The outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 accelerated what was already rapid growth in awareness and involvement within the investment industry on sustainable investing practices. As with any trend, the approaches to sustainable investing range from financially opportunistic window dressing (aka greenwashing) to aggressively militant (shareholder activism with unintended consequences such as impacting future commodity supply).

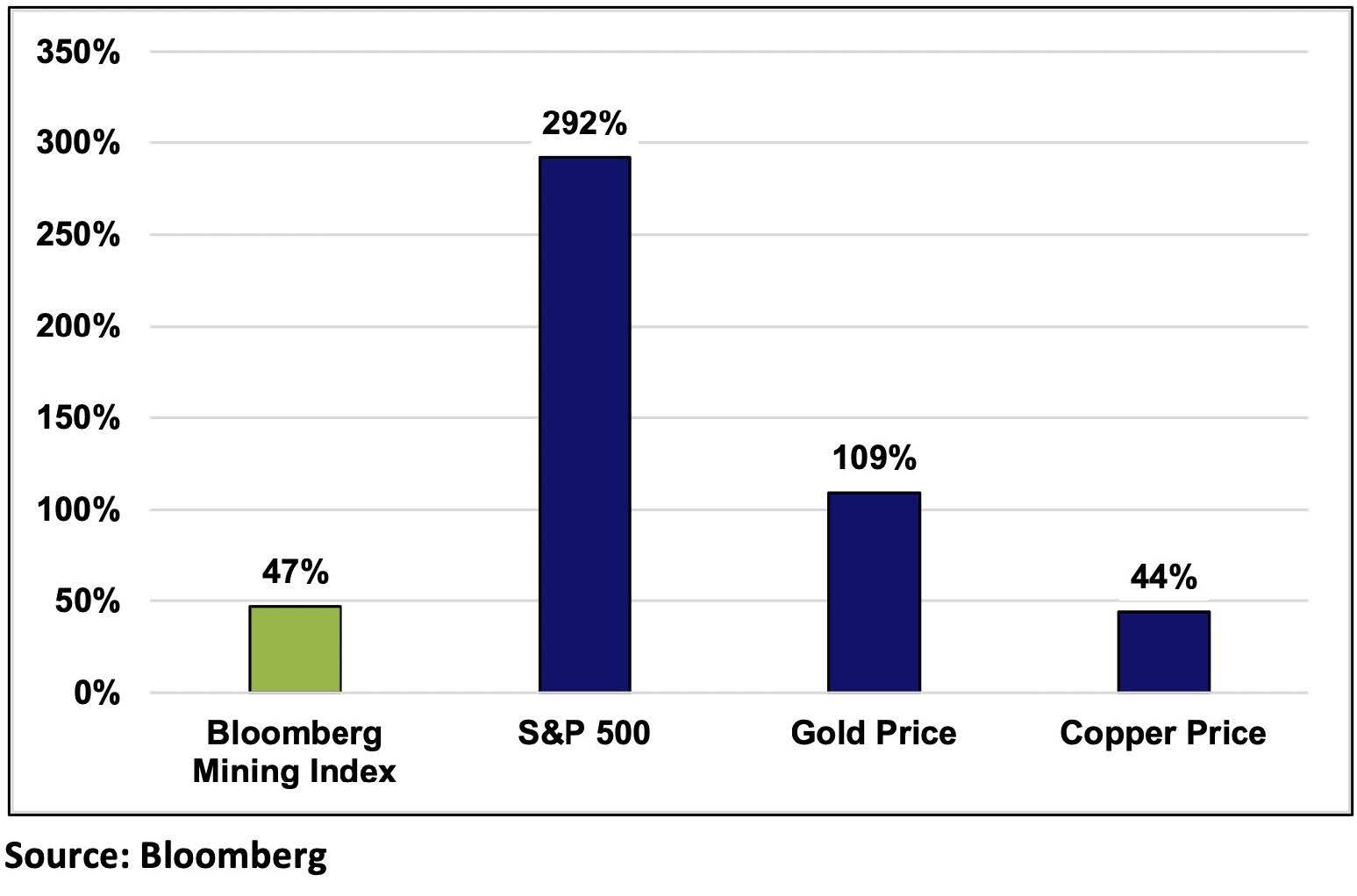

The resources sector has been particularly affected, with resource company divestment a common approach taken by investors. Over the past 15 years, the resources sector (as represented by the Bloomberg Mining Index) has generated a total return to investors of 47%, underperforming the S&P 500 (+292%) and the gold price (+109%). While there are many possible reasons for this, such as poor capital allocation and high debt levels, a key contributor, in our view, has been increased pressure on fund managers from asset owners to meet ESG ratings and sustainability criteria. Similarly, resource companies are painted with the same brush, especially by the various ESG and sustainability ratings agencies.

