Commodities are famously a cyclical industry. While taking a risk to generalize, traditional commodity cycles begin with a demand improvement which outpaces supply, causing prices to rise to a level which incentivizes new supply, both in the short term from restarting mothballed mines or generating more scrap supply, and in the medium term by encouraging investment in new mines.

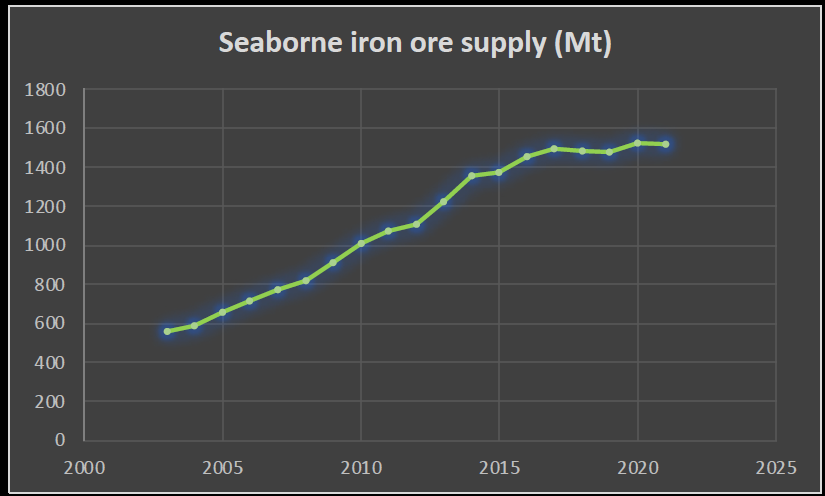

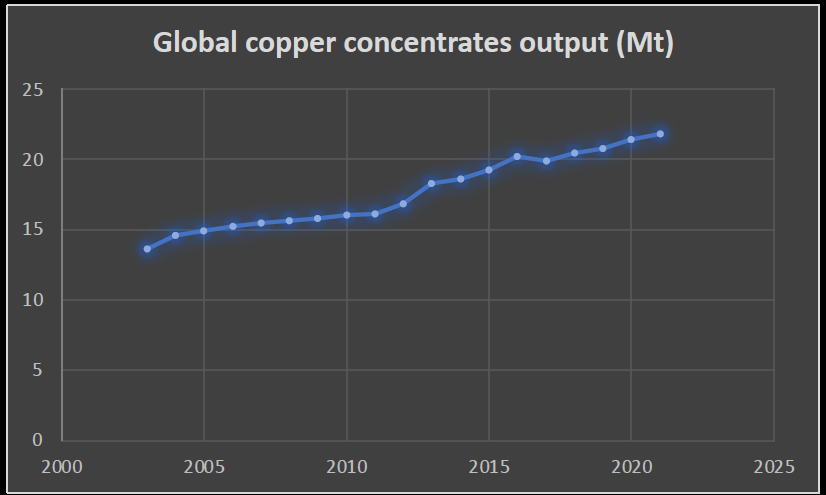

The commodities “supercycle” from 2003 to 2013, with a blip for the global financial crisis in 2008/9, resulted in an incredible expansion of supply of most commodities to meet China’s booming demand. From 2003 to 2013, global copper concentrates output rose from 13.6Mt to 18.3Mt. Iron ore seaborne supply meanwhile surged from under 600Mt to over 1.2Bt.

However, the historical mechanism of high prices encouraging exploration and new mine development appears to have broken down in recent years.

Major issues

While commodity prices have performed relatively well since 2017 through to this year, and mining companies have made considerable profits, it seems the management of the major mining companies have become more focused on returning capital to shareholders than in investing in new mine developments.

There appear to be a number of factors which have dissuaded the major mining companies from reinvesting profits in new mine developments. Since the metals price downturn of 2014/15, there has been pressure from shareholders to manage capital in a more risk averse manner, with a preference for returning profits to shareholders. The view that the China driven “supercycle” was also over at that point additionally drove companies to be more defensive of their current assets and not wanting to encourage structural oversupply when future demand drivers were becoming less certain.

Additionally an increasing focus on ESG and public relations appears to have resulted in a more risk averse management approach. Risks around local communities and environmental pressures have made greenfield projects increasingly less palatable to large companies even in their familiar home environments, let alone in jurisdictions where political stability may be more uncertain.

Further uncertainties from geopolitical risks, a world where globalization seems to be going backwards, and uncertain tax environments where governments even in traditional mining jurisdictions such as Australia and Chile have made considerable changes recently, are all combining to lessen the incentive and willingness of the major mining companies to make large scale investments in new supply.

Feeling the impact

This lack of investment since the mid-2010s is already showing up in tighter physical commodity markets today. For example, seaborne iron ore supply this year looks set to be lower than 2017 levels, despite Chinese steel output being nearly 10% higher than it was then even after accounting for the recent housing downturn. Global copper concentrates supply meanwhile has only increased to around 21.5Mt from 20.2Mt over the same timeframe.

Of course if major mining companies, with their immense profits and easy access to capital, are no longer funding investments in new mine developments, this begs the question of who will take their place. Clearly there is room for junior miners and explorers to fill this gap. However often these smaller players suffer from a lack of access to capital which can hinder their ability to deliver on new supply even if their exploration is successful.

There has often been talk of government support for mine developments, from support for rare earths and battery metals in western countries, to state owned developments by Chinese both locally and overseas. However, many of these investments themselves have still come up against problems and delays, and the idea of governments trying to pick winners and drive developments does not have a strong track record.

India is already the world’s second largest steel producer and consumer

China and India growth

Ultimately this lack of investment in new supply is going to lead to tighter commodity markets in future, resulting in higher prices for many metals especially if demand continues to grow. While the Chinese economy has seen its structural rate of metals demand growth reduce on demographic headwinds and economic reforms which involve shrinking a bloated property sector, overall global demand for most commodities will continue to rise in the years ahead. Indeed the investment levels required globally in areas such as renewable power infrastructure and electric vehicles to support global climate targets will require substantial volumes of metals as has already been well documented.

India too seems to be executing better on its infrastructure investments these days, and finally starting to live up to its potential. India is already the world’s second largest steel producer and consumer, and the world steel association recently revised their forecasts for Indian steel demand growth to 6.1% this year and 6.7% next making the country the fastest growing major steel consumer.

Even if new demand growth for commodities were to disappoint, investment in new mine supply is still needed to offset depletions of existing mines. Indeed this is already showing up as a major issue in some metals, particularly copper, where ageing mines in Chile have resulted in the countries copper output recently falling back to levels not seen since 2004, as new mining projects are seeing continual delays, while older mines are depleting faster.

Significant investment in new mine supply will be needed just to sustain current levels of global production for copper and other metals, let alone provide additional tonnage to feed incremental demand growth. Without the investment support from major mining companies however, the question is where will this supply come from, and how high will prices need to go to incentivize sufficient levels of investment?