Mention industrial minerals to most investors and the shutters go down pretty quickly. The markets for most are fairly opaque and can be difficult to understand. However, the mineral sands industry has been around long enough for many investors and analysts to get their minds around, and pricing and volume disclosure has improved to the extent that there is now quite clear supply/demand visibility. And the trends that are emerging should be of interest to investors. The mineral sands industry is in decline, and new mine production is desperately needed.

Mineral sand deposits consist of accumulations of economically-important minerals of relatively high-specific gravity, typically concentrated in coastal (or paleocoastal) environments. The most common economic mineral species are the titanium rich minerals, rutile and ilmenite – socalled ‘pigment feedstock’ – which are key raw materials for the production of white pigment for paints, paper and plastics, and upgraded feedstock, such as syn-rutile or high titanium slag. Zircon, typically a by-product, is an essential component for the global ceramics industry where the mineral imparts unrivalled opacity to the clay body and glazes. While there are substitutes, none are as efficient at their job as these minerals.

Much of the seaborn feedstock market is sourced from major dry-mining and dredging operations in East Africa, such as the Moma mine of Kenmare (LSE: KMR) in Mozambique, Kwale of Base Minerals (ASX:BSE) in Kenya, Fairbreeze in South Africa (Tronox, TROX US), and the largest, the Richards Bay Minerals (RBM) operation (RIO ASX and LSE) also in South Africa. All are mature operations, with the main mines of RBM in steep decline.

Environmental issues have seen the virtual shutdown of coastal operations in many parts of the world including an important recent source of supply from the beaches of Tamil Nadu in India. This alone has tightened up the ilmenite market, and prices have steadily moved from under USD 90/t (CIF) five years ago to now over USD 200/t (with pricing commonly driven by TiO2 content and ‘value-in-use’ considerations). Critical to the supply of the highest purity natural source of TiO2 (rutile) is the Sierra Rutile operation of Iluka where a decision was recently made to defer the new Sembehun project indefinitely.

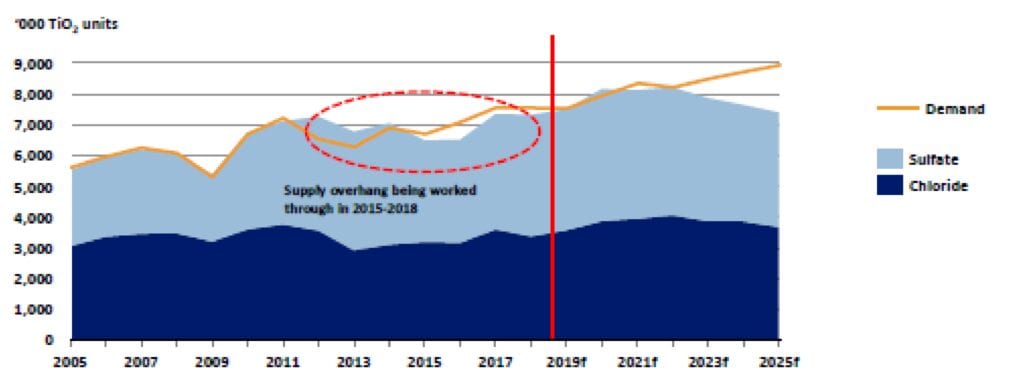

Together with mine closures (such as the Stradbroke Island operations in Queensland), industry consultant, TZMI, is forecasting an emerging deficit in TiO2 feedstock from 2021 which should be supportive of rutile and ilmenite prices.

Chinese supply of TiO2 feedstock has commonly come from ilmenite or titanomagnetite by-product of hard rock iron ore operations. Again, this is a mature industry and Chinese pigment producers are increasingly turning their attention to the seaborn market.

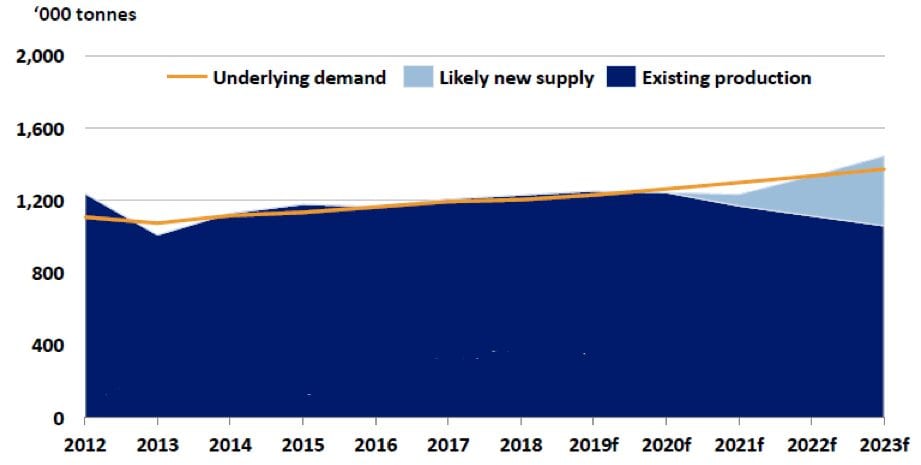

As mentioned earlier, Zircon is commonly regarded as a by-product of ilmenite and rutile production. With the exception of the Jacinth-Ambrosia deposits of Iluka (Eucla basin in South Australia) and the Grand Cote deposit of Eramet (Senegal), there are few zircon-dominated projects globally. Due to the dramatic decline in zircon production from both Richards Bay and Iluka’s Australian operations, the market has tightened up strongly. Prices have moved from under USD 1000/t in 2015 to around USD 1600/t (CIF). TZMI are forecasting a significant deficit in zircon production unless new production redresses global decline.

