Supply chains for key battery metals are a major topic of discussion right now, as governments and companies look to see how to secure enough metal. How do you see Canada and Canadian companies working through these issues?

The Canadian mining sector will adjust to the metals that are needed for electrification. One of the biggest challenges we face at present is that there are several metals used in batteries that are quite expensive – for instance, cobalt and nickel. I believe that, in time, they will be either completely engineered out or the amount used will be dramatically reduced in the new generation of batteries. The problem I face as an investor is that by the time a new mine is up and running, the battery technology will have changed.

That’s why the mining business is so cyclical. You get these ups and downs in the investment cycle. Going forward, I do not have a crystal ball to tell me what technologies we’re going to need for electric vehicle batteries and what the chemical composition of them will be. My approach at present is to stick with the basics; I’m sticking with copper and nickel, not the more esoteric metals.

It’s rather naive to suddenly think that everybody needs to be self-sufficient in battery metals

Do you think there is enough investment into Canadian companies to grow domestic supply? Are we excelling anywhere?

I think it’s rather naive to suddenly think that everybody needs to be self-sufficient in battery metals. The reality is that a number of countries are not suited for something as simple as lithium. In Canada, we have hard rock with lithium, but we don’t have the big brines to compete with Chile and Argentina.

Over time, the market will adapt. I’m pretty sure lithium will be one of the winners long-term. Fortunately, there’s lots and lots of lithium in the world. I think the biggest challenge for lithium is that there are a number of lithium salars globally that have some nasty metals in them, which are difficult to remove. The technology for their removal will improve over time. That’ll change the whole dynamic, but I think to have domestic supply for every single metal you need for your batteries is, quite frankly, impossible.

What type of projects are most compelling to you right now?

The most compelling are those that we are going to need – with or without electrification. For instance, nickel sulphide projects are one of my favourites, because they’re very rare. With the nickel hype right now, you’re seeing a few people running around with these fantasy projects that are completely uneconomic. They’re all hyped up in this whole battery metals thing. They are saying, “Elon Musk, we’re there for you. We’re going to find all the nickel you need.” While the reality is many of these projects will never get off the ground.

There’s been a lot of discussion recently about labour shortages and mining’s PR issues. What do you think can be done on this front to push the industry forward?

Labour shortages are not just in mining. It’s very difficult to find people right now. Frankly, I don’t know where everyone went. I see us having to slow this economy down because there does not appear to be enough people to fill the jobs and, with record low unemployment rates globally, that’s highly inflationary.

Do you see ESG concerns coming top of mind for Canadian companies and investors? Where are people focusing their efforts and what’s missing from the story?

I’m not a huge fan of ESG. I’ve seen it in the U.S., especially with some of the big money management firms focusing on ESG. They’re saying, “Well, we’re not going to invest in oil because it’s dirty.” Virtually everybody I know still drives to work with an internal combustion engine car. With the average oil well decline rate globally of about 8% per year and the lack of investment over the past six years – and possibly as far back as ten years – we are seeing the ramifications of that with oil over US$100 a barrel.

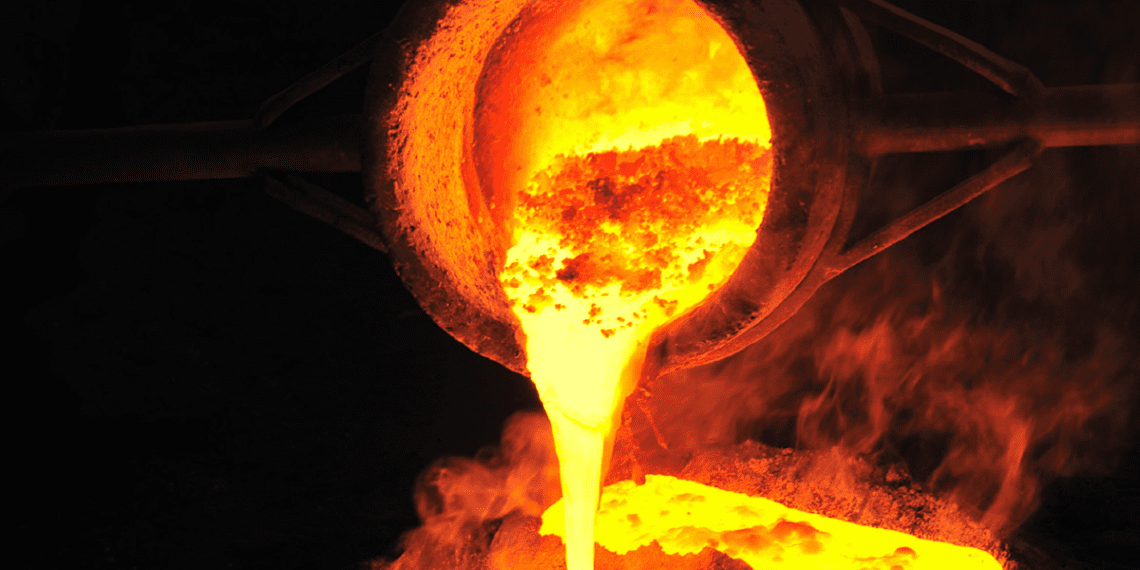

I’ve seen companies doing the stupidest things to restructure their businesses, because some of the big investment firms, especially U.S. based ones, are putting all these restrictions on them. The biggest travesty I see is companies taking certain divisions, which generate more CO2 than others, and spinning them off and somehow thinking they’re good corporate citizens, or they’re going to save the planet. Instead of them running, for example, their metallurgical coal business, somebody else is running their metallurgical coal business. Last time I checked, you’re going to need metallurgical coal to build Tesla cars, and there is no substitute anytime soon.

How has the global political unrest, such as what’s happening in Russia and Ukraine, impacted your views on commodities and investment?

Well, like I mentioned, this whole ESG movement is completely and totally outrageous. Let’s look at Germany. Germany spent a trillion dollars to move to solar and wind. They shut down their nuclear power plants. Here they are now, realizing solar and wind doesn’t work and they are going back to burning coal. The Germans now have a larger CO2 footprint than they did in the past, and they’re highly reliant on carbon fuels from Russia, of all places, too. It is truly one of the most outrageous things I’ve seen in my career.