How are the current global, economic, and geopolitical trends impacting metals supply, demand, and pricing?

I think they are still a negative factor, particularly for metals like platinum and palladium. After Russia’s incursion into Ukraine, the London Bullion Market Association (LBMA) has deemed Russian refineries “LBMA non-good delivery”, meaning they can’t easily make their way into the Western world. I think for various other metals like nickel and gold, it’s increasingly difficult to make investments in a productive capacity in Russia, and that will ultimately limit supply.

Aluminum from RUSAL and others is also a potential issue, not necessarily right now, but I think there’s been a broad chilling effect on the free flow of metals from that part of the world. Looking at the rest of the geopolitical factors, there’s tension between the US, the Western world, and China. So far, I haven’t really seen a huge impact from that. Certainly, some of the semiconductors like germanium, may be a bit out of our purview, but for other metals we haven’t seen a huge impact.

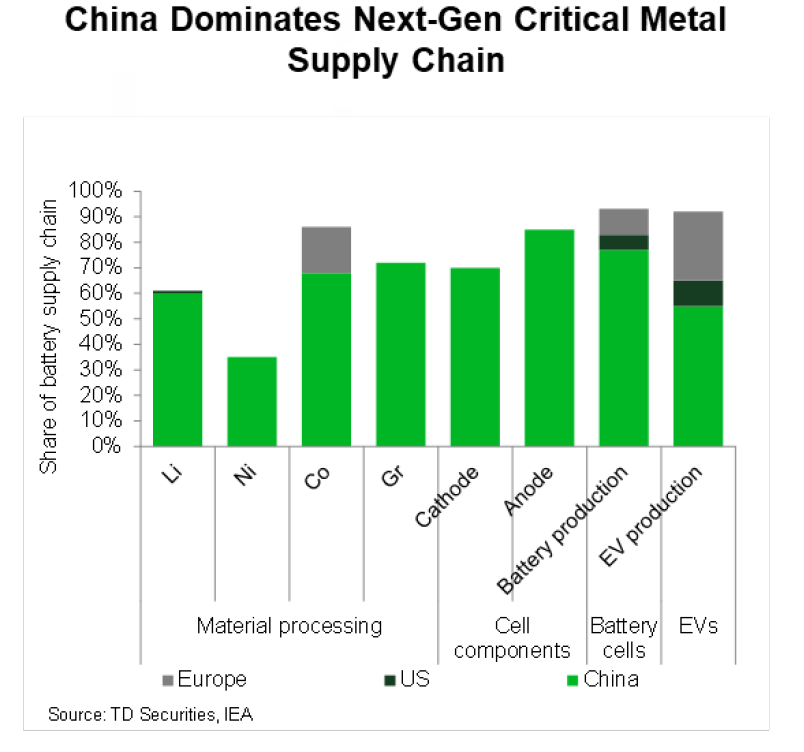

Yet, China has been, and continues to be, a key supplier and processor of critical metals for electric vehicles (EVs). You can envision a situation where if tensions rise to more problematic levels, some of those flows may be limited, and that would have a negative impact on our move towards electrification and a net-zero CO2 environment with the Western economy.

So, I think it is a factor, but I would say in no way a crisis at this point. And I will mention that a lot of the metals that have been sanctioned by the West, as well as oil, the markets tend to find a way. It takes a while to adjust, but maybe the flows will go into more friendly geopolitical environments.

There have been a lot of regional regulations such as the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) in the US. What are the impacts that you’ve seen from these types of regulations on the industry overall? And where are these impacts largely being felt?

I think increasingly the West, specifically the US, is taking very robust action to encourage the transition into carbon free sources of energy and transportation. You’ve just mentioned the US Inflation Reduction Act. That is a massive bill with literally trillions of dollars of potential spending. I’m not sure we fully know how that’s going to work, but we’re already starting to see investment decisions being made that take into consideration potential subsidies for EVs and batteries.

