I would dearly love to get overexcited about the prospects for rare earths. My role is to help corporations that use critical materials identify situations where supply of those materials is about to come under pressure, for whatever reason, and prices are likely to increase. Having another thing to get excited about and work on, as was the case with lithium chemicals in 2015, would be welcome. Sadly, I do not believe that rare-earth elements fit this bill.

We’ve heard a lot about rare earths through breathless statements in the press, from both junior mining companies and government officials. Everyone likely knows the basic script: that the rare earths are “critical” and “essential” to high technology and national defense. Unfortunately, most of this is nonsense. There are a few applications in which some of the rare-earth elements are very valuable, but the amount of rare earth required is small and could be readily obtained via small-scale local production or recycling. In most applications, use of rare earths can be substituted either through a change in the materials used or a change in underlying technology.

Rare earths are not actually rare, but they are difficult to chemically separate from one another. The most common rare earths, lanthanum (La), cerium (Ce) and yttrium (Y), have low market prices but must unavoidably be separated from the higher-priced rare earths before those can be used. The result is, at least currently, an industry where increased demand for high-value materials means that the producer must absorb the cost of mining, processing, and removing low-value material that they will consider themselves lucky to sell.

China continues to dominate global production. The largest volume producer in China does this correctly, given the relatively small size of the global market, through by-product production. By-product production is a wise and cost-effective way to approach markets such as these. Baogang Group of Baotou, Inner Mongolia, operates an iron ore mine that throws off significant amounts of rare earth-bearing minerals at essentially zero mining cost. In the south of China, state-owned companies including Minmetals and Chinalco produce the so-called “heavy” rare earths from low-grade deposits of clay that are still able to be inexpensively harvested thanks to amenable hydrometallurgy. Contrary to what has been published in the press, production of rare earths can be as environmentally acceptable as any other form of mining and state-owned enterprises that have no pressure to produce greater profits and are willing to do what’s necessary to keep pollution below acceptable levels. The industry in China even accepts mineral concentrates produced in the United States and elsewhere for processing, although the availability of these concentrates may change if non-Chinese miners develop their own separation facilities.

Contrary to what has been published in the press, production of rare earths can be as environmentally acceptable as any other form of mining.

Today, the only large-scale producer that is mostly independent of the Chinese industry is Lynas Corporation, which mines ore in Australia and sends a mineral concentrate to its hydrometallurgical and separation facility in Malaysia. Lynas was financially and commercially backed by companies in Japan, including Sojitz, following the 2010 rare earths “crisis” during which, through some fairly unique circumstances, rare earth exports from China were dramatically curtailed, exports to Japan from China were cut off entirely for a few weeks, prices skyrocketed, and then demand, followed by prices, collapsed. No company can substitute away from or eliminate the use of a critical material overnight; by assisting Lynas, Sojitz and other Japanese corporations have constructed a buffer for themselves if the 2010 “crisis” recurs in some form.

