From an initial announcement in October 2018 that shook the nickel world with its audacity – a 50Kt Ni/a high-pressure acid leach (HPAL) plant was to be built in Indonesia for US$700M and would be operating by sometime in 2019. The proposed development was to be located in the Morowali Industrial Park and developed by a joint venture company QMB New Energy Materials held through Tsingshan, GEM, CATL, and Hanwa. The fact that Tsingshan was involved was what made the announcement so concerning for the nickel world. The company had a phenomenal track record of developing NPI capacity at a low capital cost and rapidly – could it do the same with HPAL? The implementation of which the “West” had tried and was viewed as having quite spectacularly failed to succeed.

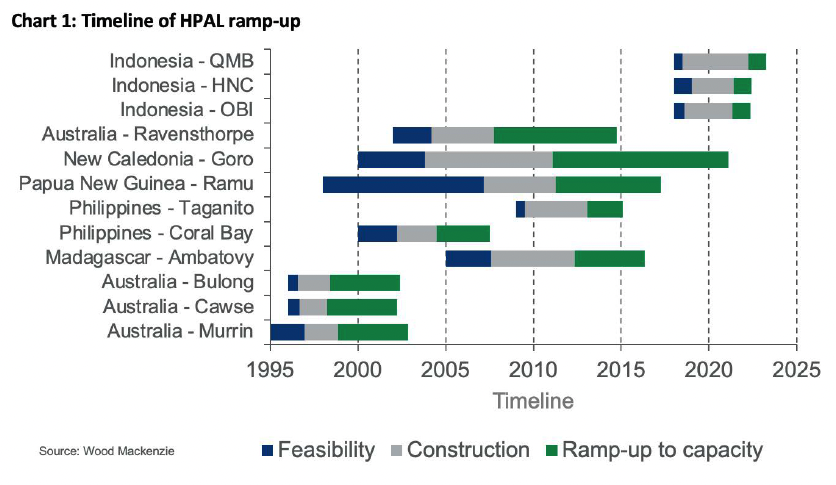

While certain things conspired to delay QMB in its development, not least COVID-19, two new HPAL operations commenced production in Indonesia in 2021, and QMB is commissioning at the time of writing. The usual phases of development, namely feasibility, approval, construction, and commissioning have taken place in record time, meaning that 150Kt of nickel-in-MHP (mixed hydroxide precipitate) capacity has been commissioned in Indonesia faster than ever before. So, yes, if not Tsingshan specifically, China could “do” HPAL quicker and cheaper than the West!

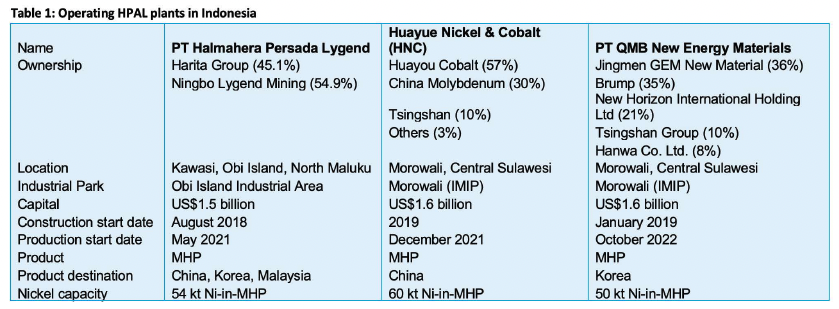

The new generation of Indonesian HPAL operations are being constructed at well under the eyewatering capital cost budgets of the previous generation of plants such as Goro (US$5.9B) in New Caledonia, Ambatovy (US$5.7B) in Madagascar, Ramu (US$2.1B) in Papua New Guinea, and Ravensthorpe ($US2.1B) in Australia. Capital costs for PT Halmahera Persada Lygend on Obi Island, North Maluku, Huayue Nickel & Cobalt (HNC) and PT QMB New Materials, both located in Morowali, Central Sulawesi have all come in under US$1.5B for ca. 50 t/a Ni-in-MHP. To put this into context, the average for Indonesia has been ca. US$30-35,000 per annual tonne of nickel, compared to an average of closer to US$100,000 per annual tonnes of nickel of the western built plants.

So why have the Indonesian plants been able to succeed where others have failed? And why have these plants been able to ramp-up to capacity in less than 12 months compared to an average of five years in the West? Well one of the key factors in accelerating these projects has been Chinese investment, but more importantly Chinese know-how. The new plant designs were based on knowledge obtained from the development and operation of the Metallurgical Corporation of China’s (MCC) Ramu operation in PNG. And why not? Although Ramu took six years to get to nameplate capacity, since then it has been operating at or above nameplate.

