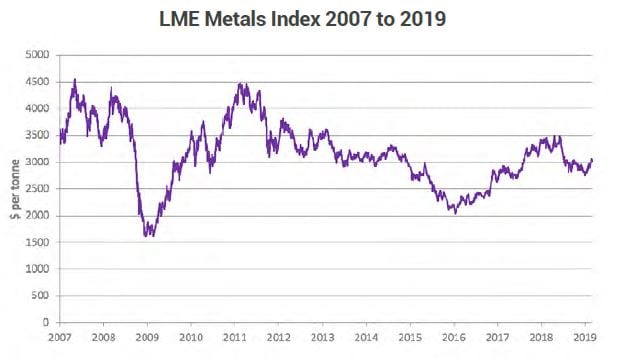

The upward trend in base metals prices paused in the early part of 2018 after prices had risen in 2016 and 2017 by an average of 95% from their 2015/2016 lows.

That pause turned into a sell-off when business and investor confidence evaporated in response to an escalation and a subsequent entrenchment in US/China trade disputes. A lack of progress in trade talks, combined with President Donald Trump’s use of tweets to voice his opinion, which undermined confidence greatly, led to price corrections – the base metals were down by an average of 30% by the time they had bottomed out late in 2018 and early in 2019.

Last year the rug was pulled from under the strong global economic recovery that started in 2016. Will the economic downturn now turn into a broad-based recession or will a trade deal come about soon enough to rekindle growth in the global economy?

While there are many uncertainties affecting the global economy, not least of which remains the unresolved US/China trade dispute, there are also lingering trade disputes between the US and other trading partners, including the EU and India, as well as uncertainty around Brexit and the standoff between the US and Iran over Iranian oil exports. All of these could add to the headwinds facing global growth. The base metals are enjoying a generally bullish backdrop where demand is holding up relatively well but supply remains tight, even if the supply deficits this year are not forecast to be as large as they have been in recent years.

The other lurking bullish factor is that the downstream supply chain destocked into the 2018 price sell-off; with confidence still weak in the absence of a US/China trade deal, the supply chain is living hand-to-mouth, which means the potential for restocking remains. This is especially the case where supply/demand balances still point to supply deficits; with the markets generally having been in deficits since 2017, stocks are in most cases not high.

According to forecasts published in our Base Metals Market Tracker, Fastmarkets expects all the base metals to remain in a supply deficit this year and all but zinc to remain in a deficit in 2020. For copper, nickel, lead and tin, this means by the end of 2020 they will have been in a supply deficit for four years (2017-2020); for aluminium a deficit of three years (2018-2020); and likewise for zinc (2017-2019).

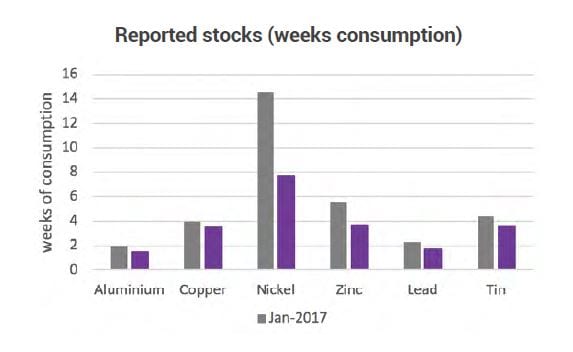

These long periods of deficits have drawn down stocks that had built up following the great financial crisis and the weak economic period that followed. This stock drawdown has made the markets notably leaner and, given a smaller cushion of stocks, prices are now likely to act more closely in accordance with their fundamentals.

Fastmarkets estimates total reported stocks per metal in terms of how many weeks’ consumption they cover at 3.5 weeks for copper, 1.5 weeks for aluminium, 7.7 weeks for nickel, 1.7 weeks for lead, 3.7 weeks for zinc and 3.6 weeks for tin.

Since around three weeks of stocks are generally considered to be “normal”, nickel stands out as still having high inventories. Still, its stocks have also been falling at a fast pace, which highlights the extent of the supply deficit. While total reported nickel stocks were recently at 7.7 weeks of consumption, they had been at 14.5 weeks two years ago.

The rapid fall in nickel stocks reflects anticipation of strong demand for nickel from the electric vehicle (EV) industry. The use of lithium-ion batteries in EVs is rising rapidly – even before EVs have become mainstream. But due to the fact that of the four main nickel raw materials that make up nickel supply only two are currently suitable to make the nickel sulfate the lithium-ion battery industry needs – and with investment in these two supply streams limited due to the low nickel price – refined nickel stocks have been drawn upon to make nickel sulfate. This is causing a fast depletion of refined nickel stocks either to make nickel sulfate or to secure supplies so that nickel sulfate can be made in the future.

