The worldwide adoption of lithium-ion batteries (LIBs), particularly within portable power applications and electric vehicles (EVs), is generating two major concerns.

The first is environmental worry, given that only around only 2–3% of LIBs are collected and sent offshore for recycling in Australia, according to Australia’s Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO). This is also reflected throughout the rest of the world, with a mere 5% of LIBs being recycled globally.

The second is a looming lithium and battery metals deficit. S&P has forecast that even if all lithium projects expected to be online by 2030 are perfectly executed, there will still be a 220,000Mt deficit by that year.

For both reasons, some people are raising urgent and drastic calls for a more circular battery economy.

These concerns have been the catalyst for several companies coming to the realization that the substantial quantity of discarded batteries each year denotes a potentially major resource. The result of this awakening means battery recycling has now started edging nearer to the epicentre of the green energy transition. The unprecedented magnitude of LIB consumption also means that without this circular battery economy, current supply chains will further struggle to cope with demand.

The complete transition to an electrified global fleet will require 10 trillion terawatt hours (TWh)of battery production in the next decade, according to Vineet Mehta, director of battery technology and system architecture at Tesla.

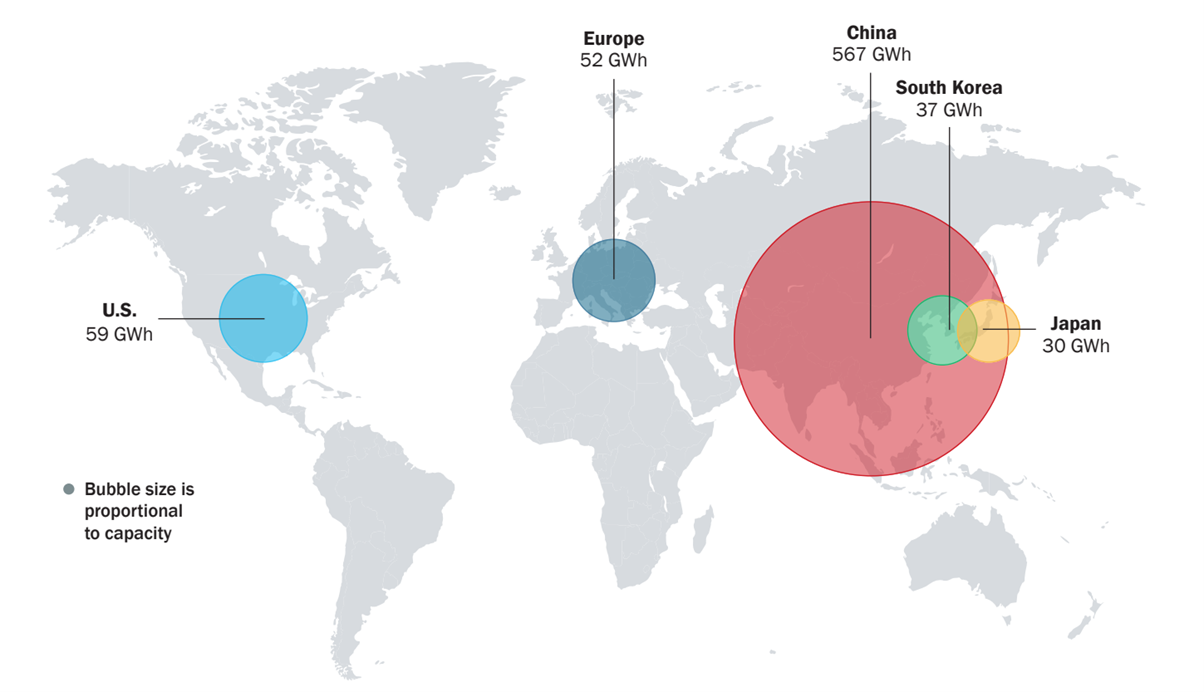

Furthermore, the report states that if the entire planet totally shifted from fossil fuel consumption, including primary energy utilization, the demand would raise close to 350TWh per year. As shown by the visual below, current global cell manufacturing capacities are nowhere near to rivalling those requirements.

