Since the start of last year, the lead price has been on a fairly steady decrease with few interruptions, propelled downwards by external forces with its own – essentially sound – fundamentals doing little to battle this fall. As for the past two years, mine production is the key factor affecting the supply-demand balance. But, after four years of decline, mine output is forecast to reverse this trend with some meaningful growth. The unfamiliar problem for primary lead supply is now the prospect of a smelter bottleneck due to the potential for capacity outages both in China and the Rest of World (ROW).

China remains the dominate player for both lead production and consumption, and the slowing of the Chinese economy and fall in automotive production will not substantially change that. What is less certain is the ability of China to supply its own lead demand with the continuing campaign of environmental inspections and the closure of facilities failing to meet regulations. If China turns to ROW for refined lead supply, this could meaningfully denude availability in ROW at a time when exchange stocks are at their lowest for almost a decade.

The largest sector of lead demand is automotive batteries. But it is increasingly under threat from new battery technologies, new types of vehicles and ever tougher legislation. This year may prove to be a turning point in the long-term prospects for this application. But do not be too hasty in writing off the humble lead car battery – we are yet to see the peak production of internal combustion engine vehicles, and there are new developments in this old technology intended to keep it competitive and relevant for many more years.

Peñasquito – the largest of a small number of additions to mine supply

We forecast ROW mine production in 2019 increasing by about 250 kt, which is equivalent to over 10%. Approximately 90 kt of this is due to stem from Goldcorp’s Peñasquito and so developments at this mine will have a major bearing on whether the overall increase actually materialises. Is there a risk that Peñasquito will disappoint in 2019? Goldcorp updates its lead production guidance in its quarterly reports, and it trimmed its 2018 projection by 22% in October in order to reflect a delay to the increase in output in H2 2018. It remains to be seen whether or not there will be a further delay.

Glencore’s Australian mines should also produce more lead in 2019. At Mount Isa, this reflects the start-up of Lady Loretta. This was already seen to be contributing well in Q3 2018 and so the risks of this development disappointing appear modest. There is perhaps more risk associated with the expansion at McArthur River. It was initially abandoned in 2015 due to the need to re-design the waste rock dump as a result of the operation generating more non-benign waste rock than expected. Will the re-design be an immediate success? Increased production was envisaged in Q4 2018 and so we should soon have some idea about how it is performing.

Unanticipated ROW smelter shutdowns – the potential for a smelter bottleneck

Last year was not trouble-free for Nordenham or Port Pirie, and their problems have led to media speculation about potential closures. While we are confident that these smelters have long-term futures, we are not in a position to rule out temporary protracted shutdowns and so it is perhaps prudent to consider how the market would be affected by such an eventuality. With the lion’s share in China, there would theoretically be more than enough spare smelter capacity to absorb displaced raw materials. The metal balance would be unchanged if this was truly the case.

However, we are not certain that it would be quite so simple. A not insignificant proportion of the capacity in China is currently idle or operating at reduced rates due to the environmental clampdown, thus limiting spare capacity, at least in the short term. Moreover, there are restrictions on bringing certain smelter feeds into China. This country’s move to ban imports of solid waste has halted its imports of secondary raw materials. Exports of lead battery scrap to China were already banned under OECD and Basel Convention legislation. It, therefore, does not matter that secondary smelters have been hardest hit by China’s environmental clampdown.

About 70% of Nordenham’s feed is lead battery scrap and the treatment of other non-concentrate feeds, such as zinc smelters’ residues, are a core component of Port Pirie’s business. If these feeds were displaced by the closure of Nordenham and Port Pirie, they would have to be placed with other ROW smelters. There is under-utilised ROW smelter capacity as a result of cutbacks in response to the high cost, and underlying shortage, of concentrates. However, we believe that these smelters are already largely maximising their intake of non-concentrate feed as a share of total feed. Absorbing more non-concentrate feed may not be possible without also processing more concentrate.

