Many 1850s miners operated individually or in syndicates; most fields were covered by a patchwork of small licenses and a multitude of different owners. Any sort of large-scale co-ordinated mining and processing approach was thwarted before it could begin by a lack of central ownership. This was not resolved for decades.

2. 2000s: the revival that didn’t

Investors rushed to Victoria in the early 2000s, smitten with potential rejuvenation of the once mighty Bendigo and Ballarat gold fields (the concepts having kicked off a decade earlier). These fields were amalgamated under single owners who envisaged globally significant gold production from Victoria’s largest historic producing fields; feasibility studies forecast gold production up to 250kozpa at Ballarat, and over 700kozpa at Bendigo. Investor interest propelled the companies, Bendigo Mining and Ballarat Goldfields, to become the third and fourth-largest-capitalized, Australian-focused gold companies on the ASX in 2005.

For gold in Victoria, business was booming as evidenced by a substantial jump in the proportion of Australian exploration expenditure diverted into the state. Victoria accounted for 1.5% of exploration spend nationwide in 1991, and by 2004 it was over 10%. This surge was motivated to no small extent by the companies themselves raising and deploying exploration funds, as well as commercial imitators seeking a modicum of the share price success.

Neither project was a production success, and both dramatically underperformed the scale of gold production envisaged. Both gold fields feature geology which is notoriously challenging to estimate owing to extremely nuggety gold. As it turns out, studies for both projects over-estimated the gold grade and hence contained gold.

Neither project outcome changed the gold prospectivity of Victoria. But as spectacular failures for investors, gold in Victoria took on the smell of torched capital that lasted a decade. Victoria’s share of national exploration expenditure plummeted.

We should not overlook the success story of the period. The discovery of Golden Gift in 1999 at the Stawell Gold Mine, the bastion of long-term economic gold production in Victoria, would surely have set pulses racing. But the mine was in private ownership, a format that did not accommodate stock market speculators.

3. 2015: Fosterville – ugly duckling to swan (lode)

For well over a century, Fosterville (as far as gold projects go) was hard work. 28koz gold was produced between 1894 and 1903 before modern mining commenced in 1991 with an open pit feeding a heap leach, then a process plant was added in 2005 to treat sulphide ore. Fortune was reversed with the spectacular discovery of the extremely high-grade Swan Lode in 2017, and elevated Fosterville to the highest-grade gold mine in the world. Consequently, materially more gold has been produced by the project since 2017 than in its entire (collected) previous two and a half producing decades.

The recent history of Fosterville has been everything that the rejuvenation of Ballarat and Bendigo was not – namely, extremely profitable – and has rejuvenated exploration in Victoria, which is hot again. Victoria’s share of Australian exploration expenditure hit an all-time low of 0.95% in 2012, when mining markets were roaring but Victoria’s appeal as a gold investment destination was overprinted by memories of Bendigo and Ballarat. Victoria now accounts for over 7% of the national exploration spend, with over A$150M spent in 2020. Stavely Minerals (ASX: SVY), the finder of copper in Western Victoria is a certain contributor to the trend, albeit relatively recently (since 2019).

Lasting impressions

Victoria’s first gold rush was epic. First movers to some fields found bountiful shallow gold, and most miners could be self-funded on small license. Gold mining activities were broad, but never large scale. The significance of the event is most easily evident in the movement of people rather than capital; the population of Victoria increased six-fold between 1850 and 1860. Discoveries were made by prospecting, not exploration, and highlighted the immense geological prospectivity which to this day is yet to be tested. Much unfinished business was left for gold exploration in Victoria, but for capital to unlock some of the geological secrets.

Far from propelling Victoria, the second rush arguably set it back. Keen investor interest was developed for the attempted rejuvenation of Bendigo and Ballarat but failure of the projects deterred investors. When Australian exploration boomed in 2007 and 2011, Victoria was avoided.

A chance discovery of wonderfully high-grade ore beneath Fosterville by a Canadian company (a smack in the face to the Australian companies who overlooked the project ?) is a genuine success that has generated substantial profits, and brought on the third rush. Victoria has been promoted strongly into a foreign market and attracted substantial investment – discoveries cost money, and with investor interest overlapping with a great success story, Victoria is better positioned now for gold exploration than any time in the last hundred years.