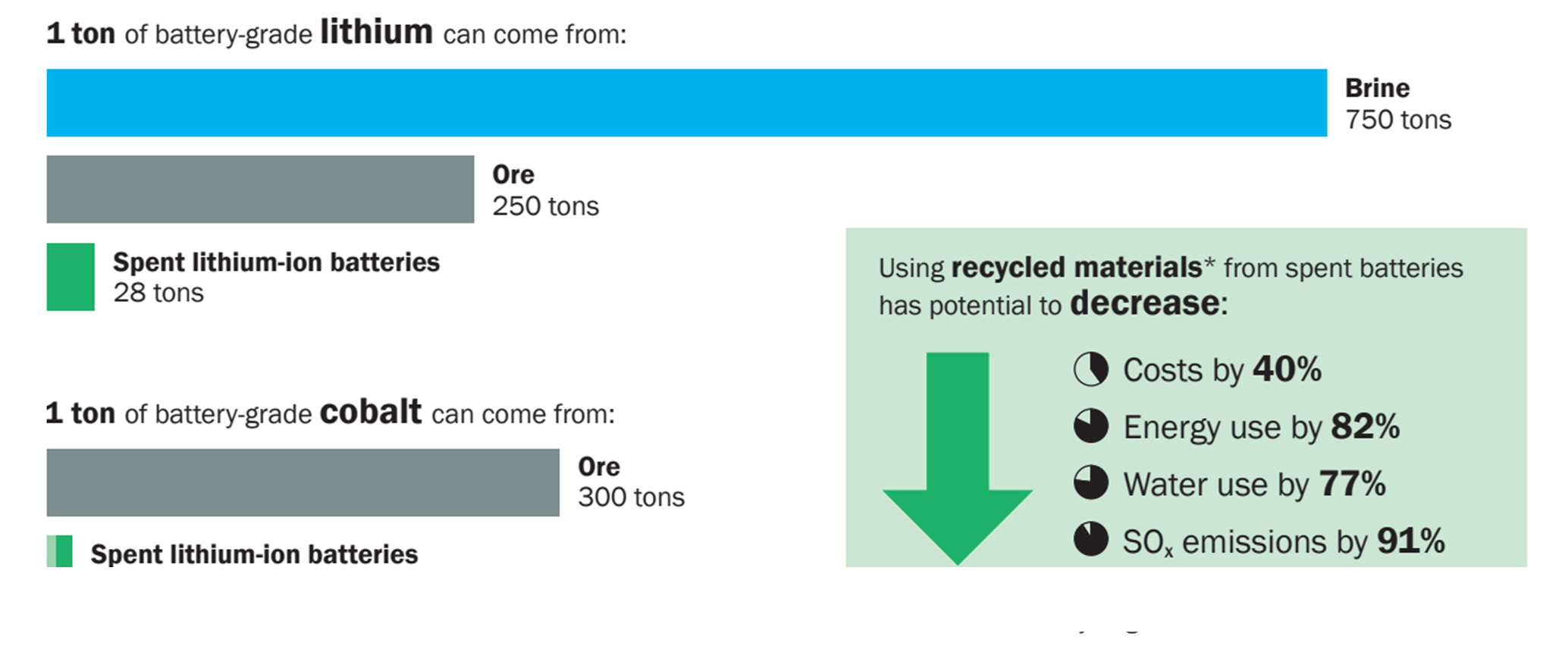

Statistics like this, alongside strained production rates, confirms that battery recycling will need to be drastically increased, and quickly. Companies such as Lithium Australia (ASX: LIT) are responding to this by innovating a technique which utilizes a hydrometallurgical method to process spent LIBs. The company states that not only does this technique efficiently recover nickel, copper, cobalt, and manganese, but most importantly lithium, which the more commonly used pyrometallurgical processing technique, does not.

Even major players such as Glencore (LSE: GLEN) are signing deals with innovative start-ups such as Li-Cycle Holdings (NYSE: LICY), a Toronto-based company focused on recovering critical minerals from LIBs and reintroducing them back into the supply chain.

Alternatively, companies like Ganfeng Lithium (SZSE: 002460), one of China’s leading lithium compounds producers, has gone so far as to develop an upstream and downstream lithium ecosystem, where a comprehensive recycling and processing capacity of 70,000t of retired lithium-ion batteries and metal waste has been formed by the company. Ganfeng said in its 2021 Sustainability Reportthat the comprehensive recovery rate of lithium exceeds 90%, and the recovery rate of nickel and cobalt metal exceeds 95%.

While battery recycling might not solve the battery metals deficit, it could assist companies and the environment by having the potential to source second-hand battery metals. It could also decrease a multitude of other negatively impacting practices, such as excessive water and energy use and sulphur oxide emissions, meaning battery-recycling may well be a well-rounded and helpful way to contribute to the green energy transition.