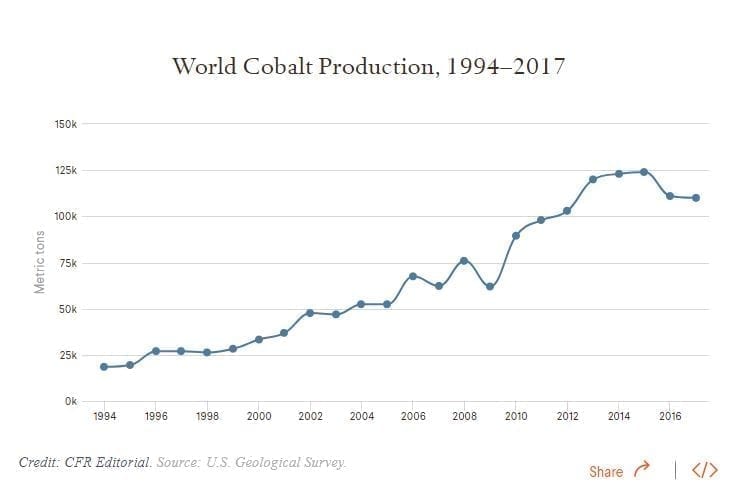

The market for cobalt has exploded in recent years, with demand driven by the surge in production of batteries for electric cars. Its strategic importance will only grow, experts say, as carmakers aggressively scale up production of electric vehicles in the decades ahead.

The boom has focused attention on cobalt’s complex and controversial supply chain. In particular, the dominant roles played by both China and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) have raised major concerns about ensuring supply of this increasingly valuable commodity.

What is cobalt?

Cobalt is a metallic element prized for its strong magnetism, hardness, and resistance to extreme heat and corrosion. The vast majority of it is obtained as a byproduct of copper and nickel mining.

In earlier centuries, artisans used cobalt as a base for glass and pigments, the most well known of which is bright blue. Today, cobalt’s unique qualities make it suitable for use in a range of highly manufactured products, such as batteries, turbine blades, aircraft engines, and medical implants and prosthetics. It is also used in petroleum refinement.

Roughly half of cobalt produced globally today is used in rechargeable lithium-ion batteries, which power everything from electric vehicles to smartphones, tablets, and laptop computers.

What’s driving the cobalt boom?

The electric vehicle, which requires a large amount of cobalt to produce, is the primary force propelling the cobalt boom. Electric car batteries require between five and fifteen kilograms of the metal, roughly a thousand times the amount in smartphone batteries.

Most global automakers are ramping up production of electrics in response to falling battery costs and aggressive government regulations, particularly in China, the world’s largest and fastest growing car market. Although electric vehicles make up less than 2 percent of auto sales today, analysts say they could account for more than half of new car sales by 2040.

How much is demand expected to grow?

Global demand for cobalt in the battery sector alone has tripled since 2011 and is expected to continue on this trajectory, rising from 46,000 metric tons in 2017 to around 190,000 metric tons by 2026, according to the industry analyst Benchmark Mineral Intelligence. The price of the metal has also soared, reaching more than $30 per pound by late 2017, up from an average of $18 in 2011.

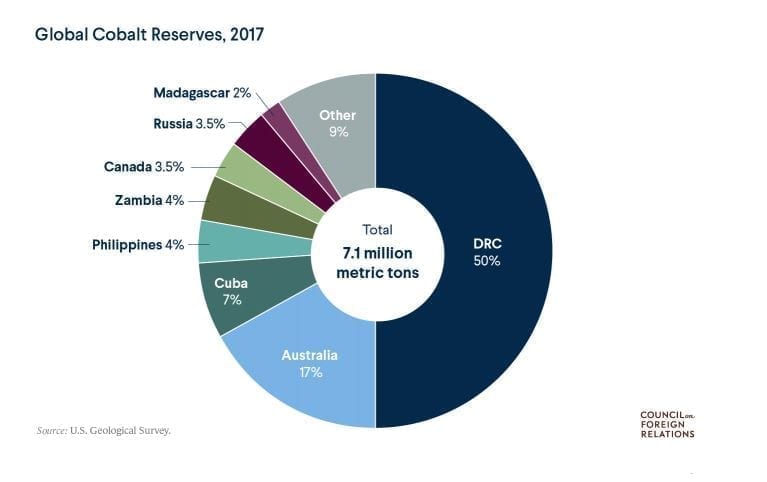

Where are the world’s known cobalt reserves?

Most of the world’s cobalt supply comes from the DRC [PDF], part of Central Africa’s copper belt. The southeastern city of Lubumbashi, in Katanga Province, is viewed as the country’s mining capital.

Australia and Cuba have the second- and third-largest cobalt reserves, respectively, followed by the Philippines, Zambia, Canada, and Russia. The United States is far down the list, holding just 23,000 metric tons in reserves.

What does the cobalt mining industry look like?

