Last October, I visited the Lapland region of northern Finland to attend the 12th Biennial Fennoscandian Exploration and Mining (FEM2019) conference and a site visit to Agnico Eagle’s (AEM.T, AEM.NYSE) Kittilä underground gold mine.

I also conducted a short course on Capital Markets for Geologists with a few geo-colleagues, moderated a pair of panels, and met with several companies engaged in grassroots exploration in the Nordic nation.

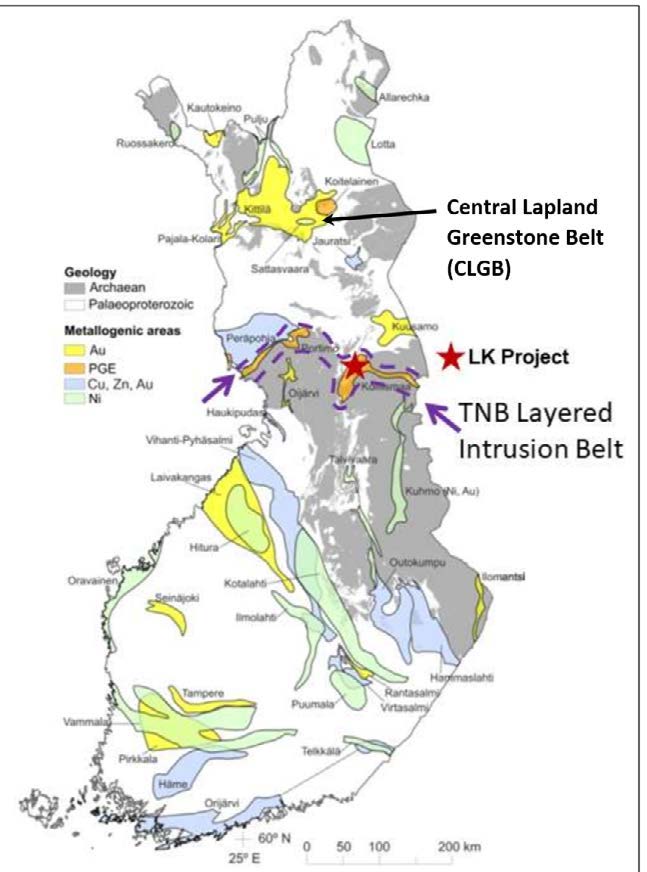

These companies are predominantly exploring for gold in the Central Lapland Greenstone Belt (CLGB), while others are looking for nickel-copper-platinum group metals (PGMs) in the east-west trending Tornio-Näränkävaara Belt (TNB) that extends across Finland and into Russia, (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Regional geological map of Finland illustrating metallogenic domains for gold, PGMs, copper, zinc, and nickel highlighting the Central Lapland Gold Belt and the Tornio-Näränkävaara Belt [TNB], Source: Technical Report for the Kaukua Deposit, Läntinen Koillismaa Project, Finland, September 2019

Figure 1: Regional geological map of Finland illustrating metallogenic domains for gold, PGMs, copper, zinc, and nickel highlighting the Central Lapland Gold Belt and the Tornio-Näränkävaara Belt [TNB], Source: Technical Report for the Kaukua Deposit, Läntinen Koillismaa Project, Finland, September 2019

In addition to its high mineral prospectivity, the Santa Claus Village, saunas, ice-water dipping, and the best pork fried rice I have eaten in my life, Finland boasts the following advantages for junior grassroots explorers:

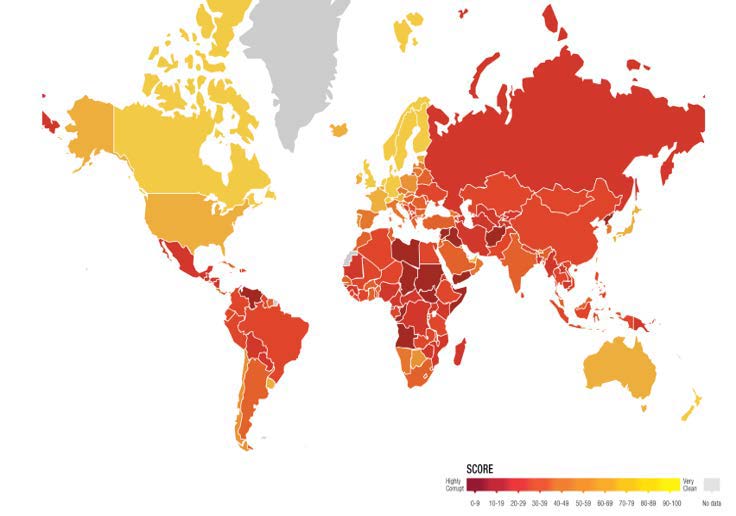

Stable jurisdiction ― It consistently ranks within the upper quartile for various metrics, including the Fraser Institute’s Investment Attractiveness Index (IAI), Policy Potential Index (PPI), and Transparency.org’s corruption perception index (CPI, Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Corruption Perception Index map where the higher the score [yellow], the least corrupt the country is, Source: Transparency.org

Infrastructure ― The country has an extensive network of power lines, airports, and roads, which allows for relatively inexpensive exploration as I did not observe any helicopter supported programs.