Chinese investment and know-how

The China ENFI Engineering Corporation (ENFI) is the key technical provider at PT Halmahera Lygend on Obi Island. ENFI, which is a subsidiary of the Metallurgical Corporation of China (MCC), has drawn on its experience from designing the Ramu plant and has adopted a very similar flowsheet for the Obi Island facility. Both Ramu (which was constructed in 2003) and Obi use three-stage preheating + autoclave + three-stage flash technology, as well as using a high-steam high-leaching rate to achieve recoveries of around 85% nickel and cobalt in MHP. The application of a tested and continuously improved flowsheet has allowed the Obi operation to ramp up to nameplate capacity in only 12 months and we are seeing a similarly impressive same accelerated ramp-up at Huayue Nickel & Cobalt (HNC) at Morowali in Central Sulawesi.

In addition to adopting proven technology and flowsheets, the new Indonesian HPAL plants have benefitted from being constructed in well-established industrial parks. Both Huayue Nickel & Cobalt (HNC) and PT QMB New Energy Materials are located within the Morowali Industrial Park (IMIP), which first started operating in 2015, producing nickel pig iron (NPI), and stainless steel. Both HNC and QMB have been able to leverage off the existing infrastructure and labour availability, as well as from the established ore supply routes, which have been tried and proven for saprolite ore for NPI smelting. Although much smaller scale, Lygend benefitted from being constructed at a brownfield site with existing NPI production.

The addition of the HPAL processing of limonite ore in Indonesia was an obvious choice given that the lower grade limonite ore needs to be removed after any overburden material to access the higher grade saprolite ore already used for smelting into NPI and more recently nickel matte. The move to HPAL processing has also been supported by the Indonesian government as part of its desire to diversify into the battery sector.

Indonesia is looking to establish itself as a battery hub with US$15B already committed to setting up end-to-end value chain projects, with companies such as LG Energy Solutions and CATL. Proposed future limitations to the export of matte and MHP (and indeed NPI) are aimed at forcing more in-country development of these value-chain projects.

More HPAL to come, but at what cost?

In July 2022 the Indonesian Nickel Miners Association (APNI) outlined that in addition to the three operating HPAL plants, another seven (five in Sulawesi) were at various stages of development. While HPAL has a lower energy intensity than laterite smelting (and therefore a lower CO2e footprint), it does create considerably more waste than nickel smelting. It is estimated that for every tonne of nickel produced via HPAL around 1.4 – 1.6t of waste is also produced. Tailings disposal is particularly challenging to deal with in environments such as Sulawesi where there is limited space for large dams due to the island’s topography, thick vegetation, and high rainfall, plus the area is seismically active.

At Ramu in Papua New Guinea, MCC were able to adopt deep-sea tailings disposal (DSTP). However, Indonesia has, for now, not permitted the use of deep-sea tailings disposal and therefore tailings need to be stored on land.

The outlawing of DSTP was a ruling which also meant that the HPAL projects were delayed somewhat while alternatives were found. The requirement for land-based tailings disposal also added to the capital costs.

On land options include the dry stacking of tailings, using tailings as backfill in mines and building conventional tailings dams. Due to rainfall, the potential for dry stacking is difficult and costly, but by building a conventional tailing dam with very little hard-rock available to secure its walls, there is always a risk of collapse.

At PT Halmahera Persada Lygend tailings are currently being treated as backfill to the mining operations, and at HNC (and likely at QMB), dry stacking is being investigated. Both methods are high cost when compared with DSTP but are far more palatable from an environmental perspective.

