This article gives a brief overview of the Australian mineral resource sector and the Australian Securities Exchange (ASX), including the history and where we are now. As I will discuss, Australia is a major global producer of a large number of mineral resources and, as such, has a strong, skilled, and successful exploration and mining industry, developed over a long history of prospecting, exploration, and mining. An explanation needs to be made of the usage of the term ‘colony’ in this article – until Federation on 1st January, 1901, Australia consisted of six selfgoverning British colonies; the first being New South Wales, and successive ones being founded throughout the 19th century.

Federation led to the current Commonwealth of Australia, comprising of six states and two territories. Given the bulk of my experience, I have deliberately concentrated on minerals, and have not discussed the energy sector, despite there being a large number of energy explorers and producers listed on the ASX (and operational in Australia and globally). The article will also focus on Australia, behind Qatar, being the second largest global exporter of LNG.

A Very Brief History of the Australian Mining Industry

Australia has had a long and colourful history of mining, with the first modern mining being for coal at Newcastle (now the world’s largest coal export port), and with the first exports of Newcastle coal (to India) in 1799, just 11 years after the arrival of the First Fleet at Sydney Cove in January 1788. Australia is now a global powerhouse in coal. New South Wales and Queensland are the main producers, with 2017 exports of some 390 Mt of both thermal and metallurgical products.

The first recorded metal mining was for lead at Glen Osmond in 1841, in what is now South Australia (and which was then part of the colony of New South Wales), with copper soon following; firstly at Kapunda in 1842 and then Burra in 1945. 1945 also saw mining at Copper Hill in the Central West of New South Wales, hosted in the Palaeozoic Lachlan Orogen, a major mineralised province, which hosts major Au and Cu-Au deposits including Cadia and North Parkes. However, it was the gold rushes of the 1850s, which comprised Australia’s first gold boom, that seized the public’s attention, with the New South Wales rush following the discovery of gold near Bathurst in 1851, and the newly created Colony of Victoria following discoveries north-west of Melbourne in the same year. Within 10 years, Australia was producing some 40% of the world’s gold. The rushes caused significant social upheaval and an influx of mi- grants, including ‘49ers’ from California.

The Victorian gold fields have historically been one of largest producers globally, producing some 80 Moz. The state is the focus of renewed gold exploration and mining, particularly given the recent successes at Kirkland Lake’s Fosterville Gold Mine. Gold was first discovered in Western Australia in 1880 at Kalgoorlie, with other colonies also enjoying their own rushes, leading to resurgence in gold production in the late 1800s/early 1900s. However, it was not until the modern Western Australian renaissance in the early 1980s that Victoria was surpassed in terms of total gold produced historically, with Western Australia accounting for 70% of Australia’s annual gold output.

The modern rush was triggered partly by the abolition of the gold standard in 1971, and the development and widespread adoption of carbon-in-pulp (‘CIP’) and carbon-in- leach (‘CIL’) cyanide treatment processes.

The modern rush was not just limited to Western Australia though; major deposits have been found in most states, commonly through revisiting historic workings. The genesis of one of the world’s major diversified miners, BHP-Billiton was in the Broken Hill Pb-Zn-Ag deposit, one of the world’s largest and highest grade Pb- Zn-Ag deposits. Broken Hill is in Western New South Wales, and was initially staked in 1884 by Charles Rasp, a boundary rider, with a syndicate of seven (including himself) forming the Broken Hill Mining Company. Mining commenced at Broken Hill in 1885, and the deposit has reportedly produced over 120Mt of high-grade ore. The same period saw the pegging of Mt Lyell in Tasmania in 1883 which was initially mined for gold, but later for copper, and operated until 2014. The west of Tasmania is a highly mineralised province, hosting several significant base and precious metal resources. The latter half of the 19th century also saw several other discoveries in various parts of Australia, including the initial ones at Cobar in western New South Wales.

