As humans, if we are consistent at anything, it is our inability to accurately predict the future. We are invariably constrained by the propagation of current trends and inclinations that are somehow irrevocable. It is these immutable constructs, whereby living memory plays a role in preference formation. Typically involving trends that have been around for some considerable time, but it is exactly these enduring consistencies that are the most likely to expire.

A recent example of such bias was the notion by the political elites that China would inevitably be integrated into the existing Western economic and political order (like Japan after World War II). Predicting a future outcome, based on previous trends, into a new paradigm without consideration for historical, political or geostrategic differences, is dangerous. Hubristically, we assumed that China would naturally aspire to imitate us.

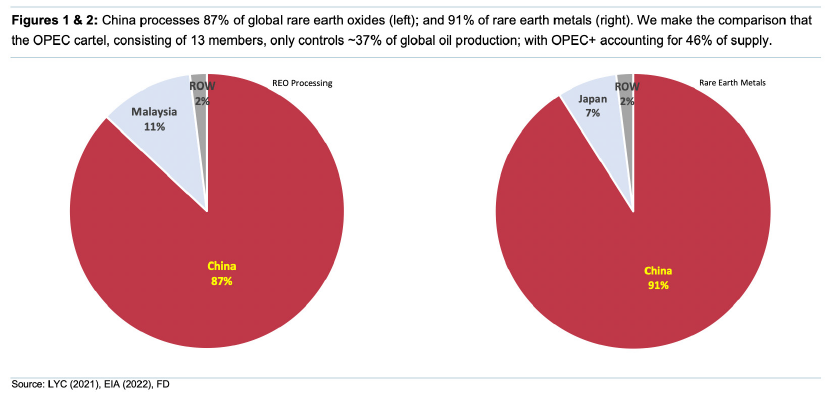

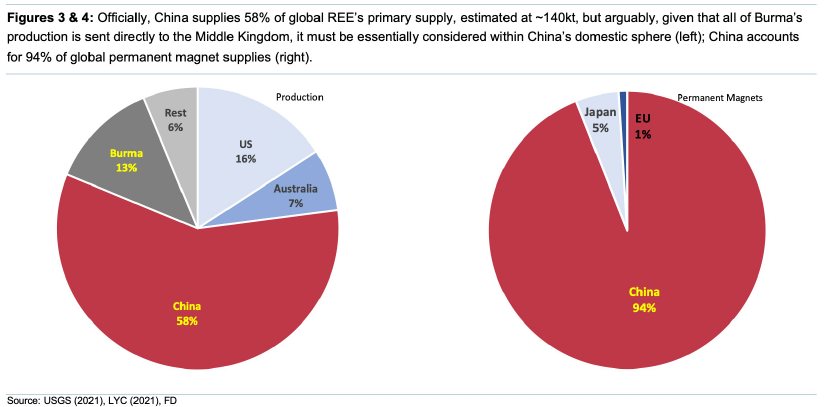

This is not a failure of analysis, but rather, of imagination. A pertinent example being the recent EU-funded blockchain certification scheme to be developed for rare earths (REEs), in an attempt to quantify the amount of carbon dioxide generated from materials used in EU manufacturing. Which, in reality, is naive to the extremis. Why? Because China effectively controls the entire REE industry (see Figures 1 to 4). Any REE purchased would most likely be sourced from a Chinese producer; where the (i) costs, (ii) source, (iii) processing location, methodology, (iv) energy utilized, and even in many instances, (v) the REE manufacturer; are all state secrets (as are virtually all commodities processed in China).

We estimate that REEs are essential for >50% of high-tech applications and are typically the enabler in transitioning (in our carbon-based economies) toward more renewable energies. Many REE elements have unique magnetic, physical, chemical and luminescent properties that allow reduced energy utilization, permitting significant efficiency gains, miniaturization, speed, durability, and greater thermal stability; and are critical in the growth and adoption of EVs globally. Underlying our world view that, in the majority of cases, there is no other realistic alternate without substantial operation degradation and/or inefficiencies. The correct context for discussing REEs, therefore, revolves around their inherent necessity, with additional cost if supply is constrained.