References

Phillips G.N., Hughes M.J., Arne D.C., Bierlein F.P., Carey S.P., Jackson P. & Willman C.E. 2003. Gold. In Birch W.D. ed. Geology of Victoria, pp 377-433. Geological Society of Australia Special Publication 23. Geological Society of Australia (Victoria Division)!

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

After a grand start, by 1870 Victorian gold production was in decline. A brief and only moderate revival centred on 1900, modern gold production has only ever been a small fraction of that of the 1850s. A large proportion of gold produced in Victoria was alluvial – it was extracted from modern or ancient water courses. Many workings were rapidly exhausted, and miners moved on, curtailing Victoria’s longevity as a gold producing heavyweight. Alluvial workings did lead to primary hard rock sources which were also worked, some for decades, but mostly for less substantial gold production.

Many 1850s miners operated individually or in syndicates; most fields were covered by a patchwork of small licenses and a multitude of different owners. Any sort of large-scale co-ordinated mining and processing approach was thwarted before it could begin by a lack of central ownership. This was not resolved for decades.

2. 2000s: the revival that didn’t

Investors rushed to Victoria in the early 2000s, smitten with potential rejuvenation of the once mighty Bendigo and Ballarat gold fields (the concepts having kicked off a decade earlier). These fields were amalgamated under single owners who envisaged globally significant gold production from Victoria’s largest historic producing fields; feasibility studies forecast gold production up to 250kozpa at Ballarat, and over 700kozpa at Bendigo. Investor interest propelled the companies, Bendigo Mining and Ballarat Goldfields, to become the third and fourth-largest-capitalized, Australian-focused gold companies on the ASX in 2005.

For gold in Victoria, business was booming as evidenced by a substantial jump in the proportion of Australian exploration expenditure diverted into the state. Victoria accounted for 1.5% of exploration spend nationwide in 1991, and by 2004 it was over 10%. This surge was motivated to no small extent by the companies themselves raising and deploying exploration funds, as well as commercial imitators seeking a modicum of the share price success.

Neither project was a production success, and both dramatically underperformed the scale of gold production envisaged. Both gold fields feature geology which is notoriously challenging to estimate owing to extremely nuggety gold. As it turns out, studies for both projects over-estimated the gold grade and hence contained gold.

Neither project outcome changed the gold prospectivity of Victoria. But as spectacular failures for investors, gold in Victoria took on the smell of torched capital that lasted a decade. Victoria’s share of national exploration expenditure plummeted.

We should not overlook the success story of the period. The discovery of Golden Gift in 1999 at the Stawell Gold Mine, the bastion of long-term economic gold production in Victoria, would surely have set pulses racing. But the mine was in private ownership, a format that did not accommodate stock market speculators.

3. 2015: Fosterville – ugly duckling to swan (lode)

For well over a century, Fosterville (as far as gold projects go) was hard work. 28koz gold was produced between 1894 and 1903 before modern mining commenced in 1991 with an open pit feeding a heap leach, then a process plant was added in 2005 to treat sulphide ore. Fortune was reversed with the spectacular discovery of the extremely high-grade Swan Lode in 2017, and elevated Fosterville to the highest-grade gold mine in the world. Consequently, materially more gold has been produced by the project since 2017 than in its entire (collected) previous two and a half producing decades.

The recent history of Fosterville has been everything that the rejuvenation of Ballarat and Bendigo was not – namely, extremely profitable – and has rejuvenated exploration in Victoria, which is hot again. Victoria’s share of Australian exploration expenditure hit an all-time low of 0.95% in 2012, when mining markets were roaring but Victoria’s appeal as a gold investment destination was overprinted by memories of Bendigo and Ballarat. Victoria now accounts for over 7% of the national exploration spend, with over A$150M spent in 2020. Stavely Minerals (ASX: SVY), the finder of copper in Western Victoria is a certain contributor to the trend, albeit relatively recently (since 2019).

Lasting impressions

Victoria’s first gold rush was epic. First movers to some fields found bountiful shallow gold, and most miners could be self-funded on small license. Gold mining activities were broad, but never large scale. The significance of the event is most easily evident in the movement of people rather than capital; the population of Victoria increased six-fold between 1850 and 1860. Discoveries were made by prospecting, not exploration, and highlighted the immense geological prospectivity which to this day is yet to be tested. Much unfinished business was left for gold exploration in Victoria, but for capital to unlock some of the geological secrets.