For Canada, we’ve seen billions of dollars being divvied up to auto producers to put their battery manufacturing plants there, hoping that there will be knock-on effects and complimentary industry setting up in Canada. We can certainly see a similar set of circumstances, and in fact, we’re seeing it in the United States where there is a lot of capital, subsidies, and tax breaks being offered.

People will locate their key facilities in the US and in Canada. As time goes by, rich jurisdictions will create environments that will attempt to bring in capital to start those industries in their domiciles. This will benefit their economies so they can have a head start, further develop these technologies, and be the sources of export cells for the rest of the world as that transition takes root globally.

A large part of this discussion is also on the idea of critical minerals, and we’ve seen a ton of focus on these in Canada, Australia, Europe, and the US. How is this theme changing the metals and mining landscape?

For now, my perception is that it has been more of an idea than real action. A lot is being said that could potentially mean a better investment environment and better regulations, but so far, there haven’t been fundamental changes that would precipitate the speedy development of mining facilities in the West.

The narrative is becoming more positive, but we haven’t seen that reflected in actual investment, construction, or removal of regulations. This certainly has been the case in Canada. You can envision a situation in parts of the US where we are talking about critical minerals, but it’s quite another thing to convince local communities to allow mining. And I think those issues need to be resolved.

There needs to be a steadfast regulatory system and a set of laws that once something is approved and goes through the assessment, then we need to remove risk and not have projects delayed because of local disagreements or opposition.

You must be able to negotiate and work with communities, and once it’s been decided, it has to be certain, or these projects are not going to get done.

At this point, the West is very much reliant on China as a source of a vast majority of critical minerals. But there is really no guarantee that over time China will deliver the supply needed. I think it stands to reason that policy in China is going to favour itself rather than the West and that is something that needs to be considered a lot more seriously by policy makers.

Looking at the metals impacted by the energy transition, where is most of the discussion focused right now? We’ve been hearing a lot about Indonesian nickel, but what are some of the biggest movers you’re seeing?

Nickel is something that the world is going to need for the batteries required to power hydrocarbon-free vehicles. But in Indonesia, they are talking about down streaming policies, meaning you might not get as much material from that country as you need. Copper is similar. We’re seeing jurisdictions in South America, such as Chile, discussing limiting ownership and taking fuller control of these assets.

As far as I’m concerned, copper is probably the key metal. I can envision a future technology that would reduce lithium and nickel, and find alternatives such as hydrogen as opposed to batteries. So that’s flexible, but none of us can really predict what technology will come up in the long run.

The one metal that we’ll definitely need and you can’t thrift away from is copper. Copper is a basic conductor and is the metal for electrification. It is used in electrical motors, everything from transformers to switch gear. When we look at long term investment in copper projects, (given the current state of technology) the quantities needed to fulfill these targets set by the Paris Accord and some other national ones, there really isn’t enough copper.

The investment simply isn’t there, there isn’t appetite on the investor side, nor is there appetite in various boards of directors of these large companies. We’re seeing investment, but not in the quantities needed. And there is a bit of a contradiction with the negative relationship between the carbon intensity of projects and investment. The more carbon intensive projects, mining projects, or oil projects, the less investment there is.

That has a lot to do with perceptions of environmental impact. And it doesn’t seem to be a big macro view that while a mining project itself will release CO2 over its lifespan, you need to be able to get the metal out of the ground. Over a 30-year period or so, there are a lot of net benefits.

We’re already starting to see investment decisions being made that take into consideration potential subsidies for EVs and batteries

I think that kind of ESG calculus must be set in when we’re looking at investment rules. We’re going to have to look at the long-term cycle when we decide whether a project is dirty or clean, it might be dirty on the micro level, but if it reduces fuel consumption of diesel or gasoline over the lifespan of the millions of vehicles that will come as a result of these mining projects, that needs to be considered, whether it is actually dirty or not, it has to be the entire cycle, not just the specific project. And I don’t think we’re quite there yet.

Let’s look at trends for metals like gold, which are less involved with the energy transition theme. Gold certainly has an enduring role in the global economy, whether it’s an investment or store of value. Why does it continue to garner so much attention when there is so much focus on the energy transition?