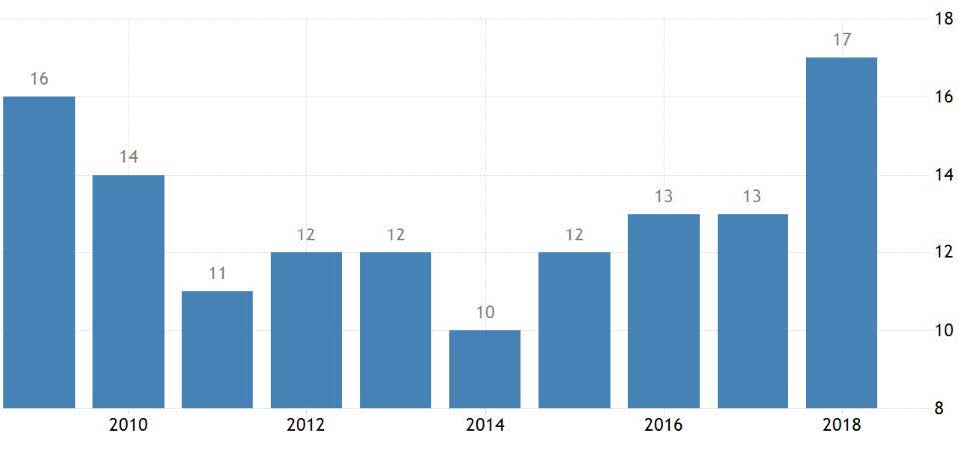

Although Finland’s rank in the World Bank’s annual Ease of Doing Business (EODB) Index has deteriorated somewhat (from 10 to 17 of 190 countries, Fig. 3), it still is among the world’s best jurisdiction and falls just above Australia.

Figure 3: Finland’s rank in the annual Ease of Doing Business Survey out of 190 companies surveyed, Source: World Bank and TradingEconomics.com

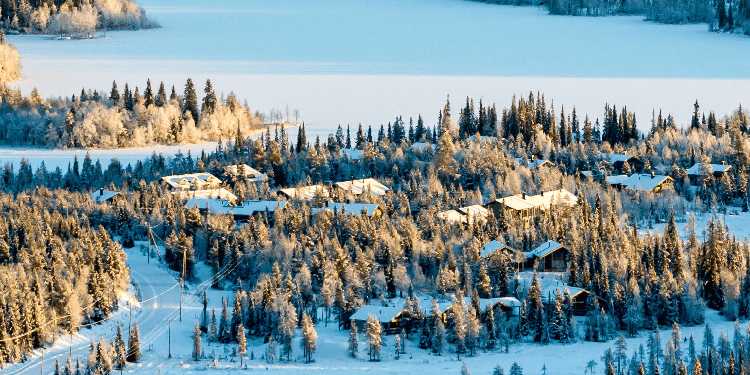

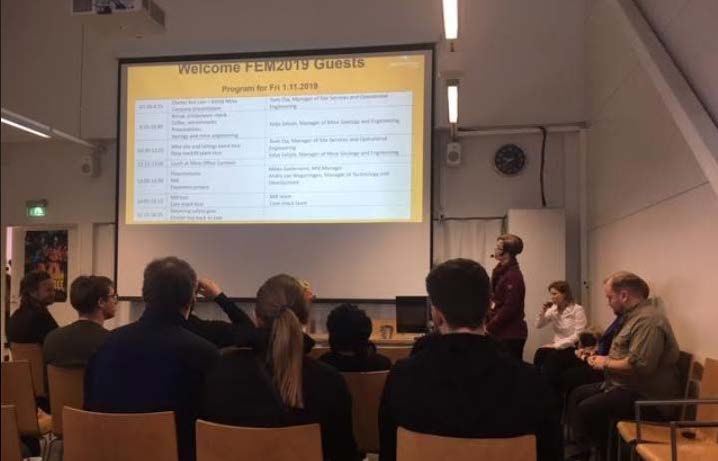

Human resources ― The educational system in Finland is globally recognized as superior, generating a reliable human resource. The average participant at the short course we conducted in Levi, Finland, (Fig. 4), was sent by major precious and base metal companies such as Agnico Eagle Mines (AEM.T, AEM.NYSE), Boliden AB (BOL.SX), Lundin Mining (LUN.T), Newmont Goldcorp (NEM). However, in my opinion, the socialist nature of the population does tend to hinder the entrepreneurial spirit necessary for mineral exploration. This may be the reason for the lack of locally-based exploration companies and the fact that about half of the exploration expenditures are sourced from Canada. However, in my opinion, the socialist nature of the population does tend to hinder the entrepreneurial spirit necessary for mineral exploration. This may be the reason for the lack of locally-based exploration companies and the fact that about half of the exploration expenditures are sourced from Canada.