Although disrupted by two world wars and the Great Depression, the first half of the 20th century saw intermittent periods of prospecting and exploration, with a number of major discoveries being made. One such discovery was Mt Isa in 1923, resulting in the formation of Mount Isa Mines (MIM), which, for in a brief period in 1980, was Australia’s largest company. My recollection, from the early 1990s as a young geo working for MIM Exploration, was that in the early 90s, miners dominated the top of the bourse, unlike now when it is dominated by the banks. Mt Isa, which contains both Pb-Zn-Ag and Cu orebodies is a Tier 1 deposit, with the Mount Isa district hosting several other world class Pb- Zn-Ag and Cu-Au deposits, a number of which have been found in recent decades. The 1920s also saw the discovery of the high-grade deposits of the Tennant Creek Mineral Field in the Northern Territory. Gold mining commenced here in the 1930s, with copper mining commencing in the 1950s. One of the more colourful episodes in Australia’s mining and exploration history was the nickel bubble of late 1969-early 1970, with the ‘stand- out’ performer being Poseidon NL, following discovery of nickel by the company at Windarra in Western Australia. After trading at A$0.80 in September 1969, the company’s shares peaked at A$280 in February 1970, only to crash soon thereafter. The Rae Inquiry following the bubble outlined a number of improper trading practices resulting in increased regulation over the Australian share market. Western Australia remains a significant nickel producer.

The second half of the 20th century has seen exploration for all commodities and numerous discoveries, still continuing to this day. Exploration has commonly targeted historic mines, with modern mining and processing methods making what was once uneconomic or unable to be treated/mined now economically and technically viable. One feature of the early 2000s was the takeover of several of Australia’s larger miners by majors, including the takeover of North Limited by Rio Tinto in 2000, that of MIM by Xstrata (now part of Glencore) in 2003, and Western Mining Corporation by BHP-Billiton in 2005.