Far from propelling Victoria, the second rush arguably set it back. Keen investor interest was developed for the attempted rejuvenation of Bendigo and Ballarat but failure of the projects deterred investors. When Australian exploration boomed in 2007 and 2011, Victoria was avoided.

A chance discovery of wonderfully high-grade ore beneath Fosterville by a Canadian company (a smack in the face to the Australian companies who overlooked the project ?) is a genuine success that has generated substantial profits, and brought on the third rush. Victoria has been promoted strongly into a foreign market and attracted substantial investment – discoveries cost money, and with investor interest overlapping with a great success story, Victoria is better positioned now for gold exploration than any time in the last hundred years.

References

Phillips G.N., Hughes M.J., Arne D.C., Bierlein F.P., Carey S.P., Jackson P. & Willman C.E. 2003. Gold. In Birch W.D. ed. Geology of Victoria, pp 377-433. Geological Society of Australia Special Publication 23. Geological Society of Australia (Victoria Division)!

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

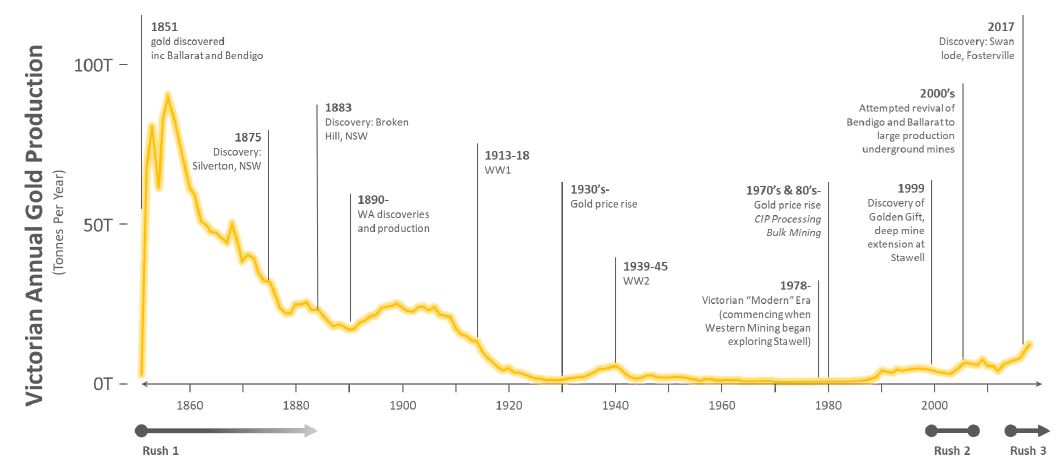

The Australian state of Victoria has produced over 80Moz of gold. A great deal of that was found in the gold rush that commenced in the early 1850s – the first large scale rush to occur in Australia. This event was slow to fade but left a tantalizing suggestion of hidden riches that remain. Classical gold rushes are now confined to history under modern day society in Victoria and instead take place in the investment market. There have been two further, modern-day, “investor” rushes to Victoria that show the romance sparked by the 1850s finds has never completely faded.

1. 1850s: first and biggest?

The first reported gold discovery in Australia was in New South Wales in 1851. Discovery of gold in Victoria quickly followed the same year and discovery of successive new gold fields followed within weeks, resulting in very significant workings (and remaining grand townships), such as Bendigo and Ballarat. The heyday for Victoria saw the fledgling state account for just shy of 50% of global gold production during the 1850s and 1860s. Melbourne was transformed financially and demographically; gold well and truly put Victoria on the map.

After a grand start, by 1870 Victorian gold production was in decline. A brief and only moderate revival centred on 1900, modern gold production has only ever been a small fraction of that of the 1850s. A large proportion of gold produced in Victoria was alluvial – it was extracted from modern or ancient water courses. Many workings were rapidly exhausted, and miners moved on, curtailing Victoria’s longevity as a gold producing heavyweight. Alluvial workings did lead to primary hard rock sources which were also worked, some for decades, but mostly for less substantial gold production.

Many 1850s miners operated individually or in syndicates; most fields were covered by a patchwork of small licenses and a multitude of different owners. Any sort of large-scale co-ordinated mining and processing approach was thwarted before it could begin by a lack of central ownership. This was not resolved for decades.

