Over the past 20 or so years, nickel has been one of the most volatile of major exchange traded commodities (Figure 1). Technological and economic advances in laterite smelting in China driven by high prices and sheer necessity created a major source of new supply from the mid-2000s in the form of Nickel Pig Iron (NPI).

Less than 10 years later, regulatory change in Indonesia significantly disrupted that new supply for a while…before driving it even higher! Most recently, global determination to decarbonize has created new demand for battery materials, including nickel.

While this has materially increased the long-term demand outlook for nickel, it has also created different classes of nickel products, and growing disparity in pricing those products. Overlay all that with the usual commodity cycles, and for equity investors it has been a landscape fraught with opportunity…and risk! We are still on that journey of disruption, and we believe the coming decade will be similarly invigorating.

Figure 1: Nickel prices 2001 to present (US$/tonne)

By way of introduction, some (over) simplifications on the two key forms of nickel supply:

- Nickel sulphides used to dominate the supply side. Nickel sulphides occur in intrusive and extrusive igneous rocks, and selectively mined by either open pit or underground methods with the ore milled and floated to form a 5-20% Ni concentrate that is sold to a smelter

- Nickel laterites are economically concentrated at the earth’s surface by weathering processes. Mining is cheaper but, with more complex mineralogy, processing is generally more energy intensive and higher cost. NPI and High Pressure Acid Leach (HPAL) are two key forms of nickel laterite processing

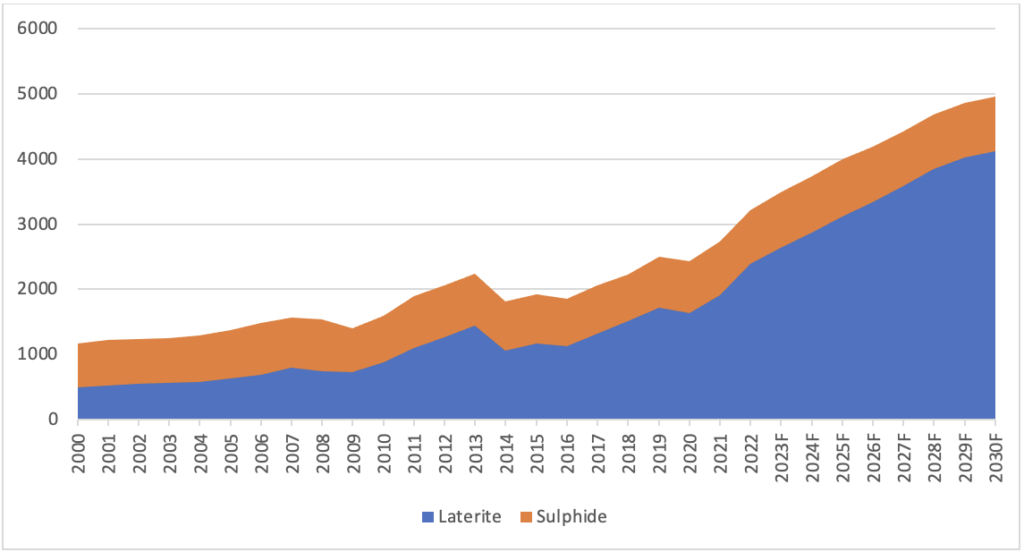

As Figure 2 shows, nickel laterites comprised 43% of global nickel supply in 2000, increasing to 74% in 2022, and are expected to be 83% of global supply by 2030.

Figure 2: Global nickel mine production 2000 to 2030F – sulphides versus laterite (kt)