We believe that this approach is an oversimplification which misses some of the important sustainability nuances of resource companies, especially in Africa. Sector-based negative screening can have unintended negative consequences, such as higher inflation due to underinvestment in supply or business practices that damage local communities due limited public accountability. Sustainable Capital takes a company-specific approach which focuses on the net impact of each company and is fully integrated into our investment approach and philosophy.

An important part of Sustainable Capital’s idea generation and stock selection approach is to search for companies that are “part of the solution” rather than “part of the problem”. Companies that are “part of the solution” for all stakeholders (a definition that goes beyond shareholders to include broader society and the environment) tend to benefit from direct and indirect tailwinds that transform intangible factors into line items on cash flow statements and balance sheets.

Conversely, companies that are “part of the problem”, where shareholders are profiting at the expense of other stakeholders, tend to face long-term headwinds that lead to shareholder value destruction. These companies typically exhibit material externalities (commercial activities that negatively impact society but are not immediately captured by market prices). Obvious examples of externalities would be companies that are polluting the environment, applying poor labour practices, or benefitting from improper political affiliations. By the time these externalities move from being off balance-sheet items to on balance-sheet items, the outcome for shareholders is usually disorderly and often severely punitive.

Sustainable Capital engages directly with the management teams and boards of directors applying the levers of capital to facilitate positive changes in company behaviour. This ranges from constructive, collaborative engagement to shareholder activism.

