As precious metals sector specialists, we are encouraged to see signs of life returning to the gold markets and positive developments underway among gold miners, as the industry meets the challenges to improve its relevance to generalist investors. However, gold miners must also find a way to generate sustainable returns in a sector where environmental, social, and governance (ESG) concerns are finally starting to go beyond lip service.

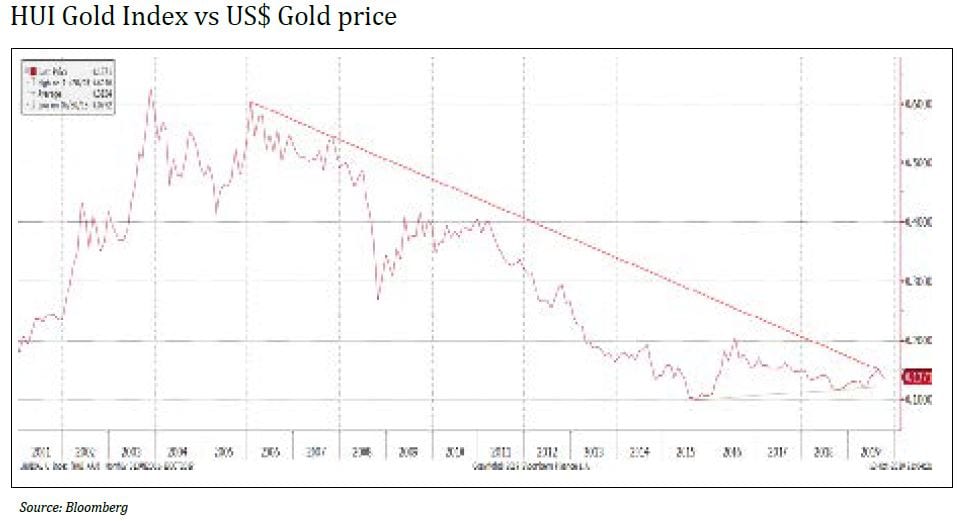

Since 2006-2007, gold shares have collectively underperformed gold, although we are starting to see signs that this trend is changing. What caused this underperformance? The downturn for gold stocks was exacerbated by over a decade of poor capital discipline when, encouraged by investors, most gold miners

positioned themselves as leveraged options on the gold price rather than as businesses trying to generate a return. Some companies are still suffering from this hangover as they continue to live with the legacy of debt, mines, and projects that have overpromised and under delivered.

It’s All About the Margin

When an investor buys a gold mining equity, they are prioritising the margin over the life of the reserves in the ground. The gold shares underperformed gold as producers lost this focus and concentrated on producing more ounces instead of more margin. This encouraged investors to sell the miners to buy the royalty companies – companies that own a fixed portion of the margin of a gold mine. These royalties are often sold by the gold miners in exchange for equity to build their mines. The reason for the outperformance of the gold royalty companies was clear: money flowed from the promise of margin to the certainty of margin.

Australian producers changed their business model – focusing on margin not ounces

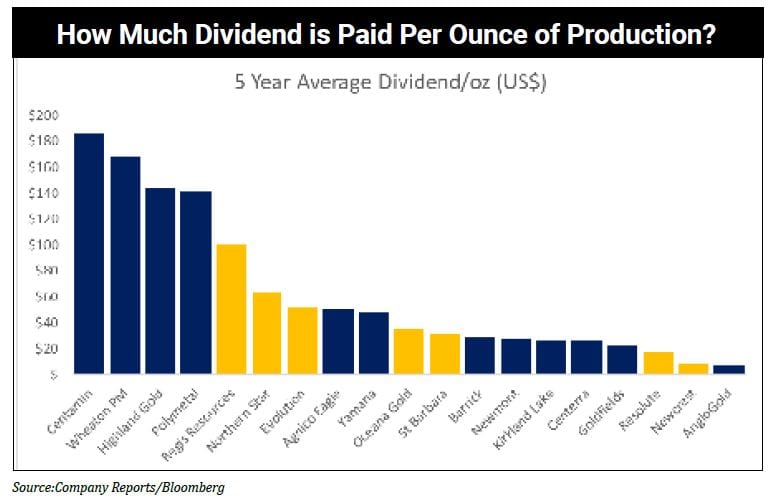

This didn’t go unnoticed in Australia. Several producers understood this and reverted to focusing on margin versus ounces, resulting in investors starting to bid up the shares of the Australian producers, effectively chasing the margin expansion. The Australian gold producers started outperforming the sector. They had a simple formula: mine gold at the lowest cost, sustain this margin, and then return some of this margin to shareholders. This is the key – returning some of the margin to shareholders (more on this later). No doubt the weaker Australian dollar also helped margins by lifting the Australian dollar gold price. Historically this margin would have been compromised to produce more ounces by lowering the cut-off grade, but, to their credit, the Australian producers focused on how they could increase their margins instead of ounces. Examples are Northern Star Resources (ASX: NST), Evolution Mining (ASX: EVN), St Barbara (ASX: SBM), Regis Resources (ASX: RRL), and of course Newcrest Mining (ASX: NCM), who, together with Randgold, really set the benchmark during the last cycle. With the increased margins, producers were able to reward shareholders and still have enough to explore and increase their vault of gold’ in the ground which, if the margin is sustained, drives the valuation of the company. Smarter exploration has revitalised what were considered tired assets; Jundee, Cowal, Gwalia Deeps come to mind.