The Current State of Play

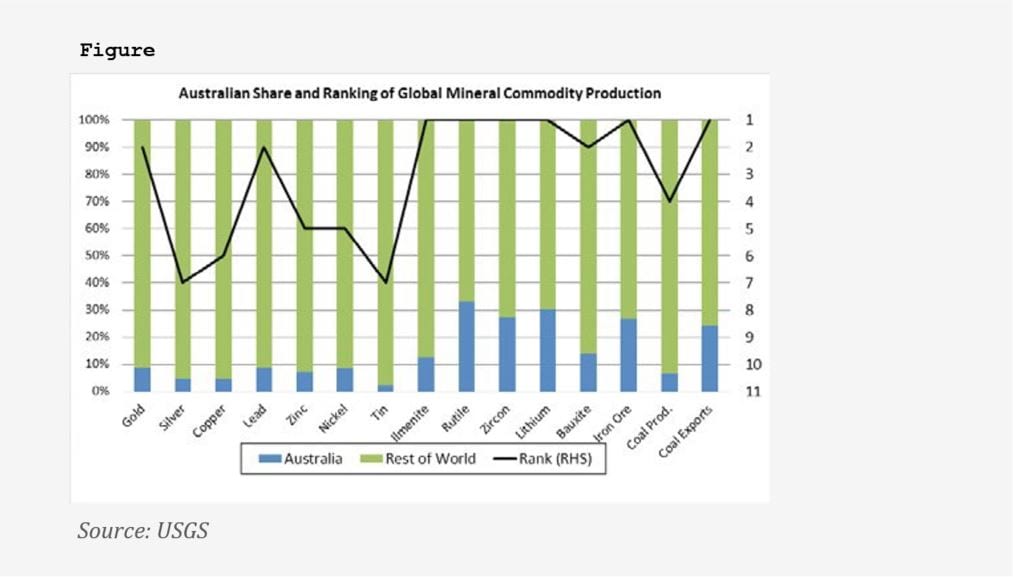

Australia is a major world producer of several commodities (Figure 1), however it is in the bulk commodities that the country is most recognised. As shown in the graph, Australia is the leading global producer of iron ore, the leading exporter of coal (although ranked 4th in terms of production), and ranked 2nd in the production of bauxite. Australia has only been a significant miner of iron ore since 1960, when the Australian Government lifted an embargo on exports (originally put in place because it was thought to be in short supply, despite the 1950s discovery of the vast Pilbara deposits). Initial mining was from South Australia, with the first Western Australian mine (Utah’s Goldsworthy operation) opening in 1965. Initial production was negligible (in the order of tens of millions of tonnes), reaching 200Mt by 2003. It currently sits at ~880Mt, with China being their main customer, succeeding Japan.

Of recent interest has been the increase in lithium production, with Australia overtaking Chile as the number one global producer due to the recent development of spoduthmene bearing pegmatite deposits in Western Australia. These were made vi- able thanks to price increases and forecast demand increases, due largely to electric vehicle uptake. Overall, minerals accounted for some 40% of Australia’s exports of A$545 billion in 2017 (and 10% of GDP), with crude petroleum and LNG providing an additional 7.4% (some tend to conveniently forget this contribution to the economy when attacking the industry). Australia was, to some extent, insulated from the worst effects of the GFC due to continuing mineral exports, as well as having a strong cash surplus.

Keeping the Dream Alive

It follows on that an active and strong exploration industry is required to maintain and grow the minerals industry, with this in Australia being reliant largely on junior and mid-cap companies. Given that the bulk of exploration is carried out by listed entities, it also follows that a suitable stock exchange is required. Ex- change services are dominated by the Australian Securities Ex- change (ASX), but there are alternative providers, the Chi-X, operating for a subset of stocks, and the National Stock Exchange (NSX), with just a handful of exploration and mining stocks. The ASX as a national market has now been around since 1987, when it was formed through the consolidation of six state-based exchanges that dated back to the 19th century.