Figure 4: A group of wide-eyed socialists being exposed to capitalism, Source: Exploration Insights

Figure 4: A group of wide-eyed socialists being exposed to capitalism, Source: Exploration Insights

Government support ― That said, the Geological Survey of Finland (GTK), which has over 400 employees, offers companies electronic databases of government-collected geological, geochemical, and geophysical (magnetic and gravity) regional surveys. Such proactive effort helps support junior grassroots explorers with limited budgets.

The current focus of the organization is on battery metals, recycling, water management, and the improvement of data products for companies exploring in Finland.

Permitting and exploring ― Once a company is granted an all-encompassing exploration license, it’s free to start any work immediately, including mapping, sampling, trenching, or drilling.

While the negatives include:

Land-holding costs ― Land-holding costs are relatively high, starting at around €20 per hectare in the first few years and rising to €50 after a decade.

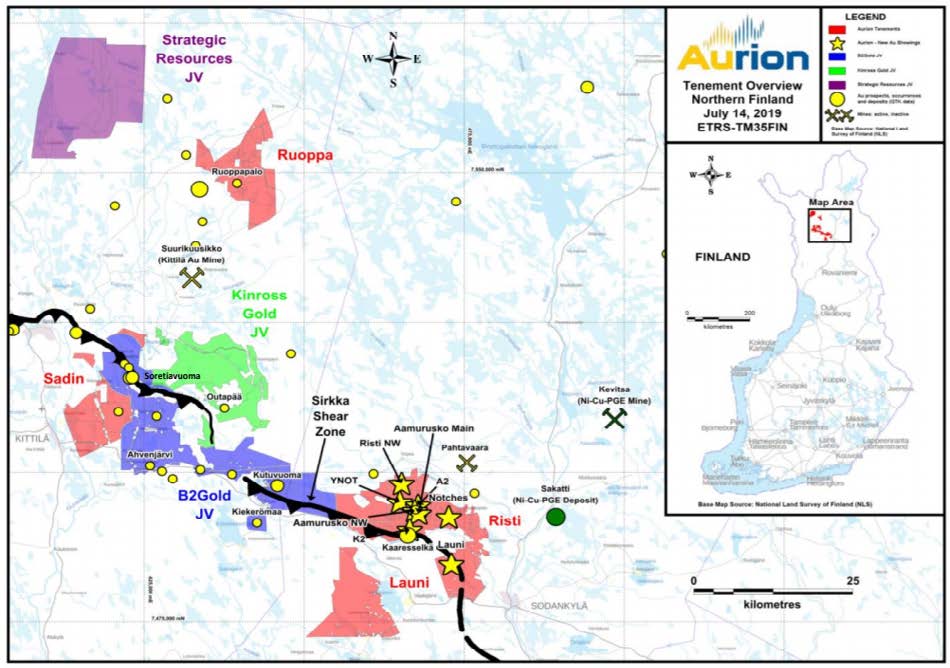

For example, Aurion Resources (AU.V), which controls one of the largest land packages (~100,000 ha) in the CLGB, most of which covers the northwest-trending Sirkka Shear Zone, (Fig. 5), should have annual holding costs of about €2.0 million (C$2.9 M). No doubt, it must mitigate them via its joint venture partnerships with Kinross Gold (K.T, KG.NYSE), B2Gold (BTO.T, BTG.NYSE), and Strategic Resources (SR.V).

The rationale behind the high cost of holding land is to prevent companies from holding on to land for long periods without advancing the project. A non-cash flowing junior may find the costs prohibitive, in which case, forming joint ventures may be the best solution.

Figure 5: Tenements held by Aurion Resources [AU.V] in the CLGB, Source: Aurion Resources

Figure 5: Tenements held by Aurion Resources [AU.V] in the CLGB, Source: Aurion Resources

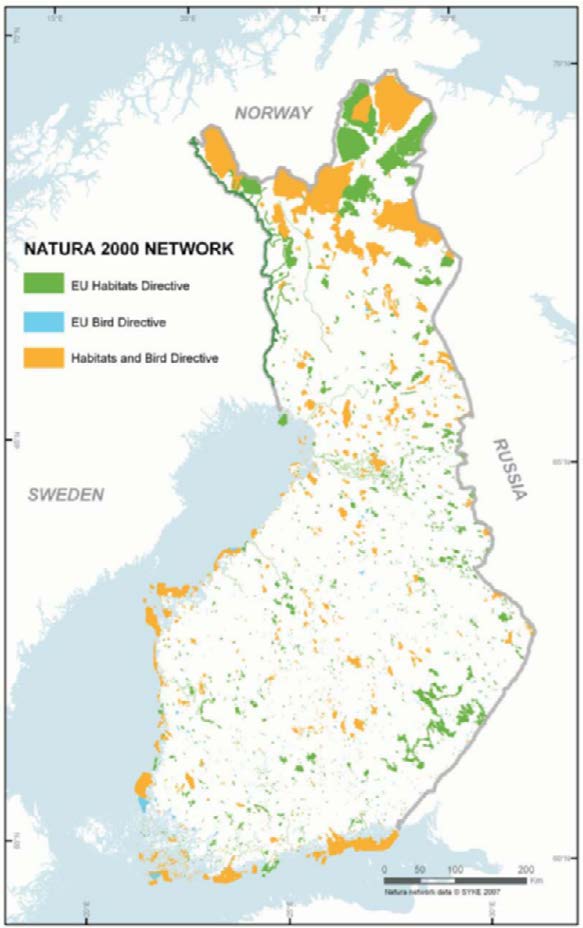

Access to land ― Access to the prospective ground can be hindered by the EU’s network of nature protection areas (Natura 2000) and the occasional local opposition group, (Fig. 6).