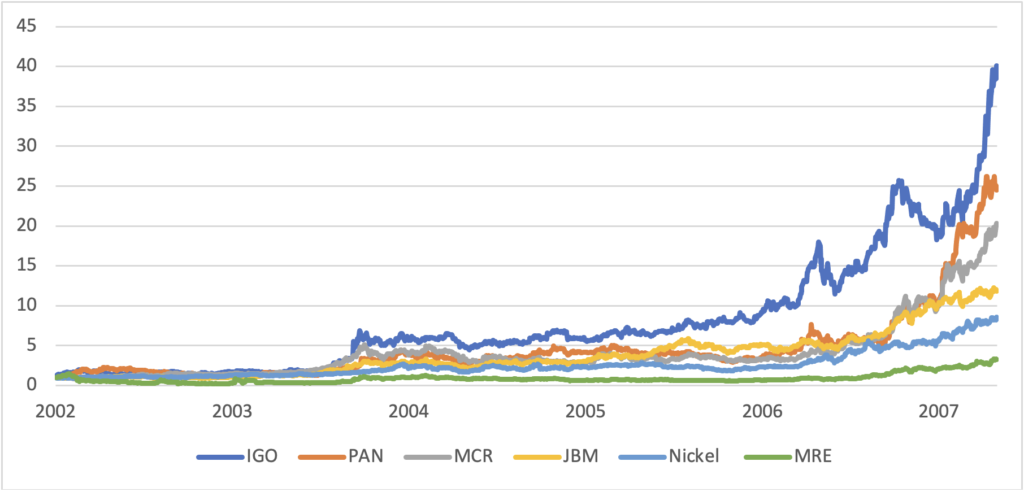

As the start of this millennium, Australian nickel equity investors typically gained exposure by investing in underground Western Australian nickel sulphide producers, such as IGO Limited (ASX: IGO), Panoramic Resources (ASX: PAN), Mincor Resources NL (ASX: MCR), Jubilee Mines NL (ASX: JBM), and Western Areas Ltd (ASX: WSA).

Back then, the early laterite producers in Australia (and elsewhere) really struggled technically and economically. Examples include Bulong, Murrin Murrin, Cawse and Ravensthorpe in Western Australia, and Goro in New Caledonia. These were all HPAL projects.

Figure 3 shows the performance of these companies from 2002 to 2007 when nickel prices increased more than eight times on explosive Chinese economic growth (especially in the commodity-intensive property and infrastructure sectors) and critically low nickel inventories. All the Aussie nickel sulphide miners outperformed nickel and were 10 to 40-times higher over the boom, while MRE, the sole HPAL producer, grossly underperformed – it was up a miserly three times!

Figure 3: Indexed performance of ASX listed nickel equities 2002 to 2007 versus nickel

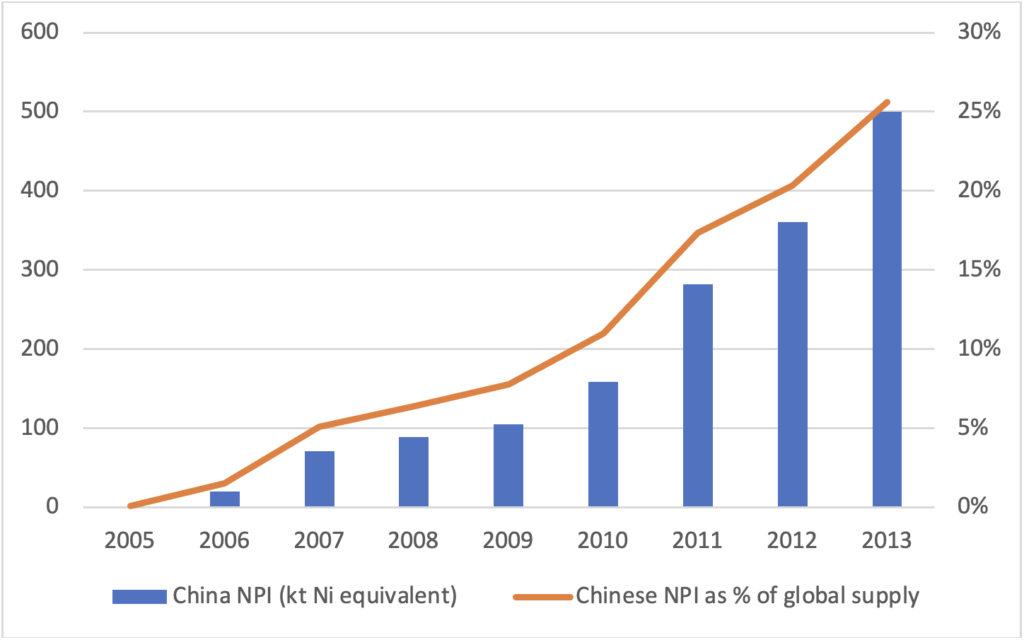

Chinese companies are innovators, and emergency nickel units were delivered in the form of NPI production. With 60 to 70% of nickel going into stainless steel production, an added benefit of NPI is that the “I” stands for iron – which was also enjoying spiking prices. Very quickly, scale and expertise drove efficiency and production growth, not unlike the US onshore unconventional oil producers who were similarly disruptive in the energy space.