Zircon supply is remarkably concentrated with around 50 percent of global supply derived from three mature operations: Jacinth-Ambrosia (ca. 280ktpa, Iluka, ILU ASX), RBM (ca. 150ktpa, Rio Tinto), and Fairbreeze (ca. 170ktpa, Tronox).

In response to improving mineral sand pricing, Rio Tinto announced the go-ahead of the Zulti South Project, with the aim of “sustaining Richards Bay Minerals current capacity and extend mine life” as the grades of the North orebody decline. Construction is due to start this year, assuming all permits are obtained. First production is expected in late 2021 and is to be fully funded from internal cashflow. We had always been doubtful as to whether Rio Tinto would commit capital to RBM, even moreso when the go-ahead decision was nearly five years late. However, without Zulti South, RBM would have continued its downward value decline until mine closure in under 15 years.

The second major source of zircon production is the Jacinth-Ambrosia operations of Iluka. Here, the highest grades have passed, and Iluka is having to resort to retreatment of tailings from old operations in Western Australia to sustain long-term commitments to customers.

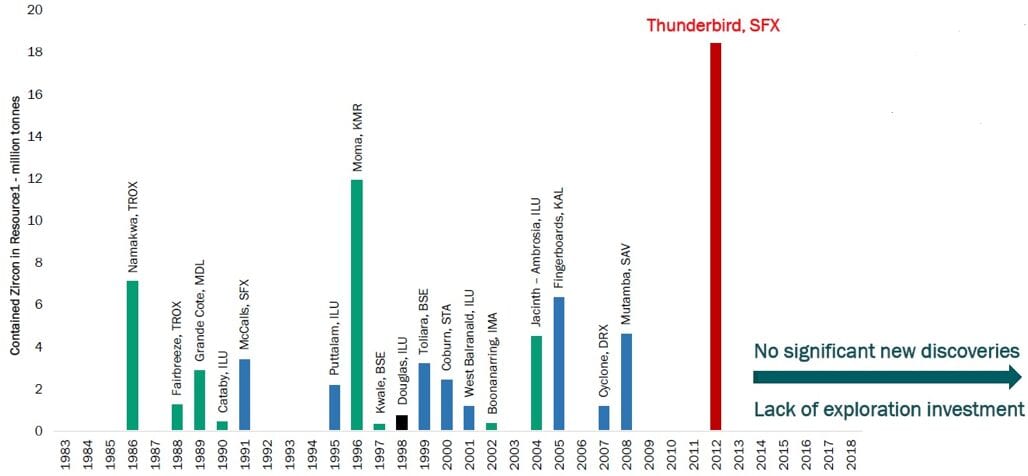

The start-up of RBM’s Zulti South mine is, in our opinion, insufficient to close the supply gap, both of zircon and TiO2 feedstock. So, where is the balance of these vital minerals to come from? As shown in the following chart, exploration has not been the answer. There has been a dearth of exploration discoveries over the past 10-20 years – partly driven by environmental constraints around the world’s coastlines.

To us, the stand-out development opportunity is the Thunderbird project located in the Kimberley region of Western Australia and 100 percent owned by Sheffield Resources (ASX:SFX). Thunderbird is a Tier 1 mineral sand project with resources of over 3 billion tonnes at 6.9% total heavy minerals (HM) with a 1 billion tonne/12.2% HM, zircon-dominated high-grade orebody. The project is fully permitted and awaits final equity funding. Production is forecast to ramp up from around 80ktpa zircon (plus zircon in concentrate) in Stage 1 to a peak of around 200kt in Stage 2. By-product ilmenite is to be sold to Chinese pigment producers. First production is likely in 2021-22.

A second, high quality, zircon-rich project is Fingerboards, a Victoria project 100 percent owned by unlisted Kalbar Resources. Once permitted (final permitting is now on critical path for the project), Fingerboards is forecast to produce some 120ktpa of zircon in concentrate, together with by-product ilmenite and monazite (for the rare earth market). Without clarity on permitting, a start date is uncertain, but is likely to be two to three years away. Kalbar is proposing to sell all of its heavy mineral product in the form of a gravity concentrate to a rapidly growing refining industry in China and Southeast Asia.

There are several promising TiO2-dominated projects on the drawing board, including RBM’s Zulti South. The most advanced projects of any significance, none of which are close to construction, include the Chibuto project in Mozambique (with production levels suggested to be ca. 500ktpa TiO2 units per year, owned by Chinese interests), Puttalum (370ktpa in Sri Lanka, Iluka), the Sembehun rutile project (80ktpa, Sierra Leone, rutile dominated, Iluka, with its DFS currently under review), Tolliara (400ktpa in Madagascar, Base Resources), and the Dundas project in Greenland (150ktpa, Bluejay Mining (AIM:JAY), although the latter might be limited by environmental issues. Most of these projects contain low levels of zircon – a historically valuable by-product.

Few of these new feedstock projects are located in what we would classify as “tier 1” geopolitical destinations. For this reason, attention has refocused on the very large, low-grade deposits that what is known as the Wimmera deposits within the Murray Basin of Victoria. These were discovered in the 1960s and 70s but have generally been regarded as sub-economic due to low-grades, metallurgical challenges, and poor ilmenite quality. The two most advanced projects, Donald (approximately 110-120ktpa TiO2 units) and Avonbank (perhaps 110ktpa) are controlled by Chinese interests, but there is little in the public domain regarding the status of these projects. Mineral sands major Iluka controls the WIM100 deposit in the Basin, and feasibility work has commenced on the project.

To us, the Wimmera deposits look to be a very long-term source of significant tonnages of TiO2 feedstock, and commodity prices seem likely to remain relatively high to incentivise production from these projects. Delays are inevitable as the companies deal with a highly rigorous permitting regime in Victoria. We are not expecting to see development activity in the Wimmera for at least three to four years.