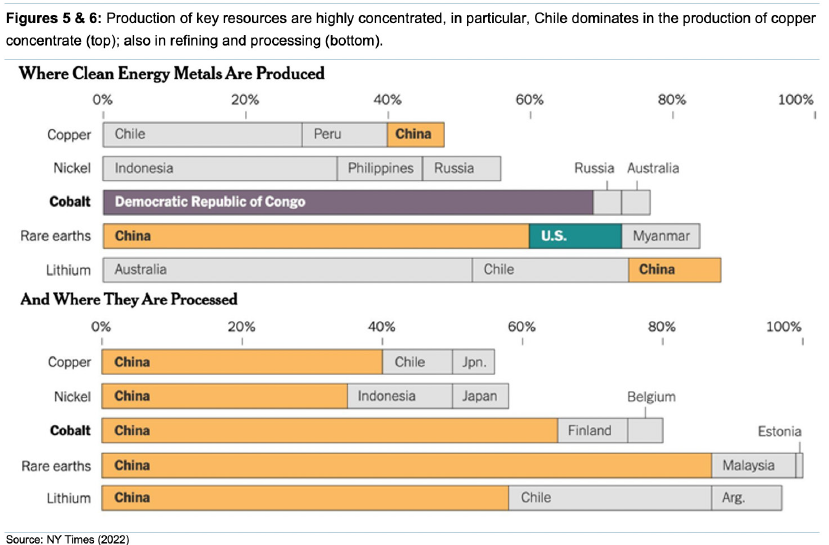

The below diagrams reinforce how incredibly naive it is to think that applying a blockchain solution to REE supplies as a form of modern-day puritanical salve in order to track emissions, given that it fails on numerous fronts. Firstly, blockchain is not some magical algorithm, it is entirely reliant on data in and data out. If there is effectively no data to input (and we can safely assume there never will be in regards to processing and refining of any commodity in China), then the process is utterly pointless, open to interpretation, and impossible to audit. Secondly, as a result of ESG and cost pressures, the vast majority of global smelting and refining of commodities has been transferred to China (see Figures 5 & 6). The difficulty with establishing alternate processing centres would be finding capital willing to compete against the Middle Kingdom’s SOEs; with virtually unlimited funding, they have historically been willing to produce below cost to drive competitors out of business.

Moreover, although imperceptible to many, is the unmistakeable global transition from the free trade paradigm (that has dominated global trade over the past 70 years), to a more mercantilist system, at the instigation of China.

Mercantilism is a practice that advocates governmental regulation of the nation’s economy to generate wealth, thereby augmenting its national power. Critical to the success of this model is the nation’s ability to exclusively secure raw materials.

In this respect, China has spent decades securing title over critical mineral deposits globally, many of which, cannot easily be replicated. Resource-based theory, in essence, stresses that the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. China has, in many instances world-class resources that are valuable, rare, difficult to imitate, and are non-substitutable; but even more importantly, China is in a dominant position of downstream processing and manufacturing in order to create a cohesive value chain.

China is in a dominant position of downstream processing and manufacturing in order to create a cohesive value chain

A model not dissimilar to what occurred in 18th century Great Britain, whereby its colonies were the supplier of raw materials, allowing it to become the exporter of finished products. So much so, that by 1840, this little wind-swept Atlantic island in north-west Europe, virtually devoid of any essential commodities, became the world’s only fully industrialized nation; with British output representing just under half the total of the world’s industrial capacity.

