The last quarter of 2018 proved to be tumultuous for just about every asset class traded on an exchange. An explosion of volatility and violent moves in global equity indices instilled fear to all investors and caught many hedge funds and professional traders on the wrong side. The reasons for this kind of unpredictable behaviour are being attributed mainly to worries over Chinese economic growth and by extension to its impact on the world, as well as trade disputes initiated by US President Trump. A change rhetoric by the US Federal Reserve about the trajectory of interest rates also confirmed worries over the level of global debt and the massive fiscal deficits that prevail in the developed economies.

In times of short-term instability, it can be useful to take a step back and think of the longer-term context. The facts point to global debt-to-GDP ratio reaching over 320% in 2018 as emerging economies, in particular, more than doubled their debt levels since the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2008. Any corporate entity would be under enormous pressure to reduce that kind of leverage especially when its growth appeared to be slowing and profit margins were squeezed.

The massive liquidity injections by central banks around the world in response to the risk of financial melt-down after 2008 promoted not only the massive accumulation of debt but the rapid inflation of asset values as too much cash was chasing higher returns in an environment of low interest rates. Debt was, to a large extent, transferred from private hands, primarily banks, to state control. The credit risk of states is perceived to be much lower simply because a state can print money and control the monetary base far longer than any private entity with limited capital. The central bankers’ strategy seemed to work over the next decade, albeit at a slower pace of growth than anticipated. When they realized, ultimately, that this kind of leverage could back-fire and cause several bubbles to burst, they started to unwind and pull-back liquidity. Emerging markets felt the strain immediately and the biggest of them all, China, got worried.

Gold, the traditional safe-haven asset, had seen its price race up to $1,927 per ounce in 2011, as investors were terrified by the central banks’ experiment and sought safe-havens in the aftermath of the GFC. Since that high in 2011, however, it seemed that everyone thought that the global economy was on a steady track of growth out of the debt problem. It took another seven years to realize all is not well. America’s deficit has ballooned and President Trump’s tax cuts are making it worse. Populism has risen across the US and Europe, causing unexpected moves such as Brexit and instability in Italy and France, two of the largest economies in the Eurozone. Most economists would agree that the massive accumulation of debt by state institutions cannot carry on forever, not without serious repercussions on the economy. Most importantly, private sector debt is very sensitive to changes in interest rates and exchange rate parities. Any attempt to unwind indebtedness by either state or private parties is set to cause an increase in volatility in those asset classes that are funded with leverage.

As markets went into a tail-spin in the last quarter of 2018, gold started to regain strength testing the psychologically important level of US$1,300 per ounce. According to the data published by the World Gold Council, gold-backed ETFs increased their holdings in each month of the last quarter. Furthermore, the central banks of China, Russia, Hungary and Poland were big buyers of bullion in an apparent move to diversify their reserves out of volatile currencies. Weakness in economic growth would be the catalyst for further correction in equity valuations as earnings expectations decline, and bonds would not offer any shelter as higher interest rate expectations keep their values in check. The safe-haven attribute of gold is coming back in investors’ minds and, as global allocations in gold are very low, the rebalancing can push its price to new highs.

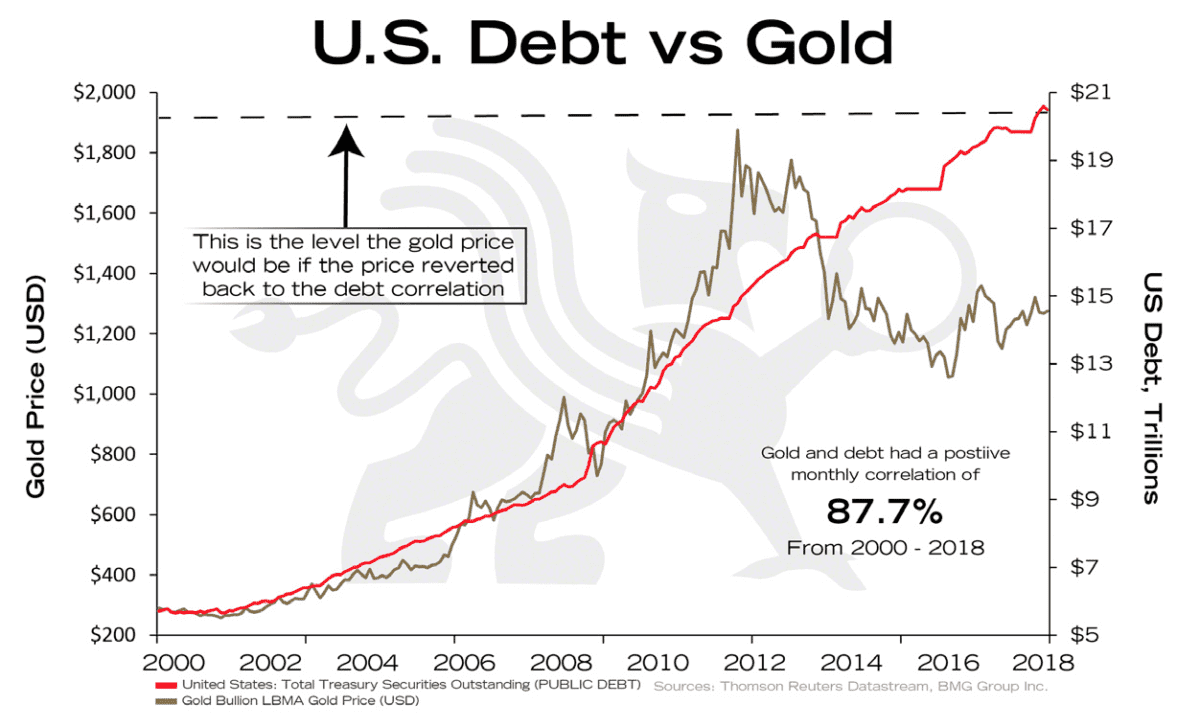

As the chart plotting the price of gold compared to the size of US debt demonstrates, the historical correlation of the two was broken in 2011 as investors were lulled into a false-sense of security by the actions of central banks and favoured risky assets to gold. Reversion to the mean points not only to the unsustainable level of state debt, but also to the potential appreciation in the value of gold. A rising gold price would also cause shares of gold miners to rerate as their earnings prospects would increase rapidly. Those of smaller miners would rise even faster due to their higher operational exposure. I believe that any well thought-through portfolio should have a meaningful allocation to gold and gold mining equities in today’s environment.