are already pricing in tapering beginning by the end of this year, virus permitting. Jay Powell’s remarks to the Jackson Hole symposium at the end of August pointed to tapering starting, but no date was given; interest rate rises, if and when they come, are subject to different tests from asset purchases and there is much ground to cover to reach maximum employment (i.e. unemployment at no higher than 3%) – which, along with 2% inflation, is the Fed’s Dual Mandate.

ECB, Fed Reserve growth, January 2020 to late August 2021, $M

Implications for gold

As far as gold is concerned, the key here is two-fold, both elements revolving around real interest rates.

The first is that a degree of inflation is important for the lubrication of any economy and that if the current wave does indeed turn out to be transitory then rates will remain at extremely low levels for as long as it takes for the Fed to attain its dual mandate (2% inflation and maximum unemployment – i.e. unemployment at 3% or below. With unemployment still above 5%, that could well take some time). Meanwhile real interest rates are deep into negative territory in both Europe and the U.S., which means that the risk-off plays at the moment are bonds, gold and the yen. The argument about gold incurring an opportunity cost thus goes out of the window, while the reason for negative interest rates in the first place is the need to shore up fragile economies and foster a sustainable recovery. This of itself means that the background circumstances are uncertain and carrying high risk; both arguments for holding gold.

The second is that if inflation shifts to “permanent” at levels much above 3% or 4% then the major central banks have a serious headache as there is little fiscal space anywhere and raising rates too far too fast could cause instability; the alternative is accelerating inflation, which is where inflation becomes a threat rather than a friend.

Either way it is arguable that, all other things being equal, both scenarios favour gold.