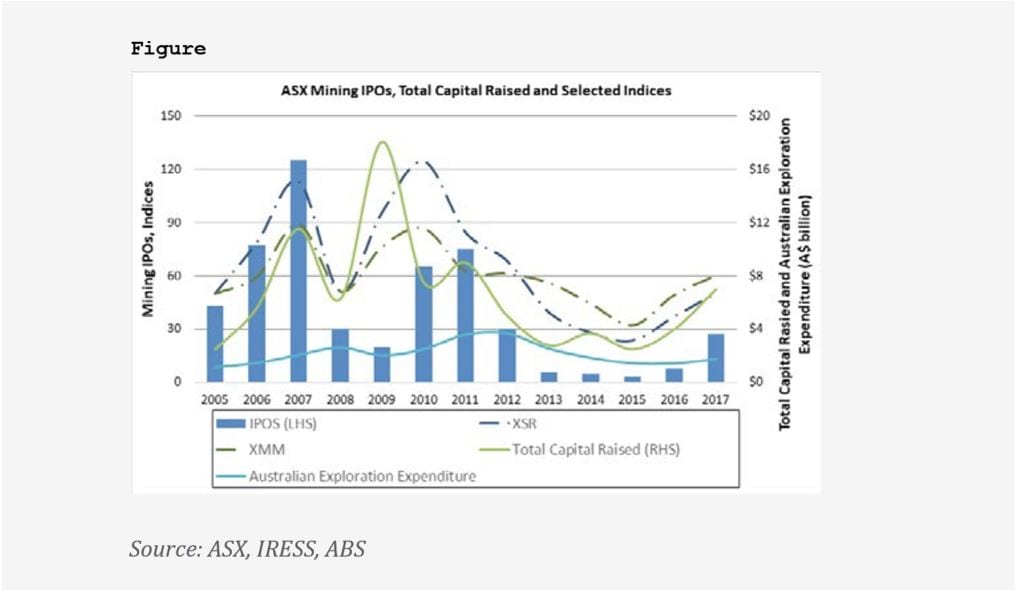

The genesis of stock exchanges was in the Victorian gold rushes in the 1850s, with each colony subsequently opening their own exchanges. Originally a mutual organisation, the ASX de-mutualised in 1998 and became a company listed on its own exchange. Unlike the TSX, which has the Venture Exchange, the ASX has only one board, with a total of 2,258 companies (capitalised at around A$1.5 trillion), of which 660 are currently in the metals and mining sector (the largest sector of the ASX), and 122 are energy explorers and producers. The ASX and the TSX are the two heavyweights for raising global mining capital, with the TSX being the leader in terms of capital raised for many years. However, that is now changing with the ASX drawing level in terms of total funds raised (and edging ahead on number of IPOs), with North American risk investors looking at other fields, including cryptocurrencies and medicinal marijuana, amongst others. Figure 2 shows the number of metals and mining IPOs, and total equity capital raised (both IPO and secondary raisings) since 2005. We have also shown indexed (to 50 in 2005) end of year values for two indices – S&P ASX 300 Metals and Mining (ASX:XMM)

and S&P Small Resources (ASX:XSR) and Australian exploration spend.