Figure 6: Natural conservation network in Finland including those directed by habitats and birds by the European Union [EU] and locally, Source: Ministry of Trade and Industry, 2007

Figure 6: Natural conservation network in Finland including those directed by habitats and birds by the European Union [EU] and locally, Source: Ministry of Trade and Industry, 2007

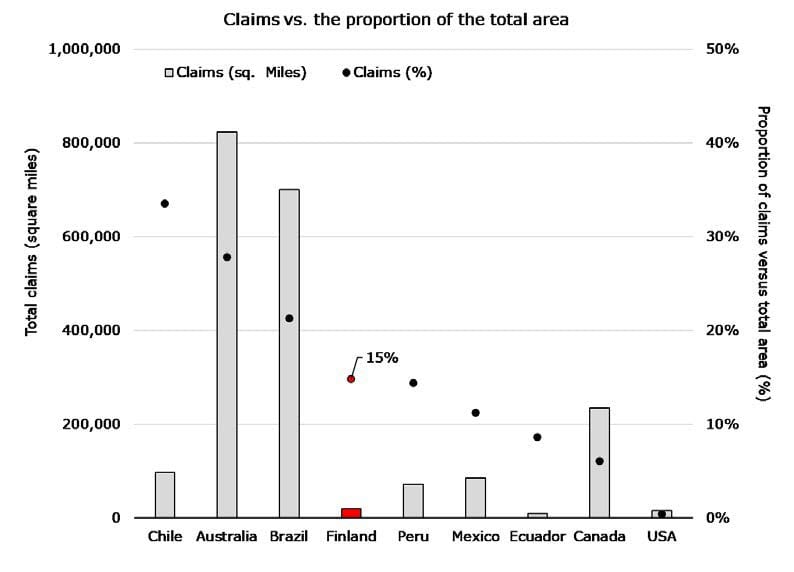

Although the total land area occupied by claims (~19,200 sq mi) is not significant, it represents 15% of Finland’s total area, (Fig. 7), which is comparable to Peru and far exceeds the proportion staked in the U.S for mining and exploration.

Figure 7: Number of claims staked in several leading mining countries, including Finland, and their proportion of the total land masses. Source: S&P Global Market Intelligence and Exploration Insights

Figure 7: Number of claims staked in several leading mining countries, including Finland, and their proportion of the total land masses. Source: S&P Global Market Intelligence and Exploration Insights

Exploration trends

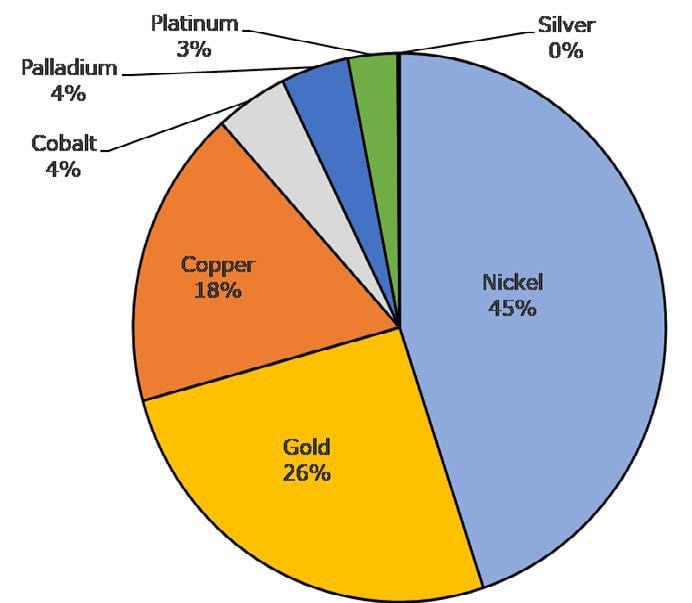

During 2018, Finland’s primary revenue drivers from the metals sector included nickel, gold, and copper, (Fig. 8), while the metals with the most significant impact on global production were nickel (1.77%), cobalt (1.44%), and platinum (0.84%).