Where To From Here?

Historically, as a bull market progresses, investors have ended up paying for the gold in the ground. So, in our opinion, today is an appropriate time to help investors understand the importance of the link between what’s in the ground, how much it costs to find an ounce, and what shareholders get paid for each ounce mined before the bulls really start running. We believe this connection is important for shareholders to understand for the following reasons:

- Assuming a producer increases its inventory of reserves, knowing what shareholders have historically been paid for each ounce of production gives investors a benchmark to quickly value those additional ounces.

- If the dividend is linked to the gold price and production and therefore profits (as in the case of Northern Star), then the rising gold price directly translates into a higher dividend income.

- Transparent and simple-to-understand metrics in businesses where we can see profitable, sustainable growth certainly clarifies the investment decision when, as Fund Managers, we are frequently bombarded with copious amounts of information from a large universe of producers.

- Metrics that are simple-to-understand and communicate can only help simplify the investment case to a wider audience than just the specialist mining funds.

Why Shouldn’t Shareholders Get a Percentage of Revenue as a Dividend?

Overwhelmingly most of the profits from the gold sector come from a handful of quality mines. The best mines generate all the wealth and the best deposits generally reveal themselves over time. These are the mines that investors should focus on. In this respect, gold mining investors Baker Steel has a policy of buying companies that predominately own the best assets and can sustain a healthy +30 percent profit margin. A third of this profit margin is earmarked to sustain the business, a third to grow the business, and as shareholders we would expect that a third of this margin should be returned to shareholders. This gives us a benchmark that a good profitable gold company should be able to return 10 percent of its revenue to shareholders. If it doesn’t, we would argue that they are really speculating. That doesn’t mean that we don’t own gold companies who don’t return 10 percent of their revenue to shareholders, but at least we understand the nature of the investment. If your gold equity investment does not pay you a dividend, ask them why they are digging the hole in the first place. If they are not and don’t plan to, you are speculating not investing!

What Does the Market Cap to Revenue Multiple Tell us?

Sustainable margins and a percentage of the revenue returned to shareholders is our first criterion. We also analyse the ratio of the annual revenue to the capitalisation of the company. As one would expect, higher margin producers trade at a higher revenue multiple, with the royalty companies (which have a guaranteed margin) trading at the largest multiple. Our rationale here is that if a producer pays us a fixed percentage of revenue (not dissimilar to a royalty), the company has a greater chance of trading at a higher multiple. As a producer is not a royalty company, we focus on the sustainability of the margin.

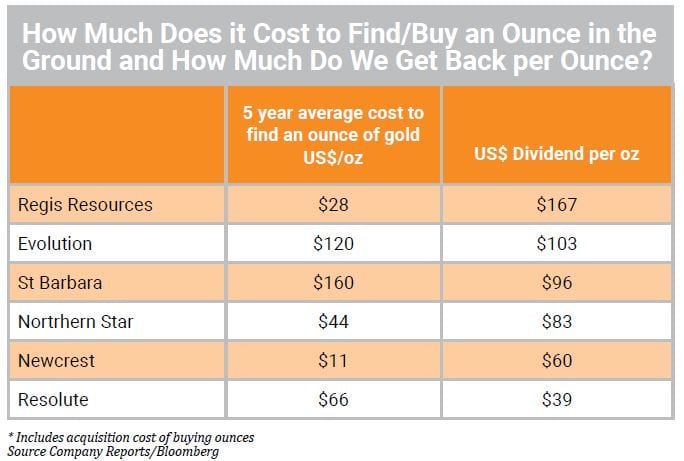

Buy Producers Who Pay More per Ounce Than It Costs Them to Find an Ounce of Gold

Our next objective is to pick companies that are poorly rated by the market in terms of multiple to revenue and look for signs showing why the market should pay more. Is the margin expanding? Are they growing their revenue? As earlier stated, we focus on the margin. For this to be sustainable, we want to buy companies with a track record of finding good quality ounces of gold that will replenish their inventory. So, another metric we favour is the five-year average cost to find an ounce of gold for a producer, compared with the average return shareholders receive for each ounce produced. Our ideal investment is a producer with sustainable margins that finds quality ounces at a lower cost than the amount returned to shareholders. Given that we are looking for producers to return 10 percent of

their revenue, we would be looking for companies that return USD 150/oz for each ounce they mine and find it for less than this.

Summary

The gold industry has made incremental improvements since the sector lows in 2015, against a backdrop of a steadily rising gold price. However, beneficial reforms have not been implemented across the board, resulting in substantial disparities between the operation and share price performance of some producers. Notaby, Australian producers have led the way in demonstrating improved capital discipline, with a focus on shareholder returns, and have consequently tended to generate share price outperformance in recent years.

It’s all about the margin, how much it costs to find an ounce of gold in the ground, and whether the shareholder gets more than it costs to find.