Chinese NPI production went from effectively zero in 2005 to 500kt of Ni production, or 25% of global supply by 2013 (Figure 4). The new supply was a big factor in bringing nickel prices back to 2005 levels. The best cure for high prices is high prices.

Figure 4: Growth in Chinese NPI production 2005 to 2013 (nickel metal equivalent, kt)

Indonesia was the source of most (but not all) of the raw materials driving this growth. By 2014, the Indonesian government had had enough of selling low-value nickel laterite to China, and it enforced a ban on laterite exports, seeking to encourage downstream value-adding industries to operate in country. So, a big chunk of 25% of global supply was suddenly under siege and nickel prices in 2014 again began to surge.

Many in the market didn’t fully appreciate at the time the extent to which China had stockpiled nickel units in the year leading up to the ban. These hidden stocks added an invisible further overhang to burgeoning LME Ni inventories. So began a two-year price slide as the market digested excess inventories.

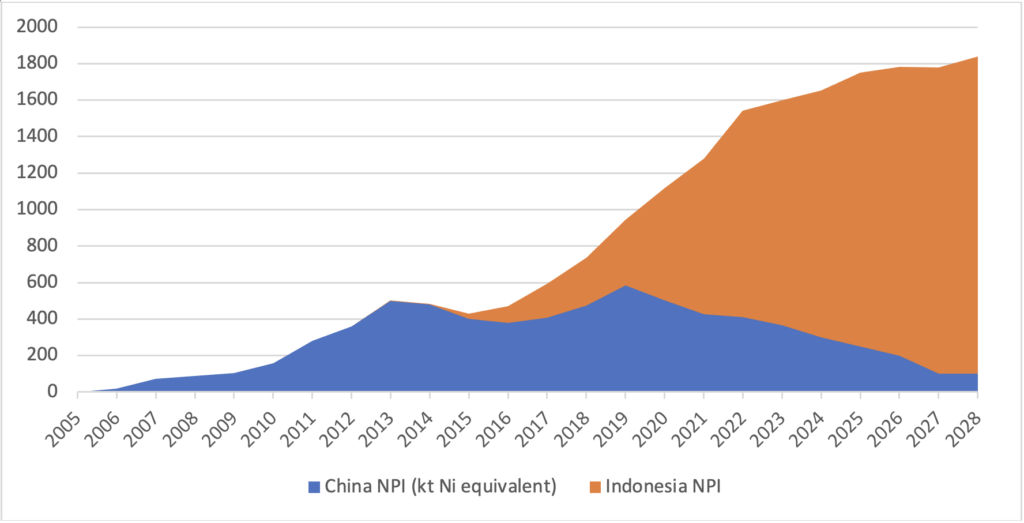

Over that following period, Chinese companies again got busy, this time building even more cost efficient NPI capacity in Indonesia to replace their Chinese capacity that was now scrambling for feed. They also added stainless steel production. This was the specific intent of the Indonesian policy, and it worked spectacularly. As Figure 5 shows, by 2020, Indonesia had overtaken Chinese annual production rates of NPI. The outlook is for continued extraordinary growth for the rest of the decade, even as NPI production in China declines steadily.

Figure 5: Growth of Chinese and Indonesian NPI production (nickel metal equivalent, kt)

Darkest before the dawn?

By April 2016, nickel was back below US$10,000/t, and 60% of global nickel supply was cash flow negative. With cost curve support, prices ground higher over the subsequent six years as LME inventories gradually declined.

Contemporaneously, nickel’s use in batteries for electric vehicles (EVs) emerged as a structurally new source of demand. In 2016 the opportunity was nascent. But technology quickly brought costs down, as did aggressive corporate and sovereign commitments to decarbonizing. If anything, COVID-19 accelerated those plans, with China, Europe and, more recently, the US mandating significant fiscal stimulus for EVs, renewable energy and battery storage. Accordingly, batteries (which in 2020 comprised ~8% of global nickel demand) are forecast to grow at CAGRs between 16% and 20% out to 2030 driven by EV penetration from ~6% to 40% over the same period.