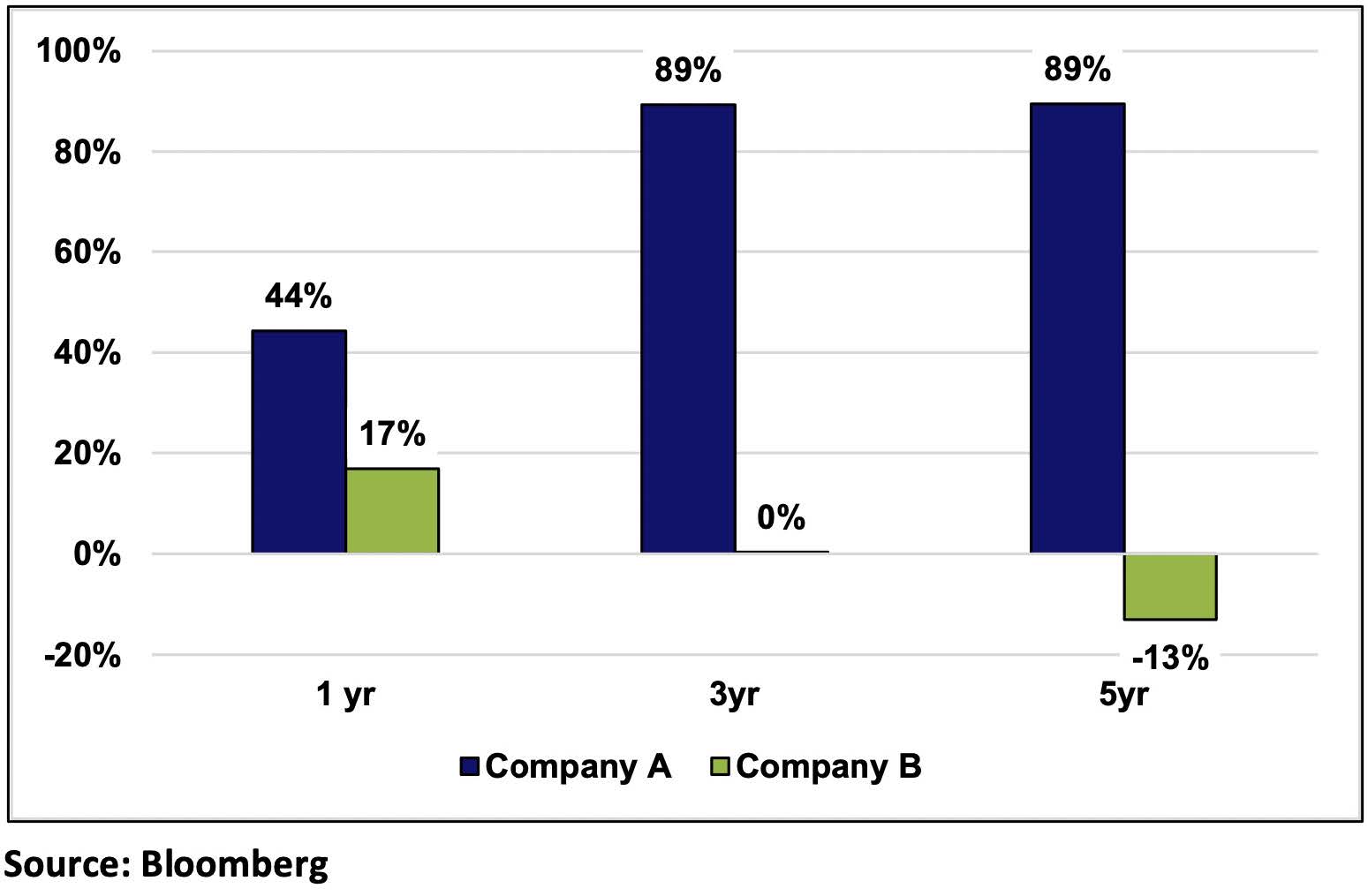

Below we provide a company specific comparative analysis to illustrate the impact for shareholders of sustainable business practices within the resource sector.

Company A is a low cost, mineral sands producer, which operates in a remote, undeveloped part of East Africa and is a responsible corporate citizen with an ethical core that has earned a valuable social licence to operate. During the decade that is has operated in this region, it has allocated a significant portion of the value generated from the mine to local community development through a combination of donations, educational training, and skills transfer. This has created direct and indirect employment in the region, improved livelihoods, and supported social mobility for members of the community who are now equipped to operate in other mining jurisdictions.

Alongside direct community contributions, the company has been a key supporter of the government’s budget through taxes, royalties, and mining licence fees. A key aspect of the government payments has been transparency (zero tolerance approach to corruption) and direct lobbying from the company to ensure that the region where the mine is located receives an equitable proportion of these payments. A top decile operational team have ensured that all of this has been achieved with limited environmental impact. As a result of these business practices, Company A has developed a well-established social licence to operate in the region. Sustainable Capital are long-term shareholders of Company A.

Company B is a gold miner with operations in West Africa, which we opted not to invest in as the business did not meet our minimum investment criteria in terms of asset quality and sustainability performance. Aside from low-quality, high-cost mining resources, the company has maintained poor relationships with local communities near their mine. This has contributed to a severe deterioration in security around the mine and halted operations on several occasions. The senior executive team have mismanaged the company for several years while rewarding themselves handsomely. This has recently culminated in shareholder activism and the subsequent removal of several board members and senior executives.

Ultimately, the market price will reflect good and bad business practices. Company A has out-performed Company B by a significant margin over several time periods. It is important to note that both companies performances have occurred during periods where gold prices and mineral sands prices have risen by 55% and 32% respectively. Despite the material return divergence, strong sustainability performance is not accurately priced by market participants and yet is materially positive.

We continue to believe that Africa’s natural resources are an important facilitator of development on the continent, which should have a net-positive impact on all stakeholders. Placing all resource companies in the same category can have tremendous net negative impacts for both local communities and development on the continent. We believe that a company specific approach can ensure that companies that have a net positive impact are rewarded and those with a net negative impact are starved of capital.

Sustainable Capital is an independent, ownermanaged asset manager that specializes in the research and management of African listed securities. Gareth Visser joined Sustainable Capital in 2017 and has been working in African Frontier listed equities for over eight years.