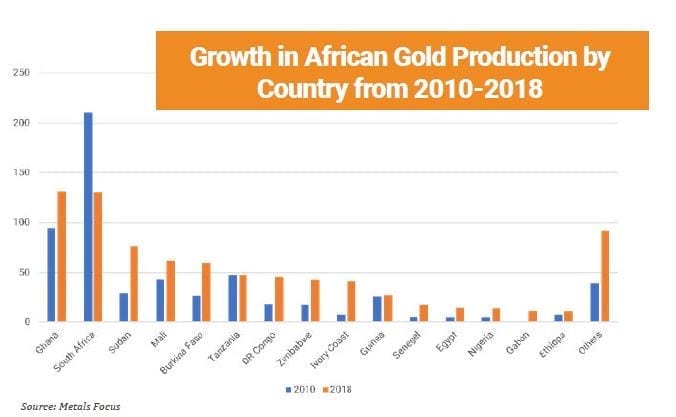

As a long serving international precious metal merchant and financier, Auramet maintains relationships with gold mines located in key African countries. Our investments have ballooned in the past five years as gold production growth on the continent has outpaced any other region in the world. Although South Africa’s production continues to spiral downward, growth in West Africa has been explosive. Ghana, Mali, and Burkina Faso together produced nearly twice what South Africa did in 2018 with Ghana edging South Africa from its long-held leading position as the number one gold producer on the continent. Recognizing this growth spurt, we have provided loans to support mines in these four countries as well as Tanzania, Cote d’Ivorie, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Senegal, while accelerating the expansion of our offtaking presence (Auramet purchased more than 7 million ounces of gold in 2018). We continually seek new opportunities in the region and have grown our African book from 10% of our total to about 20-25% over the past 3 years. Our industry risk assessment in this dynamic region is the focus of this article.

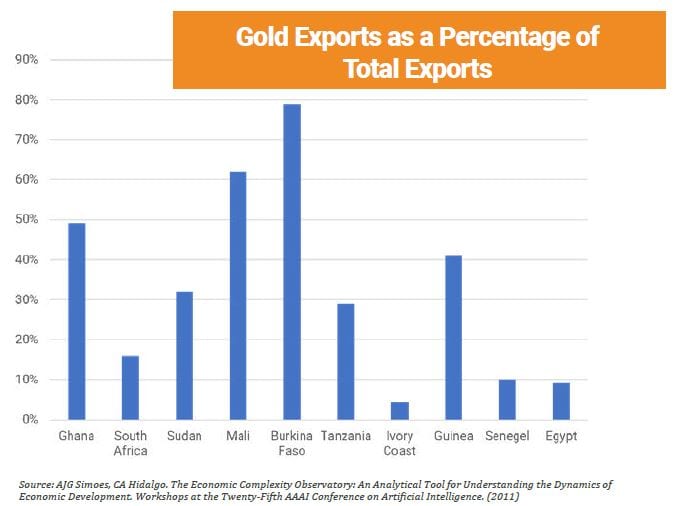

Gold mining in Africa, undertaken today by at least 34 countries on the continent, represents a significant share of Africa’s export revenues. Given that the continent holds 40% of the world’s gold reserves, this trend will likely continue. And as anyone who has financed natural resources in the emerging markets has learned in the past, the greater the importance that a specific commodity has in bringing foreign currency into an exporting country – all other things being equal – the less risk one has in financing it. We bear this in mind when developing our overall investment strategy and going through our risk analysis.

When allocating capital to a project in Africa, Auramet applies the same discipline that it does when investing in other regions: we consider the projected rate of return and then determine if the investment fits within our risk parameters and is consistent with our portfolio goals. No matter where we invest, we pay attention to political risks.

Political Risks

It has not gone unnoticed in our industry that certain countries in Africa – particularly West Africa – have gradually become among the lowest-cost gold producing nations in the world. While this far from guarantees a project’s success, a low-cost mine can provide a welcome cushion when modeling mine underperformance or weakening gold prices into any sensitivity analysis. But even in a region of low-cost production, there is no shortage of potential problems to avoid and Africa poses unique country by country political risks.

Working in developing and emerging nations presents distinctive challenges; understanding local culture, laws and politics to name a few. These problems put a premium on choosing the right partners to work with. Therefore, before undertaking any due diligence with regards to political risk, Auramet would have already considered our relationship with the owners/operators of any specific mine. This point cannot be overstated. Since Auramet opened its doors 15 years ago, the foundation of its entire trading and investment business has been built on relationships that have been established over the years with various producing companies, miners, refiners, and end-users. As we expanded and began to entertain more risk in the global mining space, we carried this fundamental philosophy forward. Knowing our partners gives us a base of comfort as we dig deeper into the challenges and risks of financing any specific project – including those located in areas of political instability.

Given that most gold mines in Africa are majority-owned by foreign multinational companies, the possibility is ever-present that any given project will be subjected to increased value added taxes, increased royalties, special taxes on excess profits, ownership percentage restrictions, unfavorable changes to the mining codes or any combination of these. Resource nationalism is a real and understandable phenomenon, particularly in areas of high poverty. There are few ways to accurately predict or adequately mitigate the risks of a government unilaterally changing the economics of a given project, but we do our best to assess these risks along with more conventional political risks (government instability, civil unrest, electoral difficulties, etc.)