Figure 8: Finland’s 2018 metal production revenue employing spot prices. Source: S&P Global Market Intelligence and Exploration Insights

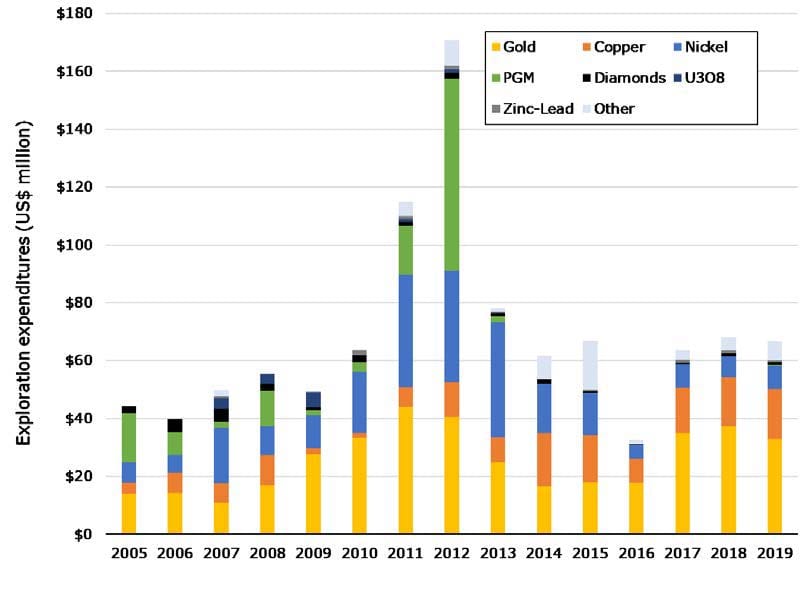

Annual exploration expenditures reached a peak of US$170 million in 2012 and were directed primarily to PGMs (39%), gold (24%), nickel (23%), and, less so, copper (7%), (Fig. 9). Expenditures on PGMs have all but disappeared since then and have also fallen for nickel, but remained increased somewhat in the case of gold and copper. After falling ~60% to below US$40 million in 2016, total expenditures have stabilized at above US$60 million for the past three years.

Figure 9: Annual exploration expenditures [US$ M] by commodity since 2005. Source: S&P Global Market Intelligence and Exploration Insights

Figure 9: Annual exploration expenditures [US$ M] by commodity since 2005. Source: S&P Global Market Intelligence and Exploration Insights

But given the resurgence of both palladium (+48%) and nickel (+59%) prices year-to-date, there may be room for improvement. For example, this weekend, Independence Gold (IGO.ASX) announced an all-share bid valued at A$312 million for Panoramic Resources (PAN.ASX) for its Savannah nickel project in Western Australia.

Also, one of the participants in a panel that I moderated titled Nordic Financing was the CEO of a local private company with an advanced hard-rock lithium asset, that up to now has been funded by groups in Scandinavia. Therefore, money from the region to support mining is not an issue, the problem seems to be the stage of development and the metal focus. Advanced projects and any metals that support a ‘carbon-free’ future such as lithium, cobalt, nickel, and copper are favored over the rest.

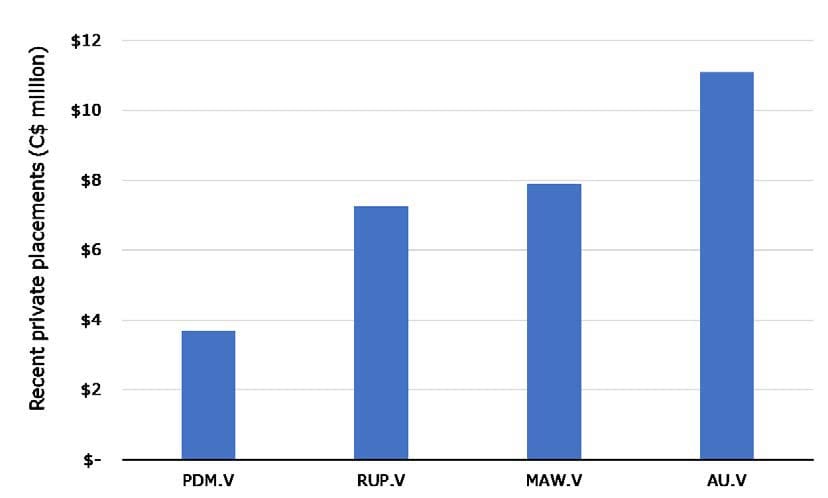

On the other hand, several Canadian-listed junior mining companies recently raised ~C$30 million to explore for gold and palladium in the country, (Fig. 10), indicating that North Americans have no problem funding precious metal exploration in Finland. Also, see my analysis on Palladium One Mining (PDM.V) at the end of this Rant.

Figure 10: Recent private placements by Canadian-listed exploration junior companies operating in Finland, Source: Company press release and Exploration Insights

Local heroes – Kittilä and Sakatti

In addition to prospectivity and other significant advantages, including infrastructure and human capital, among other things, investors in a new jurisdiction like to see examples of success stories.

During the conference, I learned about two notable ones for Finland: the expansion of an existing underground gold mine (Kittilä) and the discovery of a new polymetallic deposit (Sakatti Cu-Ni-Co), both of which support current and future exploration programs.

