When Canada’s former Prime Minister, Pierre Trudeau, was asked why the federal government, rather than provincial governments, oversaw the fishing industry, he replied: “Because fish swim.”

Fish are not distracted by borders or any other lines on a map. Likewise, political boundaries do not stop emissions, nor any other sustainability concept such as equality, innovation, and dare I say it, supply chains.

Yet, in order to manage these challenges that are borne by everyone and no one at the same time, policy is needed. And policymakers have stepped up in a big way, which is why we are embarking on the next commodity cycle – one where technology metals are a key part of the complex.

Commodity cycles emerge out of a changing world order

The last commodity cycle began when China joined the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001. China’s policy – prosperity for the people – effectively kicked off over a decade of commodity demand growth that hadn’t occurred since post-WWII.

Commodity cycles need scale, speed, and investments to materialize. Global copper demand increased by over 5Mt in just 10 years, all from China. If the average copper mine (of significance) produces 100Kt annually, did we really build 50 new copper mines over that decade?

Another product of the last cycle was financial innovation in commodities: trading instruments and interfaces that made the metal markets a ‘mainstream’ alternative asset class. Gold ETFs, iron ore futures, and aluminum premiums were open for trading and arbitrage. Commodities, currencies, and CDS’s could all be discussed in the same breath.

And so emerged Commodity Funds, one of the cleanest ways for investors to gain exposure to commodity cycles. And now, portfolio managers have more markets than ever to take advantage of investors’ growing awareness of ‘new economy’ supply chains. Even carbon credits, an explicitly policy-driven financial instrument, are making their way into more trading portfolios.

Today’s commodity cycle is about sustainability

Sustainability is more than just climate. It includes equality, responsibility, well-being, innovation, and secure supply chains. It is about pivoting the world to one where our consumption generates fewer negative externalities.

It is this policy that drives the current commodity cycle, which will only accelerate as more dollars go into the ground and into hard assets. For every dollar invested in fossil fuels, US$1.7 is spent on clean energy1. Five years ago, this ratio was 1:1.

Interestingly, and putting aside any skepticism one might have on how much emission reduction is actually achievable, we know that heatwaves, or ‘once in a century storms’, are not enough to put real dollars to work. In other words, climate disasters on their own aren’t driving any commodity cycles.

Rather, the better incentive for large firms to invest in climate mitigation are stricter climate standards, i.e., policies such as carbon tax and disclosure requirements2. Moreover, such policy is still more important than the known aftermath, such as climate-related damages costing US taxpayers over US$500B per year since 20163. In other words, some 32% of US GDP growth since then was generated by climate reconstruction efforts.

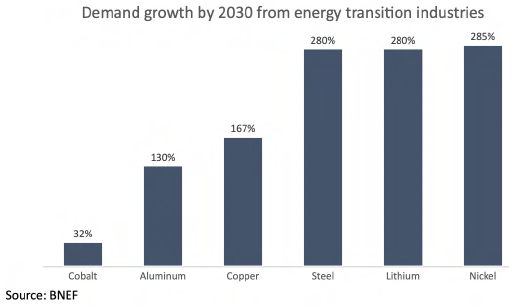

Given that policy appears to have an outsized impact on capital decisions, the investment going into ‘new economy’ industries such as renewable power, electric vehicles, energy storage, carbon capture, carbon offsets, and hydrogen/charging infrastructure will go well beyond simply tracking population or GDP growth. These industries are both adding to, and replacing, existing capacity.

As such, new commodity markets are coming to the fore. Lithium, nickel, cobalt, manganese, tin, graphite, silicon, some rare earths, and their supply chains, are increasingly part of discussions amongst policymakers, and they are making headlines.

We are seeing new pricing benchmarks and even futures curves for emerging niche commodities, creating price transparency for a growing pool of industry players, and giving lenders and investors more visibility, and hedging ability, into what they are financing.

Sustainability comes with a price tag

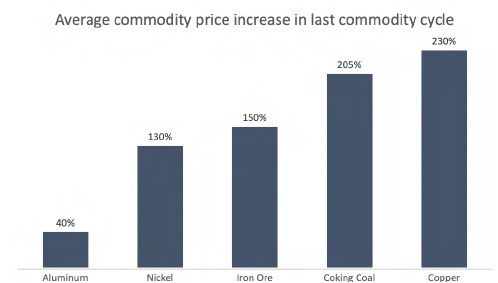

From a commodities perspective, doubling global supply of anything within a decade requires significant capital, and tends to come with higher operating costs as more marginal projects are needed. Thus, commodity cycles compel higher commodity prices.

Even steel prices, which were generally viewed as deflationary as China’s own capacity increased to half of the world’s 1.7Bt of production in less than 10 years, managed to increase by 14% on average.

Metal prices will ‘step up’ again. This cycle, it goes beyond the usual culprits of lower grades and smaller scale projects. Prices will be boosted because they will also better reflect the true cost of doing sustainable business.

We must better produce what we consume

In the current economic environment of sticky inflation and uncomfortably high financing costs, it is easy to claim that elevated costs are transitory. Reality is likely to prove different. Cost-push inflation for commodities is not only going to be volume-driven, but process-driven as well, i.e., building and implementing more sustainable operations and firms.

The mining sector represents 2% of global GDP but contributes to 6% of global emissions. BHP has stated that it expects to spend US$4B to reduce its Scope 1 & 2 emissions by 30% by 20304. While this only represents 5% of BHP’s aggregate capex budget, it also represents 5% more than the company may have had to spend otherwise.

Extrapolating this percentage to broader mining, chemicals and energy industries suggest over US$120B should be budgeted annually for decarbonization efforts alone. This spend will still not get the industry to ‘net zero’.

The other parts of the sustainability equation – equality, responsibility, well-being, innovation, and secure supply chains, also add to structurally higher prices. Taking care of people costs more. Future-proofing a business has a capital outlay but should ultimately generate value.

The reality is that, despite words like ‘critical minerals’ and ‘strategic metals’, the world has always found a way to produce what it wants and needs. But policy, rightfully so, is fast-tracking the build out of a new economy.

Thus, the ingredients for the next commodity cycle, such as scale, speed, and investments, are now coming together to meet our collective sustainability policies and goals. Metal prices, especially for technology metals, will reflect higher standards for production, consumption, and all manners of life on this planet. Fish included.