To understand the political risk related to any project, you first need a base understanding of the history and current political climate of the country and region in question. Then you can look at the characteristics of each mine to see how it might be impacted. Where exactly within the country is the project located? What percentage of its management is local? What ties exist between the mine and various government and financial related entities (e.g. local banks, African Finance Corporation, African Development Bank, IBRD, etc.)? The answers to these questions can provide valuable guidance when calculating the overall risk. Obviously, a geographical location isolated from past, current, or future unrest reduces the risk of sabotage or related problems; managers taken from within the local community will more likely bring about improvements to a mine’s critical relationship with the host community or government; and strong ties to local, regional, or international development organizations enhance the likelihood that concession deals made between a government and a mining company will be fair and will continue to be honored. Simple things like the timing and nature or competitiveness of general elections can play an important role in determining the tenor of a loan transaction.

Assuming we get comfortable with political risks, our decision making process is conventional: We look closely at management and weigh its experience against the current challenges it faces; we drill down into the balance sheet to make sure that debt levels are supported by the base business case and any possible deviations from it; we consider the legal environment to determine what financial structures make sense; and we consider the mine itself and the infrastructure surrounding it to get comfortable that not only will metal be recovered in a responsible manner, but that there is a clear path from the mine to the gold refinery. Much time is spent on this latter group of risks as it requires a keen analysis of all aspects of infrastructure including the roads, maintenance buildings, power, water supplies, waste sites, pumps, and piping required to operate a modern mine. Once we consolidate all these risks and weigh them together, we examine how the investment fits with our overall strategy and portfolio and make decision.

Two recent Auramet investments illustrate our overall approach within the specific countries below:

Twangiza and Namoya Mines in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (“DRC”)

These two mines are operated by Toronto based Banro Corporation, a company with whom Auramet has a long relationship. In2011, Twangiza became the first commercial gold mine established in the DRC in over 50 years (commercial production began in September 2012). Namoya, similarly sized, started producing in 2016.

Auramet began making small short-dated prepayments for Twangiza doré production bound for South Africa for refining in 2015. At that time, it had been nearly eight years since the government famously negotiated or cancelled all the mining contracts that were in place, and there was relative stability in the sector. Additionally, the M23 armed group that had been undertaking violence in the eastern region of the DRC (where the mines were located) had been defeated in late 2013, ushering in a period of optimism. Although the country still has armed groups (civil defense militias, rebel forces, or conventional criminal gangs) the government had done a decent job minimizing their influence at the Banro mines and we were confident that they would see to it that gold got produced and exported for hard currency.

Auramet continued to successfully support the mines through 2017, with larger and longer dated facilities (some with political risk insurance, some without). But as the DRC general elections scheduled for December 2018 approached, and the outcome was proving increasingly difficult to predict, we reduced our exposure.

Karma Project in Burkina Faso

Operated by True Gold Mining based in Vancouver, the Karma Project was the first undertaken by the company in Burkina Faso when it began construction in 2014 (Endeavour Mining Corporation would later acquire True Gold in April 2016). The property, consisting of several deposits within a ten-mile radius of one another, lies about one hundred miles northwest of the country’s capital. The project ran into early trouble when disgruntled artisanal miners in the area set fire to equipment and machinery in early 2015, after hearing a leader of a local village claim that one of the open pits would damage the local mosque and threaten the safety of the village. The government halted production for four months. Although new management was successful in getting the construction restarted after holding discussions with the village and other local stakeholders, it had trouble raising the money required to finish the job. After a careful review, Auramet stepped up with an eighteen-month, $10 million equipment loan.

Not many lenders would have done this as there were several factors that justified a firm “no thank you,” but we saw an opportunity to establish ourselves in Burkina Faso with a company that we knew well. We are not afraid of work and we did a deep dive on all the issues in order to make a thoroughly informed decision.

It is not always possible or prudent to do all the project due diligence ourselves. We often rely on outside consultants to look at specific issues for us (e.g. environmental or social) or prepare reports on a more general basis. In the case of the Karma Project we did both. From an economic standpoint, the numbers looked good, the technology (heap leach mining) was basic, the anticipated cost of production was in the range that matched our expectations, and the project was on time. Where we needed additional comfort was in the analysis of the social and environmental risks. What we found encouraged us; through engagement with the local community and government, new management had undertaken extensive efforts to address potential problems related to the mines: general resettlement issues were discussed as well as solutions related to construction timing and completion and labor issues; senior employees with extensive experience in Africa were hired to manage the project; and management went above and beyond the minimum standards of the Equator Principles.

With that work done, political risk was the final thing we had to get our hands around. We were aware that since gold represented a vast majority of the exports of the country, the government would be incented to keep the mines and infrastructure working successfully. On the other hand, we knew about the political problems that plagued the country and could lead to fighting or general unrest. After careful consideration, we took out political risk insurance (building the moderate cost into our structure) and moved forward with our transactions.

Supporting gold mines in Africa is not for everyone. But as an established precious metal merchant with ties across the industry vertically, Auramet can consolidate all the associated risks and assess them with collective knowledge acquired over decades of working within the sector.