I had the opportunity to visit Kittilä, also known as Suurikuusikko, which is operated by Agnico Eagle and is the largest gold producer in Europe, with reserves of 4.4 million ounces grading ~4.5 grams per tonne, (Fig. 11).

In 2005, Agnico-Eagle made an offer to purchase Riddarhyttan Resources AB, the previous owner of the Suurikuusikko gold deposit, for US$150 million in an all-share transaction. As the asset covers a greenstone belt similar to Agnico’s land package in the Abitibi region of Quebec, it was of interest to the Canadian-based gold producer.

Figure 11: Kittilä mine tour. Source: Exploration Insights

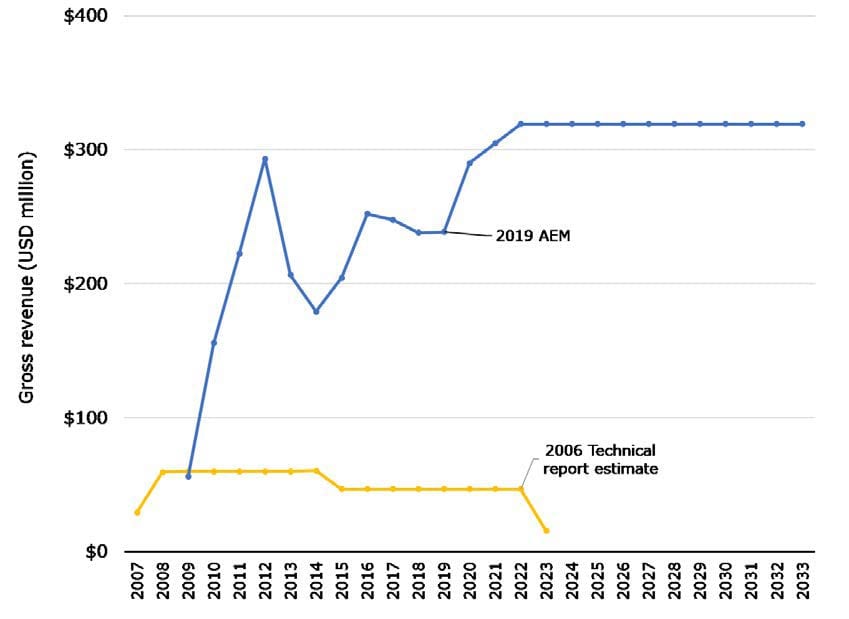

Figure 12: Gross revenue over Kittilä’s life of mine according to the 2006 economic assessment [yellow] versus actual levels from 2009 to 2018 [blue], including a forecast to 2023 at spot prices. Source: Agnico-Eagle’s March 2006 technical report on the Suurikuusikko Gold Project, Agnico-Eagle’s 2019 report, and Exploration Insights

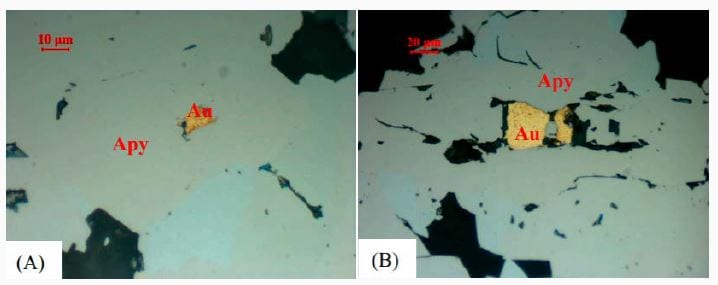

Since the acquisition, the company has grown the resource by more than 185%, which, combined with a much higher gold price, generated a significant increase in the life-of-mine revenue stream from the operation. Despite the successful growth of the asset, the underground grade (4.5 g/t Au) is not exceptional, and since the gold mineralization is refractory (87-88% recovery), it requires pre-oxidation to extract the gold, which is encapsulated by sulfides, such as arsenopyrite, (Fig. 13). The addition of the pre-oxidation circuit (autoclave) would negatively impact both the operating and capital costs versus a free-milling operation.

Figure 13: Example of refractory gold mineralization where fine gold grains are enveloped by arsenopyrite crystals. Source: Mineralogy and Pretreatment of a Refractory Gold Deposit in Zambia, Wang et al., 2019

Regardless, Agnico-Eagle’s decision to expand the operation to 2.0 million tonnes per year by constructing a 1.0-kilometer shaft and modifying the processing plant suggests the company is keen on it.

The rationale behind this move may be to take advantage of the existing plant and the inexpensive power to run it and the project’s ease of access, despite being proximal to the Arctic Circle. The current high-gold-price environment also helps offset the negative impacts of the unexceptional grade of refractory gold ore, (Fig. 14).

Figure 14: Overview of the expansion of Kittilä gold mine, Source: Agnico Eagle Mines and Exploration Insights

At the conference, I also met, by chance, the project manager of the pre-feasibility-stage Sakatti polymetallic (copper-nickel-PGEs-gold) project, a discovery by Anglo American Plc. (AAL.LSE) of which I was unaware, (Fig. 15).