Is there sufficient spare ROW smelter capacity to do both, and so absorb all displaced raw materials that cannot be imported by China? It is perhaps possible in theory. However, we are not certain that there would be in reality given that it would result in little or no slack, and that perfectly allocating the various feed types and qualities would be difficult to achieve. Is a smelter bottleneck possible?

Ongoing environmental clampdown constrains Chinese smelter production

Any Chinese primary lead smelters failing to obtain the essential Discharge Permit will potentially be shut down in 2019, compounded by the authorities becoming more cautious in issuing new permits. For example, the 250 kt/a Yubei smelter in Henan province has yet to restart production after failing to obtain a permit. Thus the Discharge Permit may have a profound impact on primary lead production this year.

It remains to be seen whether the Special Emission Limits will impact China’s primary lead production in 2019, but smelters will have to reduce production when severe air pollution occurs. In June last year, the 420 kt/a Yuguang smelter in Henan province had to cut capacity by 50% due to an ‘orange-alert’ for air quality.

For secondary lead production, China smelter consolidation will help maintain overall output growth. With stricter regulation and more frequent environmental and safety inspections, production from small-scale smelters is falling. New smelter capacity is now from larger-scale smelters than in the past, sometimes exceeding annual capacities of 100 kt/a Pb. However, the supply of used lead batteries is becoming tighter from this rise in secondary lead capacity, resulting in higher raw material prices and lower profits. For small-scale secondary lead smelters, falling profits may further restrict production in 2019 and, for some, lead to permanent closure.

Highlights for China lead consumption in 2019

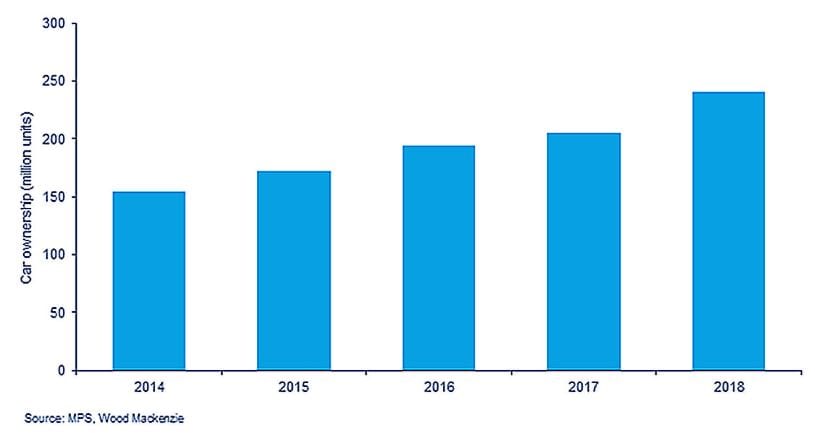

Although there has been the first drop in China’s auto production since 1990 plus restrictions on ebikes and low-speed electric vehicles (LSEVs), we still expect automotive demand to boost lead battery production in 2019. According to data from the Ministry of Public Security (MPS), China’s car ownership reached 240 million units by the end of 2018, rising by 10.5% from 2017. Demand for replacement automotive batteries will remain high, underpinning lead consumption in that sector.

The rollout of 5G networks will also support demand for lead batteries this year. According to the Chinese authorities’ economic plan, construction of 5G base stations will be one of the key issues for their ‘New Infrastructure’ plans for 2019. A rise in new base stations has been marked since October 2018. According to the latest data, China’s base station production rose by 134% in November 2018, mainly due to higher demand from 5G construction. Base stations still currently use lead batteries, but other battery technologies are now increasingly being specified as an alternative.