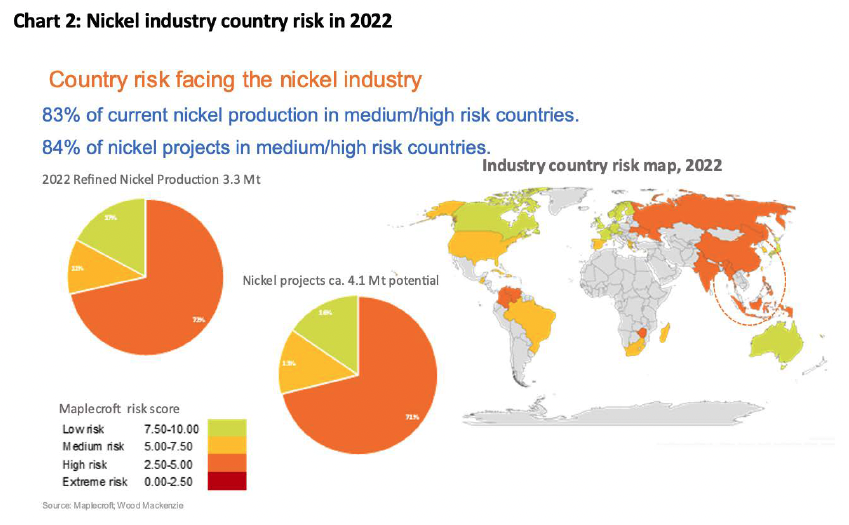

Future nickel supply is dependent on Indonesia despite the risk

In 2022, Wood Mackenzie estimates that 1.5 Mt of nickel will come from Indonesia’s NPI, matte, and HPAL operations, accounting for around 47% of total global production. By the end of the decade this proportion is expected to expand to 55%, which is remarkable given the country’s share was less than 7% in 2015. Moreover, future nickel supply for both the battery sector and stainless-steel sectors will be dependent on nickel sourced from Indonesia. The success of the new generation of HPAL operations will be largely linked to how the country deals with the waste generated from these facilities. If this is done well, both the environment and the Indonesian people will benefit. Quite the opposite if the approach turns out to be inadequate.

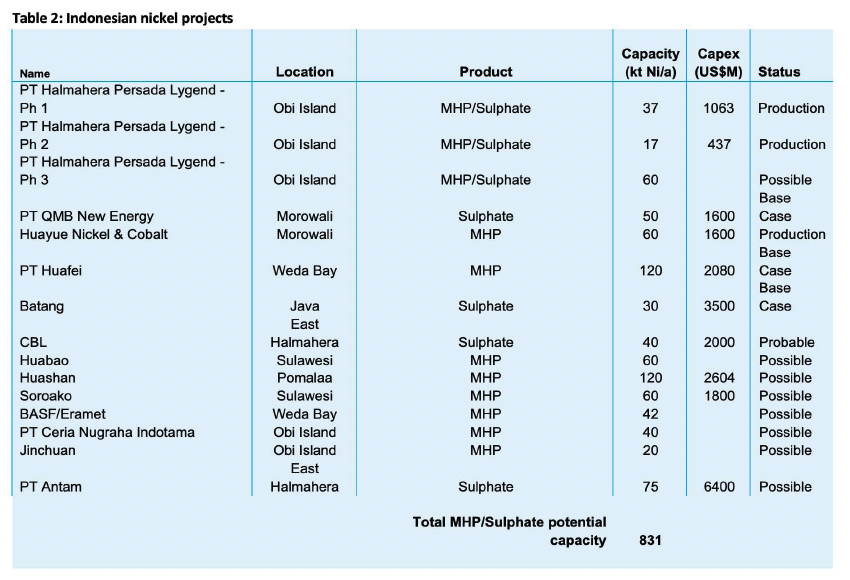

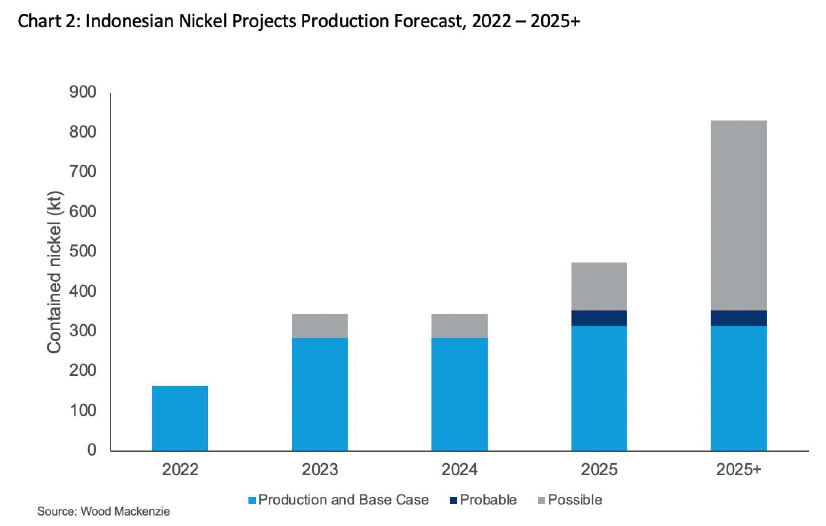

Indeed, there is little doubt that Chinese investment in HPAL operations in Indonesia will result in more intermediate (MHP, nickel sulphate) production given the success of the first two plants. As the table and chart (below) show, potential intermediate production could increase to 831Kt/y Ni by 2025. Assuming an ore grade of 1.1% Ni and 85% recovery, the ore requirement is 88.8Mt/y, which will generate 133Mt of waste per year. So the question around the expansion of HPAL technology is whether the waste can be disposed of in a safe manner, or will it be geography that limits their development rather than technology?

Comments 3