Figure 15: Location of the Sakatti polymetallic deposit. Source: Anglo American, 2013

The major diversified miner began exploring for nickel-copper sulfide deposits in Scandinavia in 2004 and discovered the Sakatti deposit in 2009, thanks in part, it says, to the geological and geophysical data provided by the Finnish geological survey. The deposit was actually Target #8 of its priorities, which supports the need for perseverance in exploration.

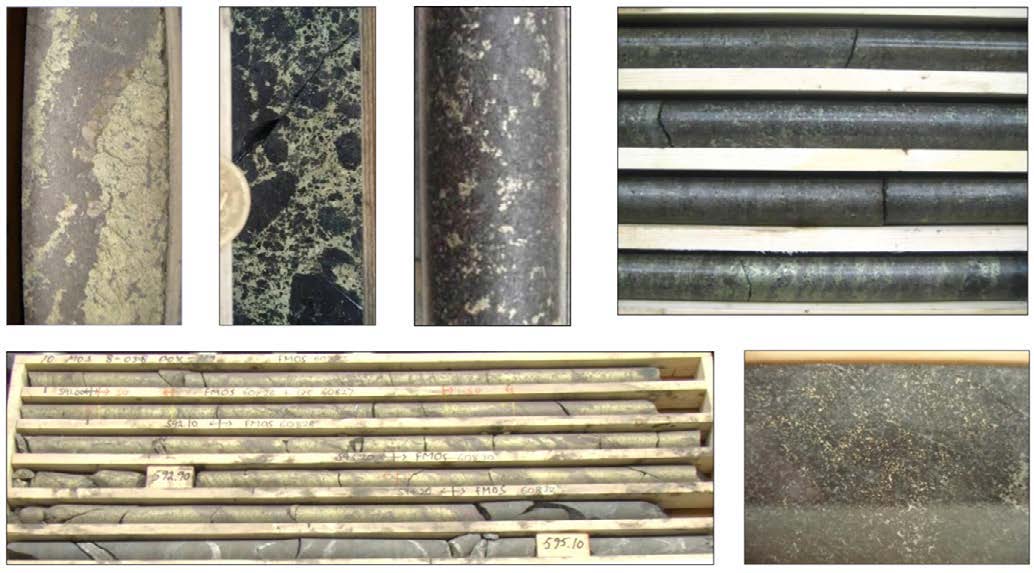

The nickel-copper-PGMs mineralization ranges from massive to semi-massive to disseminated and extends to depths of 700 meters, (Fig. 16). Some reported diamond (core) drilling results include intersections of 48 meters grading 3.1% copper, 0.47% nickel, 0.30 grams per tonne PGEs, and 0.47 grams per tonne gold. The current resource hosts over 40 million tonnes grading over 5% copper equivalent, which is impressive.

Figure 16: Massive, semi-massive, and disseminated copper-nickel mineralization with PGEs and gold. Source: Anglo American, 2013

Seen at FEM2019

While at the FEM2019 conference, I caught up with several junior miners, predominantly Canada-based, through presentations and/or meetings, (Table 1). Non-cash flowing juniors will provide about a third of the US$60-70 million budgeted for exploration in the country in 2019, with the biggest slice being directed to gold.

Aurion Resources (AU.V) and Firefox Gold (for full profile, please see here) are both grassroots explorers and hold the largest land packages (>100,000 ha) in Finland, predominantly on the CLGB. Mawson Resources, who arrived in the country in 2009, appears to be the company with the longest history in the Nordic nation.