Automotive lead battery demand in a state of flux

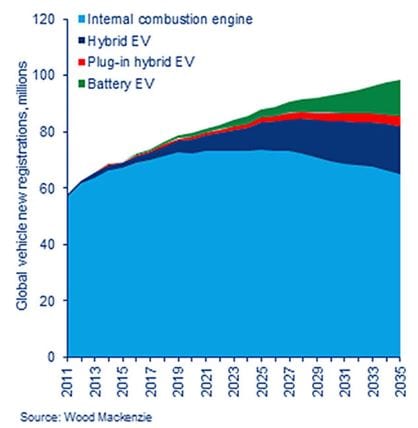

This year may well mark the point at which electric vehicles (EVs) truly become commonplace. Governments worldwide have increasingly focused on promoting EVs and their environmental benefits. Chief among these is China, which regards EVs as a key tool to tackle appalling levels of air pollution. For the first time, annual global EV sales exceeded 2 million in 2018, with roughly half in China. This is despite total Chinese vehicle sales in 2018 declined for the first time since China became a major force in automotive production. Overall sales dropped by 2.8% year-on-year to 28.1 million units, with cars down by 4.1%.

This surge in EVs needs context against an annual automotive production of around 80 million units. Despite 2018 being a record year for EVs, they still accounted for only 2.6% of total output.

EVs still use lead batteries. Lithium-ion (or sometimes nickel-metal hydride) batteries provide the energy to power the EV, but the lead battery provides the energy to control the EV. This is analogous to the Li-ion battery doing the job of the fuel tank in a regular car, and the lead battery doing essentially the same job in both types of vehicle: controlling computer and vehicle management systems, electric power for navigation and infotainment systems, the lights, electric windows, safety sensors, wipers, etc.

The key difference is that EVs use smaller lead batteries than regular internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles. Our research shows that lead batteries for battery-only EVs are typically 60% smaller than for an equivalent ICE vehicle, and 35% smaller for a hybrid EV. Thus, lead consumption for batteries is reduced, but not eliminated, by EVs.

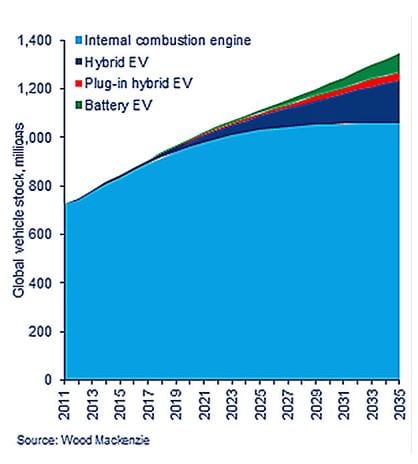

Peak global production of ICE vehicles is forecast to peak around the middle of the next decade at around 74 million units, when total vehicle production is forecast at 88 million units, after which it will decline at about 1.3% p.a. through to 2035. This reinforces that ICE will continue as the dominant vehicle type for many years to come, both for new production and the existing total vehicle stock.

At the same time, start-stop (aka. ‘idle stop’) technology is becoming much more commonplace, where the engine is stopped when the car is stationary and automatically restarted when the vehicle moves off again to reduce fuel consumption and polluting emissions. This places much greater power demands on the lead battery and our research shows that batteries for start-stop vehicles (SSVs) consequently contain about 25% more lead per battery. Most new cars sold in Europe and Japan are now SSVs, while in the US and China this figure is nearer 20% but growing rapidly. Johnson Controls Inc., the world’s largest battery producer, forecasts that globally some 50% of all new vehicles will be SSVs by 2020. This will present a substantial offset to the decrease in lead consumption from the growing proportion of EVs in use.

Crucial factors with the ability to change automotive lead demand include the price of lithium-ion battery raw materials – crucially lithium, cobalt and nickel – plus changes in the oil price and any additional legislation curtailing the use of ICE vehicles, such as some proposed total bans of ICE cars in certain cities around the world. Many of these will be subject to unpredictable geopolitical influences in the coming year.

We have LME 3mth US$ Lead Price-Forecasts available – read our ‘Inflation-Pop’ forecasts for Lead and all Base Metals – ‘WaveTrack International’ – and don’t forget one of the key drivers for 2019 and beyond will be the cyclical decline for the US$ dollar!