The key flaw of course, under the current WTO economic framework, is the theory that any resultant commodity shortages that do appear will be resolved via the “Law of Supply”, which suggests, ceteris paribus, that as the price of a good or service increases, the quantity of goods or services that suppliers offer will increase. However, in the event of capitalism, with “Chinese characteristics”, it does eventually transition into a type of hybrid mercantilism, leading to some uncomfortable conclusions being drawn. Namely, (i) in regards to critical commodities (e.g. REEs, nickel, lithium, cobalt), no matter what the price point, it better serves the mercantilist to withhold supply so as to prevent your opponent from competing; that (ii) nations without recourse to particular natural resources will have to endeavour to find technological adaptions to get around certain shortfalls, but these will (in most instances) inevitably result in higher input costs and suboptimal outcomes; (iii) China will be able to leverage resource scarcity in a number of key areas, in order to retain and possibly grow its manufacturing prowess, to the exclusion of all others; and (iv) the rise in China’s economic dominance will increasingly allow it to impose its political will on countries dependent on selling materials into its domestic market.

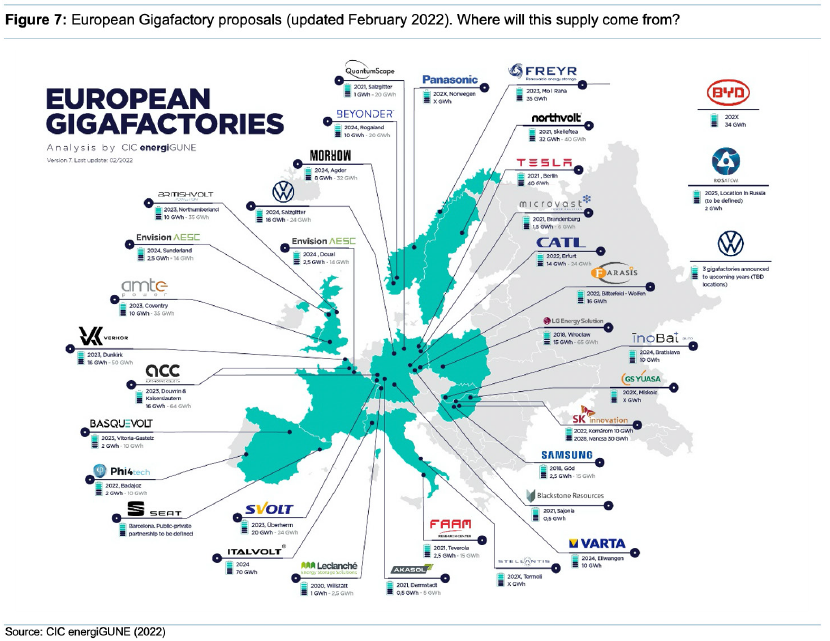

Europe, in particular Germany’s manufacturing prowess, is entirely dependent on raw material imports. There are numerous proposals to build gigafactories throughout Europe (see Figure 7), with legislation in most jurisdictions to mandate total EV adoption by 2035. The false premise behind this economic transition was the assumption that the raw ingredient, lithium, would always be available for sale. Under mercantilism, this assumption becomes a fiction, as it is in the best interests of the nation state to secure exclusive rights to various raw materials, in order to enhance its own manufacturing base, value add, export and run trade surpluses. In this instance, would it not be more advantageous for China not to sell the lithium carbonate/hydroxide, but the battery packs instead; and eventually, the EVs themselves?

The great irony, of course, is the EU establishing mandated guidelines, without security of supply. This will allow China (and other manufacturing centres) to develop a technological edge to the detriment of the Europeans. We acknowledge that there are alternative domestic sources of lithium, particularly from large Li-rich brine basins, but their extraction will be expensive, and the resultant tonnages will (at best) be modest compared with underlying demand. If this scenario plays out, the financial impact on advanced European industrial countries, including Germany, Holland, northern Italy and Sweden, will be particularly hard.

We maintain that there is a certain level of ESG insanity when conducting blockchain analysis on any strategic commodity you neither control nor even (in certain circumstances) acquire.