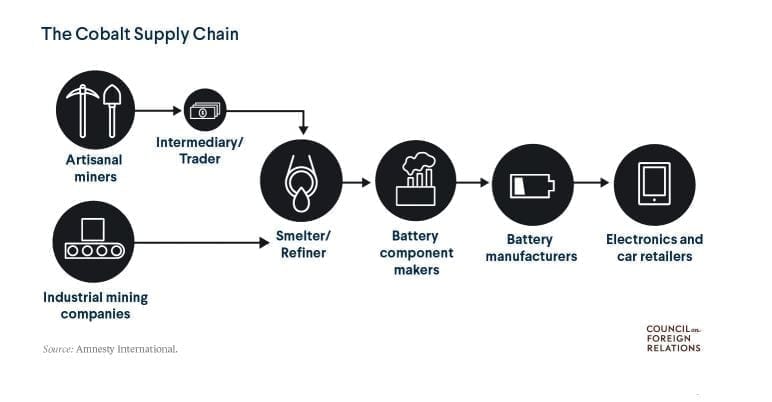

The government in a country with cobalt reserves, such as the DRC, grants permits to a small number of mining companies. Dominating the cobalt extraction market are the Swiss firm Glencore PLC and China Molybdenum Co., among a few others. Once granted rights to a particular site, Glencore, as one example, extracts the cobalt during copper mining and sells it to a battery chemical processor, most likely a Chinese firm, such as Zhejiang Huayou Cobalt. This company sells the refined product in its chemical form to a battery component manufacturer, which then sells its product to a battery maker, say South Korea-based LG Chem or China-based CATL.

Artisanal miners in the DRC, known by the French word for diggers, creusers, are responsible for up to one-fifth of the cobalt coming out of the country, adding yet another facet to the metal’s complex supply chain. There are roughly two hundred thousand creusers [PDF] in copper-cobalt mines, according to government figures, though two million people may be mining various minerals across the country. In 2014, the UN Children’s Fund estimated that forty thousand children were working in mines. The government opened the industry to creusers following the collapse of the state mining company in the 1990s, though they are restricted to sites where industrial mining is not viable.

What are some of the industry’s challenges?

Rigid supply. The cobalt industry is generally considered inflexible because production depends almost entirely on the economics of copper and nickel mining. This means that rising global demand for cobalt is not enough to drive more cobalt mining, especially if prices dip for the base metals. (As of 2015, the only place where cobalt was the principal mineral mined was Morocco.)

DRC political risks. Many industry analysts, companies, and governments have raised concerns over the concentration of cobalt mining in the DRC, which has long been plagued by corruption and political volatility. Should instability disrupt mining operations, no other country would be able to increase production enough [PDF] to meet global demand, write experts from the U.S. Geological Survey.

Chinese supply-chain dominance. Chinese firms produce more than half of the world’s refined cobalt and more than three-quarters of the world’s cobalt chemicals—the form needed for lithium-ion batteries—and many non-Chinese manufacturers are worried about their future access to the mineral. “If push does come to shove, the cobalt that is already in China will stay in China, for Chinese producers, rather than exported to external battery companies,” says Caspar Rawles, a cobalt analyst for Benchmark.

Human rights and environmental hazards. Advocacy groups have raised alarm over unsafe working conditions and the use of child labor in mines, particularly in the DRC, as well as environmental damage, including air and water pollution. The DRC’s artisanal mining sector is virtually unregulated, allowing rebel militias and corrupt government soldiers to control mining sites. As a result, many workers are vulnerable to injury, long-term health problems, and death.

How are the various industry players responding?

Faced with increased competition and the possibility of a cobalt crunch, car and battery makers such as Panasonic, Samsung, Tesla, and Volkswagen are jockeying to secure a steady supply. Some manufacturers are going directly to the source instead of component suppliers: In 2018, both Apple and Samsung were reportedly in negotiations to buy long-term supplies of the metal directly from miners, a kind of deal that Benchmark’s Rawles says may become more common as the global supply tightens. At the same time, German automaker Volkswagen signed deals with several Asian firms for tens of billions of dollars worth of battery components. Some of the largest battery makers are seeking to avoid the Kinshasa-Beijing supply chain altogether, turning instead to Australia and Canada, countries with more modest cobalt reserves, to diversify their sourcing.

In the DRC, President Joseph Kabila has sought to take advantage of the cobalt boom: In March 2018, his government increased royalties and taxes on mining firms with the aim of boosting state revenue. However, some analysts, such as researcher Ben Radley, argue that mining companies will likely use controversial accounting practices to avoid the new taxes.

Meanwhile, China sees electric cars as a strategic industry, and it is pursuing a range of policies intended to put the country in a dominant position, including vehicle subsidies, production quotas, and higher fuel economy standards. It has also made moves to lead oversight of the cobalt supply chain. In 2016, its chamber of commerce for metals established the Responsible Cobalt Initiative, comprising more than two dozen member companies, including Apple, BMW, Dell, Huawei, LG Chem, Samsung, Sony, and Volvo. Other groups are exploring the use of blockchain technology to track the cobalt supply chain.

President Donald J. Trump has sought to prevent the United States from becoming reliant on foreign mineral resources, including cobalt. In late 2017, he directed federal agencies to identify new sources of “critical minerals” and increase domestic mining and production. Cobalt is also among more than two dozen raw materials [PDF] the European Union has declared “critical,” noting the risk of supply shortage and potential repercussions for the region’s economy.

Are there alternatives to cobalt?

Research into decreasing the amount of cobalt in lithium-ion batteries or replacing cobalt with alternative metals or compounds in batteries has swelled in recent years. As one example, some battery makers have explored boosting the amount of nickel in electric car batteries to take the place of some cobalt.

Experts warn, however, that they may not be as cost-effective and that, without the same qualities that make cobalt such an attractive component, replacing the high-demand metal with something else could jeopardize product performance. Feasible alternatives using less cobalt are years away, while wholly new battery technologies may not be ready for commercial testing for decades.