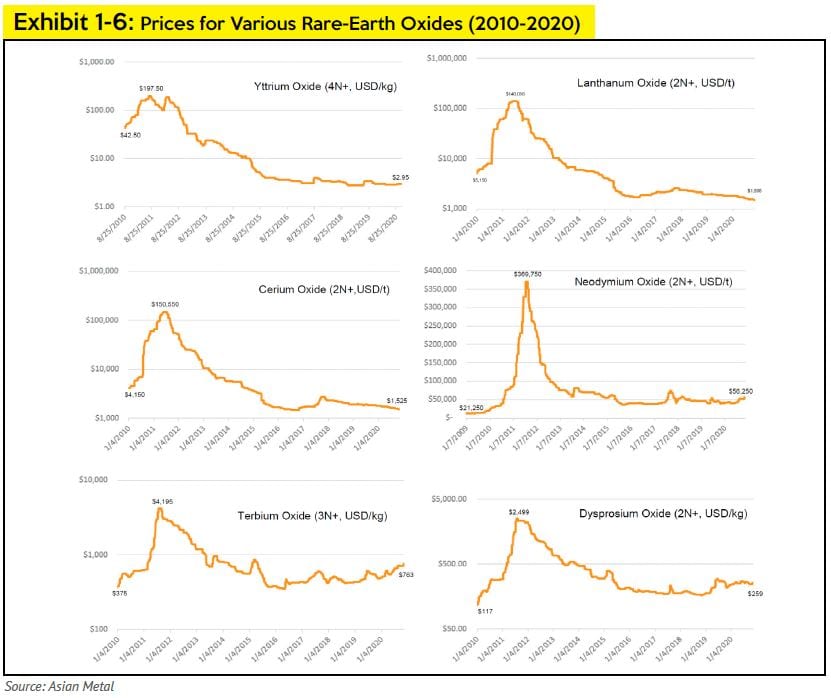

However, what such commercial arrangements cannot do is insulate Lynas and other non-Chinese producers from the challenges of pricing in this market. The result of the present market for rare earths was that during fiscal year 2020, in spite of producing 14,562 tonnes of rare-earth oxides (REOs), Lynas suffered a comprehensive loss of AUD 32 million. Truly, without the sort of market intervention in which the USA and other western governments have been loath to engage, rare earth companies must be sharply focused on their costs or they will not make money. Let’s look at the prices of some key REOs since the start of 2010 to the present day (graphs are log scale due to the large price swings):

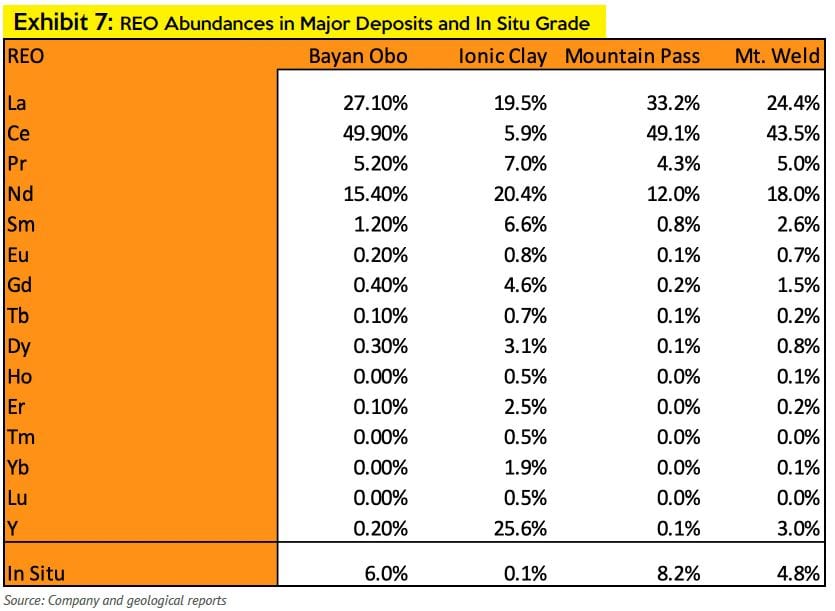

What we see in Exhibit 1-6 is that prices rose through the period of the “crisis” to unsustainable levels, then collapsed back. Some of the rare earths have higher prices today than in 2010, some have lower prices, but all of the common REOs have substantially lower prices today than in 2010. Let’s look at the abundances of the rare earths, by element and in situ grade, for four major sources of these materials, as seen in Exhibit 7.

From the above, we can see that low-value REOs like La, Ce, and Y make up 77% of what is produced at Bayan Obo in the north of China, 51% of what comes out of the south China ionic clays, 82% of what is mined at Mountain Pass in California, and 71% of what is mined by Lynas at Mt. Weld in Western Australia.

Present processing technology allows for cerium to be chemically removed, to a degree, early in the process and at a lower cost. However, the processing cost to make a kilogram of high-quality neodymium oxide for the magnet industry is dominated by the cost of getting rid of the surrounding rare earths, valuable or not. Unless and until there is a processing technology that selectively removes the desired rare earths and does so at a reasonably low cost, companies are forced to make more La and Ce, which they might not even sell, if they want to produce more neodymium (Nd) or praseodymium (Pr).