I think a big reason here is we’re more geopolitically unstable than before and gold is an asset that is no one’s liability.

Once you have a bar of gold in your central bank, no one can take it away from you. You have it, it’s yours, it’s got intrinsic value as it has for millennia. You can trade it, swap it, and still have a physical claim.

In a world where we’ve seen as much as half of Russia’s FX reserve sanctioned by the Western world, where they couldn’t use their hundreds of billions of dollars to trade and create economic activity, it seems that gold was a good option because they could physically move it and swap it with others for credit and it was unsanctionable.

You can also envision an environment where China, with US$3.18T worth of FX reserves, may want to de-risk a little and have more gold in its portfolio… At some point, should the situation turn sour. I think it’s just portfolio diversification on the part of central banks.

Another concern is that the value of the US dollar might erode over the long term. Why? Well, the US has massive amounts of debt in the trillions of dollars at this point – above 100% of GDP. And there doesn’t seem to be a lot of indications that this is slowing down.

As the population in the US and the West ages, we’ll have more and more unfunded liabilities and it’s not all that clear where the money comes from. Certainly, there has been an unwillingness to tax people to pay for our expenditures. Ultimately, this means that you’re probably borrowing in the market, and in the long run it could very well mean that interest rates in real terms are low and purchasing power is eroded over time.

We’re seeing it now, where inflation is quite high, and the value is dropping over time. If you’re an investor or a central bank, you might want to consider gold as a hedge. It is considered a classic hedge against inflation because it’s a real asset that requires real resources to get out of the ground.

For example, if you have inflation, chances are your labour costs, cost of capital, and all the costs associated with getting that ounce out of the ground and then processing and shipping it all go up. What does that mean? On the margin, the cost of production goes up as well and it embeds, almost by definition, inflation.

There might be a lag, it might not be perfect, and certainly, the price of gold varies with interest rates, the cost of getting an ounce out of the ground will probably reflect the price of gold over the long run.

In segments of 40, 50 years, which some investors and central banks have, you’re probably more sure that you’ll be protected against inflation with gold than you would be by issuance of some sort of a treasury note.

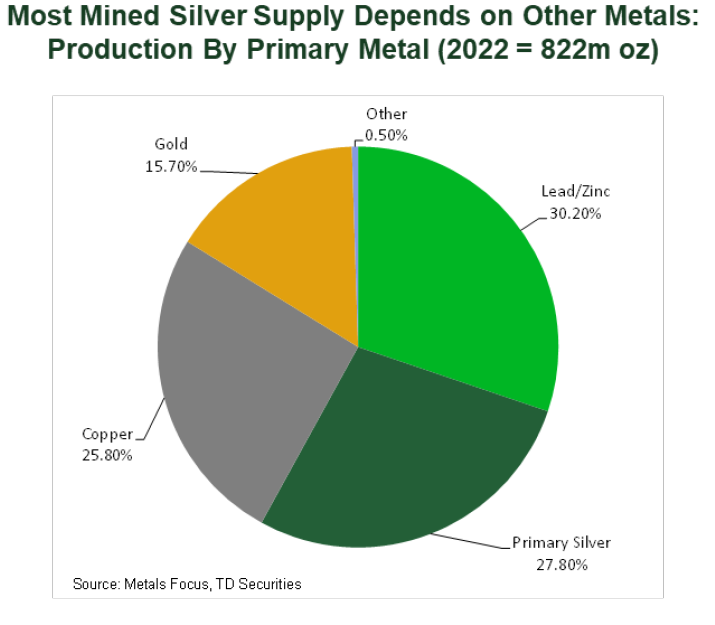

Silver is a bit like that as well, but it is also a base metal and over time it’ll become more associated with the green economy as it’s used in solar panels and in the electronics components of EVs. Silver is going to benefit from both.

As rates start dropping, probably well before we see a move towards target inflation of 2%, I think gold might then do quite well over the latter part of the year. Will it go to new records? We think it will, but ultimately, interest rates, investing purchases, and a lack of a lot of new supply probably imply that if they don’t go up a lot, they’re going to be stable for a prolonged period.