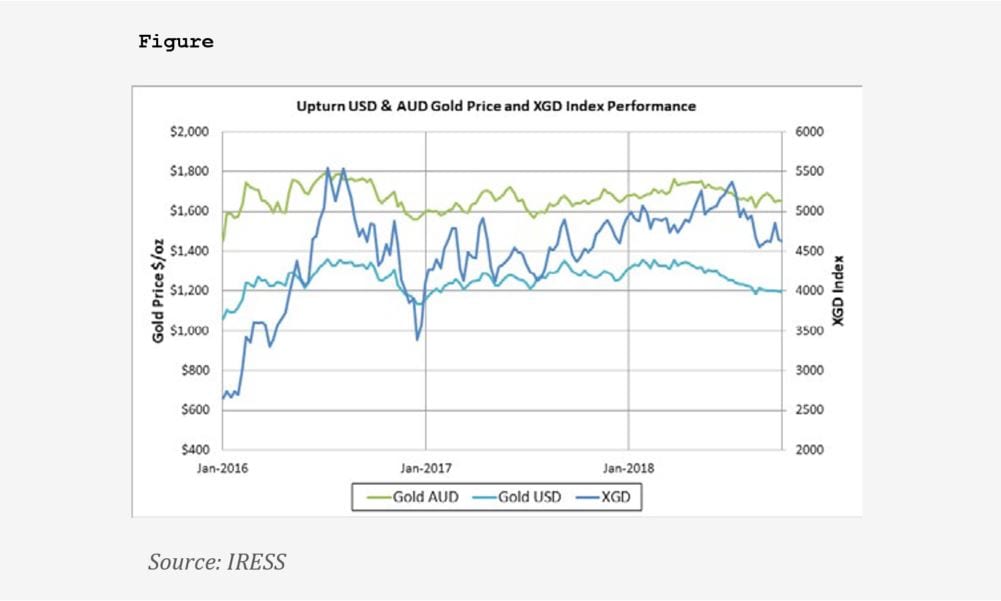

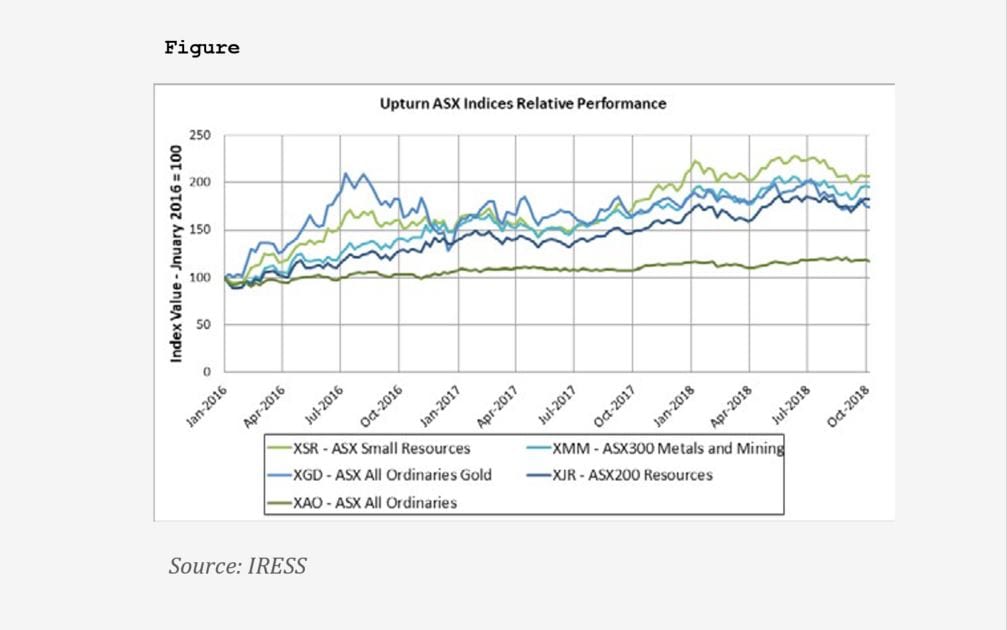

This highlights the flurry of activity during the China boom (which was interrupted by the GFC, with record raisings in 2009) and the post-boom hangover. We have now seen a resurgence since the beginning of 2016, initially driven by gold and the battery metals, particularly lithium, with investors gaining confidence after making money and seeing improving markets. Another point shown in Figure 2 is the quantum of money raised when compared with exploration expenditure within Australia. This highlights the fact that considerable money raised in Australia is spent offshore as ASX-listed companies operate in all parts of the globe. Figures 3 and 4 show the comparative performance of gold and various indices since the start of the current upturn in January 2016. The performance of gold stocks is measured by the ASX:XGD index, with Figure 3 highlighting the upturn in gold, and Figure 4 comparing the performance of various indices during the current upturn. These also include the ASX All Ordinaries Index (ASX:XAO) that measures the general health of the market. This emphasises the strong relative performance of the mining indices, albeit that they came off a very low base!

As a final point, when compared with the China boom (Figure 2), the cur- rent upturn is steady, with investors being generally more cautious after the pain post 2011, and more discriminating in what they invest in. Companies are of generally better quality, with most having ‘real’ projects, but this has started to change more recently, particularly with some very speculative, largely battery and specialty metal offerings. However, overall we are thankfully seeing less of the cowboys that were around in the 2000s.

The Australian Exploration Game

To maintain our position as a global powerhouse, Australia needs a strong exploration industry, and luckily, exploration is one thing that Australia generally does very well. As mentioned earlier, significant discoveries continue to be made in Australia, sometimes in revisiting historic mining areas and also with greenfield discoveries.