This interest in refined nickel has boosted nickel prices so far in 2019. Nickel prices are leading the gains on the LME this year – its prices are up 29% since an early-January low while gains across the other base metals have averaged 16.4%.

Zinc has been the second strongest-metal so far this year. Its price rise of 23% seems counter-intuitive because of a large supply response this year, with new supply coming on-stream from New Century Zinc and Dugald River among others. Still, Fastmarkets’ research team still expects the market to be in a supply deficit this year before it returns to a supply surplus in 2020.

Zinc was also one of the metals that was hit the hardest on the way down last year. Its price fell 37%, the extent of the correction reflecting anticipation of the supply response, but it looks as though the bearishness ran ahead of the fundamentals. Fastmarkets expects the zinc market to be in a supply deficit of 145,000 tonnes this year.

The tin price has rebounded by 20% since last November’s low because some exports from Indonesia have been disrupted as of mid-October last year. But with the factor disrupting exports now resolved, exports are set to flow again, which should ease the tightness in the market. LME stocks stand at 1,230 tonnes; the average in 2018 was 2,565 tonnes. But while there is little stock cover overall given that the market is expected to remain in a supply deficit, a rebound in exports may alleviate nearby tightness.

Lead has been the fourth-best performer – its price has risen 16%. Unlike sister metal zinc, there is little new lead production coming on stream; many of the new zinc mines have unusually low lead grades.

Fastmarkets expects lead supply to grow by just 1.6% in 2019, which will be in line with growth in lead demand. With the lead market having been in a supply deficit in recent years, lead stocks are low, which should underpin the price. As well, environmental clampdowns in China on the illegal recycling of lead acid batteries are likely to reduce supply to secondary lead smelters, which in turn could keep the lead market tight. The copper price has rebounded by 14% from the early-January lows. Given limited new supply capacity in the pipeline, it is somewhat surprising that copper has not been one of the stronger performers. The longer-term outlook is bullish – in 2019, the main increase will come from First Quantum’s 350,000 tpy Cobre Panama mine, which is expected to produce 150,000 tonnes of copper in concentrates by the end of the year. But a 100,000-tonne cut at Glencore’s Mutanda mine due to lower ore grades and higher taxes in the DRC will partially offset the increase, as will the halts to production at ERG’s Boss Mining in the DRC and its Chambishi smelter in Zambia.

While total copper stocks are just above what is considered a typical level, exchange-held copper stocks are relatively low at 400,000 tonnes, which represents about 1.6% of annual consumption. As well, stocks on the London Metal Exchange have fallen to 120,000 tonnes, of which only 27,000 tonnes are available to provide liquidity in the LME system because 78% of LME warrants are cancelled, meaning the stock is earmarked for withdrawal.

This is creating tightness in the market – nearby prices for cash delivery are trading at a premium of $65 per tonne to the copper price for delivery three months forward, a situation referred to as a backwardated market. Despite the backwardation being present for more than three weeks, the higher cash price has only attracted 8,000 tonnes of copper into LME-registered warehouses; over the same period, 35,000 tonnes have been delivered out of the LME warehousing system.

The aluminium price has climbed the least this year, rising just 8.4% from the lows in January. Demand for aluminium – a metal with a large and diversified consumer base – is closely tied to swings in global economic growth, which has weakened over the past 12 months, reflecting the impact of trade disputes and a slowing in the allimportant automotive market.

Still, as well as its diversified consumer base, aluminium is seen as an environmentally friendly metal that tends to enjoy stronger growth than copper, lead, zinc and tin – it is still gaining market share in areas where it can be utilized. The big change in aluminium in recent years has been on the supply side. With China now focused on the environmental impact of industry, the littlecontrolled rollout of new capacity of the past is no longer the case – new capacity is only permitted if old capacity is removed. This has slowed the pace of aluminium supply growth in China, thereby reducing the threat of oversupply. Supply deficits have caused stocks to be drawn down, with LME stocks falling to 1.23 million tonnes from an average of 2.44 million tonnes in 2016.

With limited new supply and low prices failing to encourage much capital expenditure in base metals in recent years (apart from in zinc) and with stocks falling, the markets could tighten up quickly. Crucial will be how quickly the global economy receives a boost from any new US/China trade deal or whether the political impasse allows the global economy to deteriorate further.