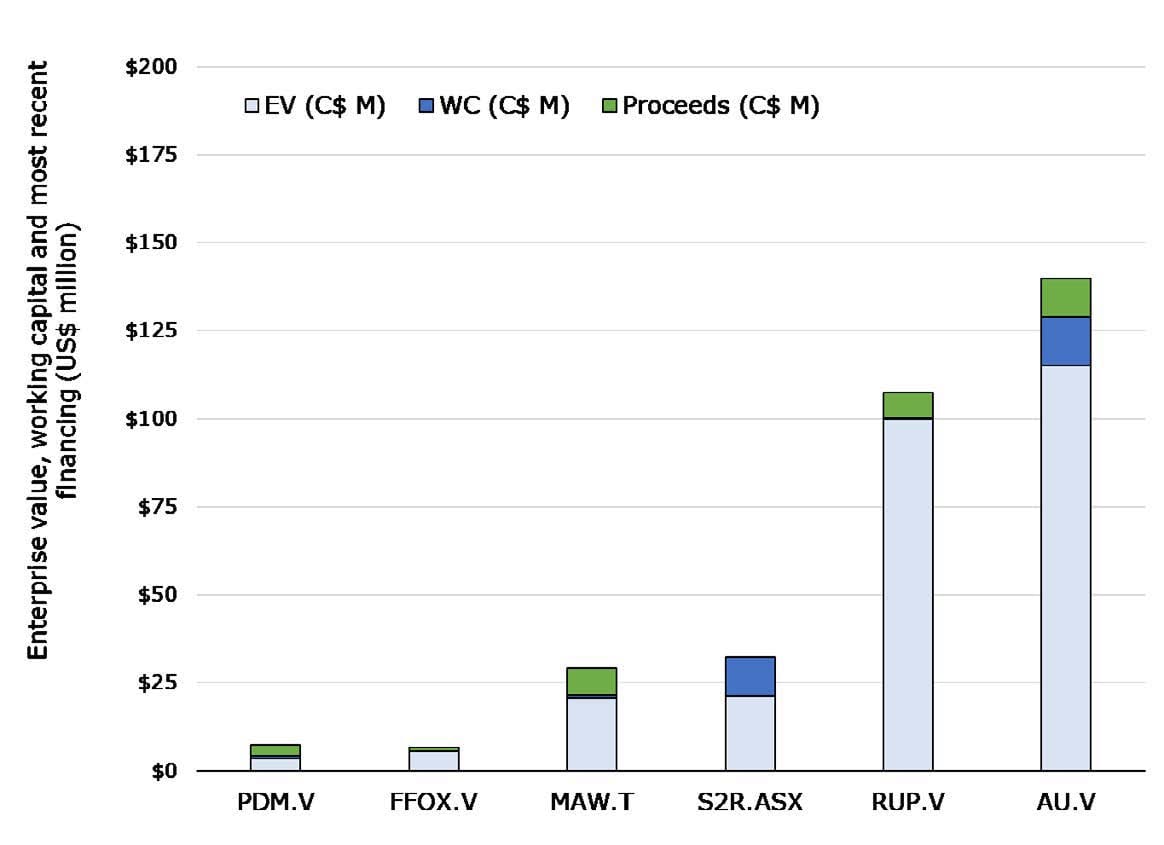

The average enterprise value of the group is C$45 million but ranges from a low of ~C$3 million for Palladium One Mining (PDM.V) to C$115 million for Aurion, (Fig. 17).

Figure 17: Enterprise value [=market capitalization – working capital], working capital, and most recent gross proceeds from private placements, after last reported financials. Source: Company financials and Exploration Insights

The average of the last reported working capital positions was C$4.4 million, but, again, the range was wide, from C$0.1 million for Rupert Resources (RUP.V) to C$13-$14 million for Aurion.

Five of the six explorers have executed private placements since the end of June for a total of ~C$30 million, (Fig. 10), with Aurion attracting one-third of the gross proceeds (C$11 M).

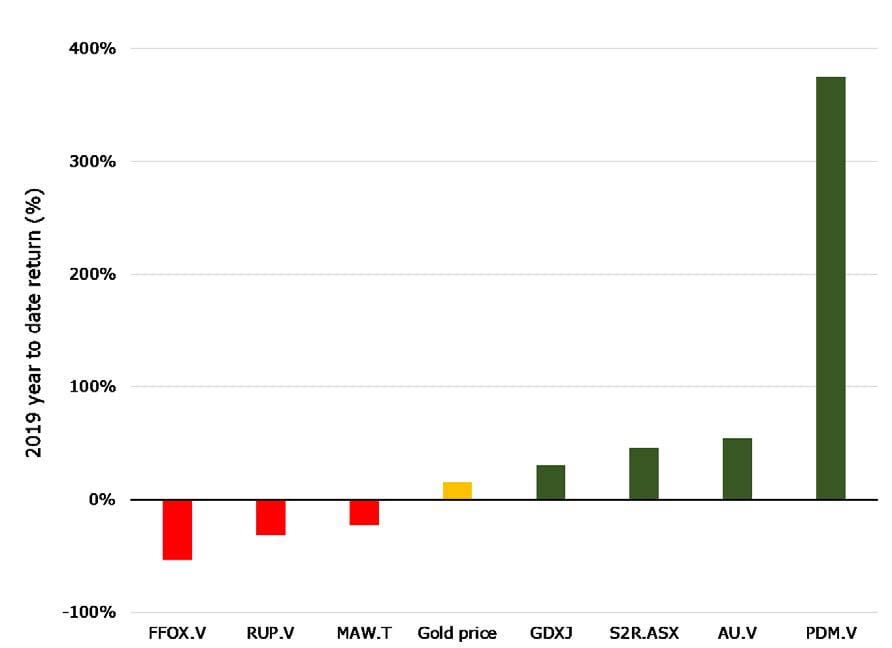

Half of the companies generated positive returns in 2019 year-to-date (46% to 375%) while the other half underperformed the market and the gold price (-23% to -53%, Fig. 18).

Figure 18: Year-to-date returns for a peer group of junior explorers operating in Finland compared to the GDXJ [gold ETF] and the gold price. Source: Investing.com and Exploration Insights

For companies seeking to add precious and base metal assets in low geopolitical risk jurisdictions to their portfolio, Finland presents a good opportunity. The infrastructure challenges for many countries north of the Arctic Circle, such as Canada, have not been an issue for Agnico Eagle at Kittila allowing for moderate underground grade refractory ore to be extracted at a profit. For explorers, the underexplored potential under a thin layer of glacial till will have to be weighed against the costs of land holdings and problematic districts.