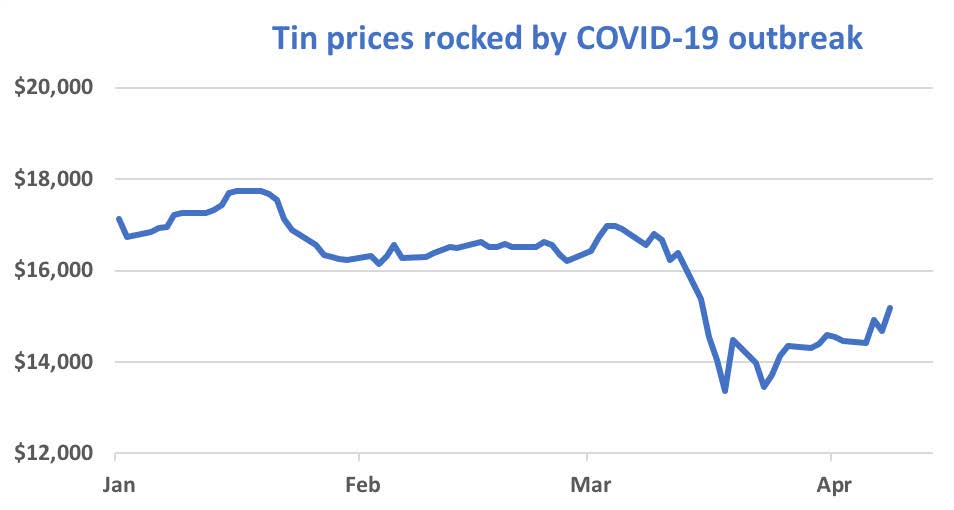

The coronavirus (COVID-19) has hit tin, like all commodities, hard. Early in the year, the London Metals Exchange (LME) price appeared to be regaining some of the ground it lost to a tumultuous year of trade wars. However, it plummeted almost 20% in just over a week as infections began to rise globally. Tin now sits at around US$ 15,000/tonne, levels not seen since the 2008-2009 Financial Crisis. While general macroeconomic decline and risk-off sentiment caused much of this decline, the virus has also disrupted the physical tin market.

Production paralysed by quarantine measures

China usually sees production and consumption fall across the first two months of the year due to Chinese New Year celebrations. Most smelters reduce their output, while some close altogether. But as China shut down to prevent the virus spreading, smelters across the country suspended production for longer. Private smelters across the country closed for several weeks, while the government owned enterprises (including Yunnan Tin), operated below full capacity.

As the measures lifted in March, problems persisted. Some workers were unable to re-enter provinces due to strict movement orders, meaning that companies that could open were running below full capacity.

Overall, China produced 13% less refined tin in the first quarter of 2020 compared to 2019. For the entire year we expect output to fall some 4%, in part due to the coronavirus. However, the Chinese tin smelting industry is still struggling to source raw materials as production from neighbouring Myanmar falls. The coronavirus has also exacerbated this. Local people operate the mines, but processing plants are generally run by Chinese workers. Those who returned to China to celebrate the New Year have struggled to cross back into Myanmar. Ore stockpiles in the country are continuing to rise, but this does not help Chinese smelters. We do not expect exports to return to normal until late May at the earliest.

Smelters outside of China are beginning to follow the same path. Smelters in particularly hard-hit countries, primarily in South East Asia and South America, have suspended production. In total, almost 5,000 tonnes of refined tin will be removed from the market by the time the current quarantine measures end – although it is likely that many of these measures will be extended.

” Combined with positive forecasts for tin in energy generation and storage, as well as automation, robotics and 5G, there is still reason to be positive on future tin demand, despite the current conditions.”

COVID-19 has also affected the concentrate market. Miners in Africa have downed tools as the combination of a low LME price and the virus have made other jobs more attractive. In Rwanda, government measures have paralysed the mining industry. For two of the world’s top ten refined tin producers, Africa is a major source of concentrate. This decline will likely lead to reduced output once they resume full-scale operations.

On top of these closures, PT Timah announced in March that it would cut production. The world’s largest producer last year could reduce exports by 20-30% while it gauges the impact of the virus on global demand. Although total Q1 exports from Indonesia rose 27% YoY, March data shows that after the announcement, sales through local exchanges fell drastically.

However, the combination of voluntary and involuntary production cuts will likely not prevent the tin market moving into a significant surplus in 2020.

Demand downturn on scale of Financial Crisis

There is very little question that this year will be a poor one for global economic growth. The question is not if, but by how much, growth will fall by. Many economists are predicting that the coronavirus recession will be on a similar scale to the 2008-2009 Financial Crisis. The same is likely true for tin.

China comprises around 45% of global tin demand. While the initial closure of solder, chemical and tinplate producers slowed demand, orders were still being filled. However, some

of these companies are reporting that they have not received new orders since they returned to work.

Outside of China, many companies were reporting strong business up to the end of March. The move for most of the population in these regions to work from home even saw demand for consumer electronics rise during the month. However, this has swiftly fallen as millions of people were furloughed.

Jobless claims have risen dramatically in recent weeks. In the US, over 11 million people claimed unemployment benefits over a two-week period. Tin-containing items, such as consumer electronics, white goods, and cars, will now be luxury goods. Consumers will instead focus on more immediate needs, and this view will not change immediately after lockdown ends.

As such, we estimate that the trough in tin demand has not yet reached a bottom. While China may be beginning to recover, the rest of the world is just beginning to feel the economic impact of COVID-19. Year-on-year growth will likely not resume until the final quarter of 2020. Overall, we see tin consumption falling some 8% in 2020.

As a result of the falling demand and slowing production, the balance of the market will also dramatically shift this year. After several consecutive years of deficits, the tin market will

shift into surplus, the largest since the financial crisis.

Long-term fundamentals remain strong

While 2020 will be a mark on tin’s record, the future remains positive. Demand for electronics has been growing rapidly over the last decade, but miniaturisation has been holding back demand for tin in solder. However, the impact of this appears to be nearing an end. Once this occurs, solder demand should trend with growth in electronics, which has historically been at around 10% annually.

Combined with positive forecasts for tin in energy generation and storage, as well as automation, robotics and 5G, there is still reason to be positive on future tin demand, despite the current conditions.