The new normal

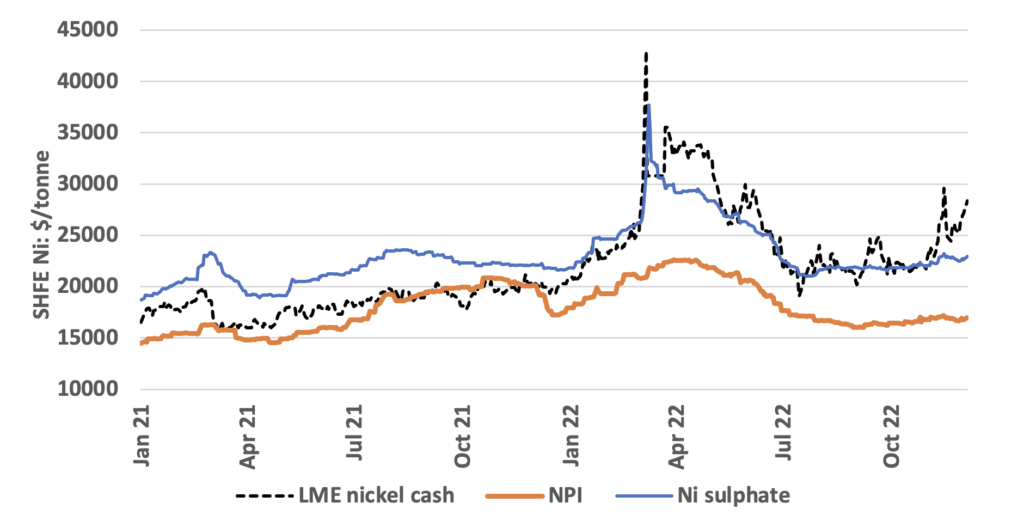

One problem: the strong growth in NPI supply was in a form of nickel that was not able to be used for the strongly growing demand from batteries. Different classes of nickel pricing emerged: Class I (high purity nickel metal or pellets, LME deliverable, suitable for batteries) and Class II (ferro nickel or NPI products). Class II is less pure and works in stainless steel, which in in 2020 was ~70% of nickel demand (but growing at more pedestrian mid-single digits).

As shown in Figure 6, the market has adapted to reflect the different underlying fundamental of supply and demand for Class I and Class II nickel, with NPI currently trading at a growing discount to LME nickel.

Figure 6: Ni metals equivalent prices for LME, NPI and nickel sulfate

Ever nimble, the nickel supply side in Indonesia had not finished its disrupting, with two additional surprises!

Chinese nickel and stainless steel major Tsingshan added capability from 2021 to convert NPI to nickel matte, for a price, which ultimately can be used in batteries. This provides a mechanism to arbitrage price differentials between Class II and Class I

HPAL processing is emerging as a potentially huge new source of Indonesian supply, leveraging off existing industrial capacity and proximal reserves of limonite, a different form of nickel laterite from that used in NPI. Most importantly, HPAL production can be used in batteries. The early western HPAL experience evokes memories of capex and opex blowouts, and production rates well below nameplate. But, as last decade shows, you bet against the execution capabilities of teams in China and Indonesia at your peril. That said, ESG-friendly energy supply, tailings disposal, and overall environmental protection remain meaningful challenges for these potentially massive projects

While all this may seem bearish for Class II and/or Class I nickel pricing, and that Indonesia may indeed be able to meet the market’s needs, European and US end users may be reluctant to access that supply unless they absolutely need to. First, Chinese diplomatic relations with the west are at a very low ebb, which includes Chinese operators in Indonesia. Secondly, the high carbon footprint, particularly of the NPI producers converting to matte, may mitigate against battery and car manufacturers contracting for supply.

As if all that weren’t enough twists and turns, on 8 March 2022 nickel spiked to an all-time high of US$100,000/t on a combination of possible sanctions surrounding the Russian invasion of Ukraine (Russia comprises 9% of global Ni supply and 20% of Class 1 nickel) and reportedly a squeeze on a very large short position on nickel into such significant distress that the LME suspended trading for the first time since 1985. To date, sanctions have not been placed on Russian nickel.

For the ASX equity nickel investor, the next 20 years should be as interesting as the last 20, with plenty of opportunities to gain exposure to the multiple nickel investment thematics. Three of the companies in Figure 3 are still around, and there are more up-and-comers just like them. In fact, for the traditional domestic underground nickel sulphide miners in particular, their product is likely to be more appreciated in the new normal: if they can control their costs, they have a competitive Class I product with a relatively favourable geopolitical and carbon footprint that the market wants.