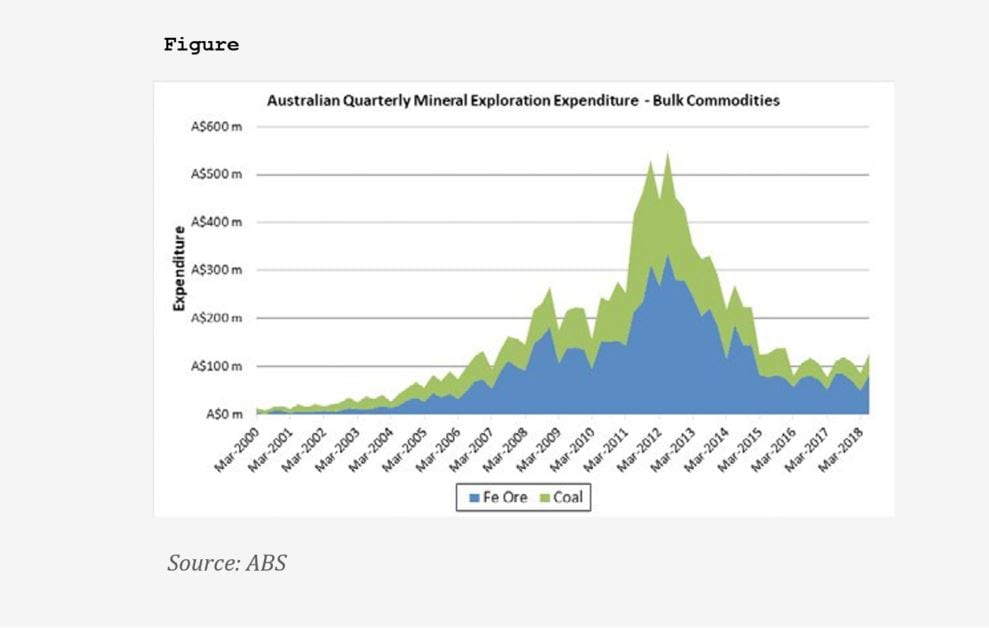

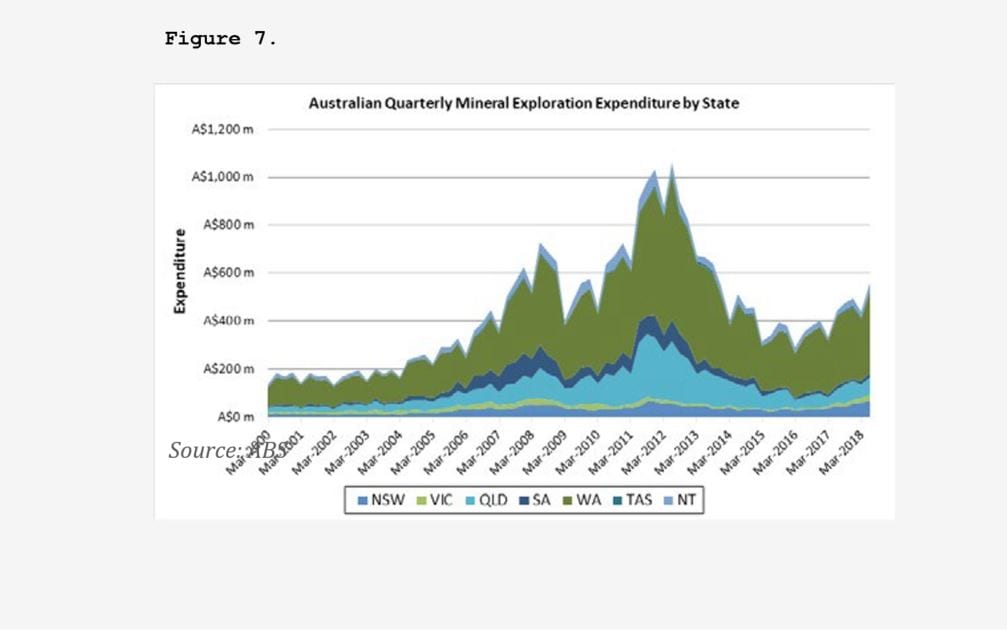

According to S&P Global Mineral Intelligence, Australia accounted for 13% of the global exploration expenditure in 2016, just behind Canada (the leading nation with 14%) and equal with the entire African continent (13%). In Australia, Western Australia was the leading state with 62%. Gold was the main target, with 57% of exploration targeting the metal. Figures 5 and 6 show quarterly Australian exploration for base, precious and other metals, and bulk commodities. These graphs highlight the cyclical nature of the industry, and also the changing targets – this is particularly noticeable in the comparative expenditure on exploration for the bulks, with these peaking in response to demand from China and consequent high prices in the early 2010s. We are now seeing non-bulk exploration expenditure heading towards peak levels (underpinned by gold), however, bulk commodity-spending remains subdued.