2. 2000s: the revival that didn’t

Investors rushed to Victoria in the early 2000s, smitten with potential rejuvenation of the once mighty Bendigo and Ballarat gold fields (the concepts having kicked off a decade earlier). These fields were amalgamated under single owners who envisaged globally significant gold production from Victoria’s largest historic producing fields; feasibility studies forecast gold production up to 250kozpa at Ballarat, and over 700kozpa at Bendigo. Investor interest propelled the companies, Bendigo Mining and Ballarat Goldfields, to become the third and fourth-largest-capitalized, Australian-focused gold companies on the ASX in 2005.

For gold in Victoria, business was booming as evidenced by a substantial jump in the proportion of Australian exploration expenditure diverted into the state. Victoria accounted for 1.5% of exploration spend nationwide in 1991, and by 2004 it was over 10%. This surge was motivated to no small extent by the companies themselves raising and deploying exploration funds, as well as commercial imitators seeking a modicum of the share price success.

Neither project was a production success, and both dramatically underperformed the scale of gold production envisaged. Both gold fields feature geology which is notoriously challenging to estimate owing to extremely nuggety gold. As it turns out, studies for both projects over-estimated the gold grade and hence contained gold.

Neither project outcome changed the gold prospectivity of Victoria. But as spectacular failures for investors, gold in Victoria took on the smell of torched capital that lasted a decade. Victoria’s share of national exploration expenditure plummeted.

We should not overlook the success story of the period. The discovery of Golden Gift in 1999 at the Stawell Gold Mine, the bastion of long-term economic gold production in Victoria, would surely have set pulses racing. But the mine was in private ownership, a format that did not accommodate stock market speculators.

3. 2015: Fosterville – ugly duckling to swan (lode)

For well over a century, Fosterville (as far as gold projects go) was hard work. 28koz gold was produced between 1894 and 1903 before modern mining commenced in 1991 with an open pit feeding a heap leach, then a process plant was added in 2005 to treat sulphide ore. Fortune was reversed with the spectacular discovery of the extremely high-grade Swan Lode in 2017, and elevated Fosterville to the highest-grade gold mine in the world. Consequently, materially more gold has been produced by the project since 2017 than in its entire (collected) previous two and a half producing decades.

The recent history of Fosterville has been everything that the rejuvenation of Ballarat and Bendigo was not – namely, extremely profitable – and has rejuvenated exploration in Victoria, which is hot again. Victoria’s share of Australian exploration expenditure hit an all-time low of 0.95% in 2012, when mining markets were roaring but Victoria’s appeal as a gold investment destination was overprinted by memories of Bendigo and Ballarat. Victoria now accounts for over 7% of the national exploration spend, with over A$150M spent in 2020. Stavely Minerals (ASX: SVY), the finder of copper in Western Victoria is a certain contributor to the trend, albeit relatively recently (since 2019).

Lasting impressions

Victoria’s first gold rush was epic. First movers to some fields found bountiful shallow gold, and most miners could be self-funded on small license. Gold mining activities were broad, but never large scale. The significance of the event is most easily evident in the movement of people rather than capital; the population of Victoria increased six-fold between 1850 and 1860. Discoveries were made by prospecting, not exploration, and highlighted the immense geological prospectivity which to this day is yet to be tested. Much unfinished business was left for gold exploration in Victoria, but for capital to unlock some of the geological secrets.

Far from propelling Victoria, the second rush arguably set it back. Keen investor interest was developed for the attempted rejuvenation of Bendigo and Ballarat but failure of the projects deterred investors. When Australian exploration boomed in 2007 and 2011, Victoria was avoided.

A chance discovery of wonderfully high-grade ore beneath Fosterville by a Canadian company (a smack in the face to the Australian companies who overlooked the project ?) is a genuine success that has generated substantial profits, and brought on the third rush. Victoria has been promoted strongly into a foreign market and attracted substantial investment – discoveries cost money, and with investor interest overlapping with a great success story, Victoria is better positioned now for gold exploration than any time in the last hundred years.

References

Phillips G.N., Hughes M.J., Arne D.C., Bierlein F.P., Carey S.P., Jackson P. & Willman C.E. 2003. Gold. In Birch W.D. ed. Geology of Victoria, pp 377-433. Geological Society of Australia Special Publication 23. Geological Society of Australia (Victoria Division)!