However, the current thinking holds that we are about to be swamped by demand for high-quality magnets for the automotive industry. Those buyers will be forced to pay up, and so the higher prices they pay will allow the production of more low-value lanthanum and cerium. Well, not so fast. First, it isn’t clear that governments will be able to shove electric vehicles (EVs) down the throats of buyers; even in China the penetration rate of EVs is only about 5% and that’s with substantial subsidies in place. Second, there is no requirement that the electric motor in an EV be built using rare-earth magnets – Tesla got by quite nicely for years building models that used induction motors containing no rare earths. Third, there is an upper limit to the price that can be paid for the magnets used in a motor before it simply becomes cost prohibitive to use rare earths at all. Various papers have been written on this and other substitution prices. For example, offshore wind turbines tend to favour the use of rare earth, magnet-based generators because they are less prone to breakdown than electromagnetic systems that incorporate mechanical transmissions and the like, and given that an offshore turbine can’t be accessed and repaired as easily as an onshore turbine, that makes sense. But when the rare earths “crisis” hit, the use of neodymium iron boron magnets in wind turbines collapsed because neodymium oxide prices topped USD$200/kg. Even in that critical application, cost effectiveness rules.

We believe the rare-earth industry is compelling enough for companies with high-quality deposits and low-cost positions, without requiring any baseless hype about how “essential” or “irreplaceable” the rare earths are.

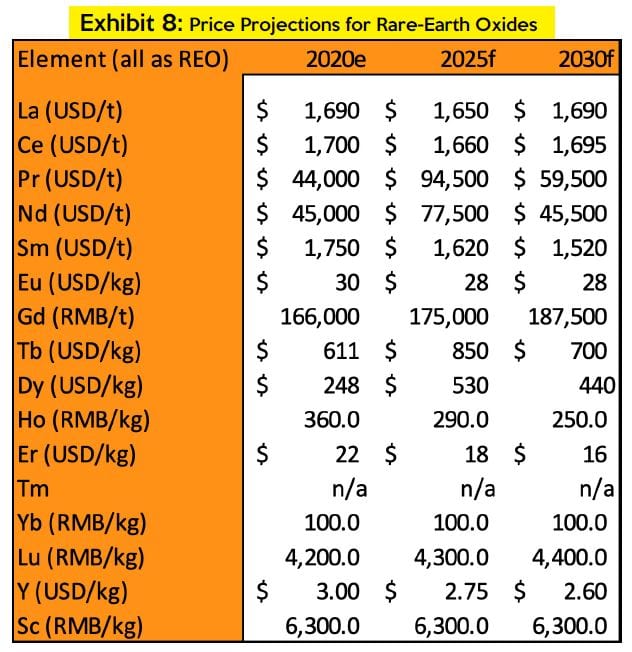

We are not implying that there is no hope for the market. We foresee demand increasing and prices slowly recovering but, barring some unforeseen event, we cannot imagine anything more than a gradual improvement in pricing. We do not believe that Chinese authorities are foolish enough to try to reenact what happened in 2010 and 2011 because that was extremely damaging to the Chinese rare-earth industry (and besides, there are far better options in terms of critical materials for the Chinese authorities to use as leverage in a trade war, for example). However, our price forecasts break down beyond 2025 because, at that point, there is insufficient supply to allow continued unfettered access to REOs, and either new supply must be entering the market or price shocks will occur. For more on this see Exhibit 8.

We believe the rare-earth industry is compelling enough for companies with high-quality deposits and low-cost positions, without requiring any baseless hype about how “essential” or “irreplaceable” the rare earths are. We learnt the rare earths were neither “essential” or “irreplaceable” 10 years ago. It is important for those involved in the space to keep a close eye on prospective new sources of rare earths, such as by-product production, and on new technology for separation, which could improve the economics of the industry either by directly lowering overall costs or by allowing production of selected REOs at lower effective cost. Rare earths are wonderful materials to have provided that you can reliably source them at a reasonable cost.