Another point to note is the regular variation between quarters – exploration in some parts of Australia, particularly north Queensland, Western Australia and the Northern Territory, slows or halts during the southern summer, due to the ‘wet’ and/or very hot conditions. Figure 7 shows the comparative quarterly expenditure by state, highlighting Western Australia’s pre-eminent position, followed by Queensland.

Issues Facing the Industry

All is not beer and skittles however, with the industry facing a number of challenges A key issue facing the junior explorers (and the industry as a whole) is the cyclical nature of the industry, and short-termism driving most investors, who are very reactive to changing conditions and bad news releases. Exploration is a long- term patience game, which doesn’t match the expectations of a large group of investors. In reality, the juniors, who are reliant on the investors, have no real control over this, and have to ride the waves. This can lead to panic-selling by a single investor, particularly in times of low liquidity, leading to significant falls in the share price of a company on only a minor trade. It is hard to recover the price in this situation.

However, this reactive approach also infects the majors, who are in the best position to act anti-cyclically and are not relying on investors to keep the lights on, although we consistently hear of their exploration teams being laid off in hard times. This, as well as unavoidable lay- offs from the juniors, is very damaging for the industry, in that experienced personnel leave never to return, thus leading to skills shortages when times improve. We are seeing this to some extent with the current upturn (including in-service providers), with this being exacerbated by less graduates coming into the industry. Orebodies are now also getting harder to find and require more smarts in exploration, meaning they need even more investor patience. Regulation is also getting tighter, both in the rules affecting actual operations, and on the corporate front, with activities getting tied up in more and more red and

green tape. Rules imposed by the ASX and the Australian Securities and Investment Commission (ASIC, the corporate regulator) are getting more stringent and onerous, with many in the industry thinking that some of these new regulations actually act against the interests of shareholders.

On the operations front, land access is getting more difficult, as well as companies having to jump through more and more hoops to get work programmes approved, with these approvals state-based. This leads to less efficient allocation of funds, with the time required for compliance with regulations and permitting resulting in delays in getting on the ground, and in the proportion of costs required to keep the lights on being higher. Add to this less money being put into the ground, and investors are left feeling impatient and frustrated, leading to a fall in price through selling.

But There is Some Good News

Although we see some onerous regulation, the exploration industry is well- supported by the different State Geological Surveys, with State Governments also commonly offering co-funding possibilities for exploration, particularly drilling. Also, the Federal Government has recently introduced the Junior Mineral Exploration Incentive (JMEI), which allows for company tax losses to be distributed to shareholders as a tax credit and is designed to boost investment in the exploration industry. This current scheme was setup in the 2017/2018 financial year, with credits capped at A$100 mil- lion, spread over a four-year term.

To Wrap Up

Australia, which is a resources global powerhouse, maintains a strong and skilled exploration industry, with most players listed on the ASX – one of the two key resource-focussed security exchanges globally. Although facing some headwinds, the industry remains strong, and is in a good place to maintain Australia’s pre-eminent position as a producer of a number of commodities.

As a final point, this article has provided a very short history of the Australian mining industry, mentioning a few notable events and discoveries, but there are several excellent and thoroughly readable books on the topic, including those written by historian Geoffrey Blainey. On the corporate as well as the mining side, and the shenanigans therein, there is the work by the doyen of Australian mining and financial journalism, Trevor Sykes, who, writing under the non-de-plume ‘Pierpont’, wrote the eponymously named newspaper column for many years, now available on the web.

If you can get a copy, a very humorous tome (which at times cuts close to the bone) is Sykes’ 1996 book, ‘The Official History of Blue Sky Mines’, which covers the mischievous goings-on of the fictional company, Blue Sky Mines, whose aim is to mine the market and not find a mine, with a scant regard to ethics and regulation, and even less thought for the long-suffering shareholders. I am sure some MDs and boards have used this as a training manual on how to run their companies, especially during the mid-2000’s China boom! However, rest assured that things are much better now than they were then.